Asian Services in Action health center helps immigrants, refugees get vaccinated

While overall COVID-19 vaccination rates for Asian-Americans are relatively high in Ohio, Asian-American and Pacific Island (AAPI) refugees and immigrants in Northeast Ohio—many who don’t speak English—have had to negotiate unique cultural and language barriers on the road to getting vaccinated.

Elaine Tso, CEO of Asian Services in Action (ASIA), a social services agency based in Cleveland and Akron, said that outside of the former mass vaccine site at the Wolstein Center in Cleveland, most vaccine sites don’t have interpreters on hand to help those who don’t speak English. Nor do the websites for vaccine registration have versions in the languages or dialects that many of Tso’s clients speak.

Dr. Amy F. Lee, ASIA, Inc.’s current board president, got her vaccine at the ASIA’s International Community Health Center in Akron earlier this year.“It’s a harder-to-reach community, and there’s been some challenge with vaccine uptake and general access to the vaccine through spaces where they don’t have language access to guide them through the process,” Tso says.

Dr. Amy F. Lee, ASIA, Inc.’s current board president, got her vaccine at the ASIA’s International Community Health Center in Akron earlier this year.“It’s a harder-to-reach community, and there’s been some challenge with vaccine uptake and general access to the vaccine through spaces where they don’t have language access to guide them through the process,” Tso says.

Plus, some of these immigrants and refugees can’t afford Internet access or aren’t sure how to operate computers, Tso says, meaning it can be difficult to sign up for a vaccine, or get the most accurate info about the vaccine.

To try to combat these headwinds Tso says ASIA has been hosting vaccine clinics twice a week at its International Community Health Center in Akron since March. She called it a trusted site for many in the AAPI community; plus, it’s a federally qualified health center (FQHC)—a clinic with a sliding-scale pay model that primarily serves low-income patients.

“It’s much easier to go somewhere where they're familiar with the environment and it’s not overwhelming compared to going to a mass vaccination site,” Tso says.

Brant T. Lee, a professor of law at the University of Akron, got his vaccine at the International Community Health Center in Akron, and is a board member with ASIA. He explains that there’s also a fair amount of hesitancy to getting the vaccine among AAPI immigrants and refugees.

“It’s based on an unfamiliarity with and not necessarily a huge amount of trust in formal lines of communication,” Lee explains. “Some people come from countries where the government is not as benign. So, they might not trust those official sources of information as much. But they also may not have seen (that information) also, just heard rumors or whatever.”

Tso says the vaccine clinics at the Akron Health Center have been successful at reaching that community, with over 90% of the vaccine doses going to AAPI immigrants and refugees.

While ASIA lacks the capacity to do weekly vaccine clinics at its health center in Cleveland, Susan Wong, chief program officer for ASIA, said ASIA had been organizing small groups of people—10 or 15 at a time who speak the same language—to go to the Wolstein Center. That way, she says, they could make sure those groups have transportation and somebody who can speak at least some English to guide them through the vaccination site.

Meanwhile, there were 18 translators who spoke six different languages physically present at the Wolstein Center, plus a mobile computer screen which allowed staff to bring up interpreters from elsewhere, says Ohio Department of Health spokesperson Alicia Shoults.

ASIA also organized a pop-up vaccination site with the Cleveland Department of Public Health at Cove City Church in Cleveland’s AsiaTown, where 300 people were vaccinated in April.

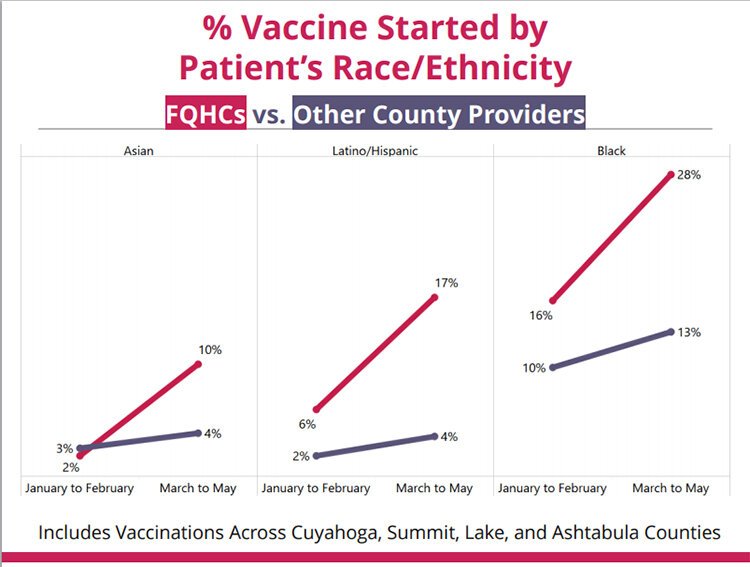

Chris Mundorf, director of data analytics with the Better Health Partnership, says a much higher percentage of vaccines are being given to people of color at FQHCs like ASIA, compared to other vaccine sites in Cuyahoga County.

“Each FQHC has developed innovative strategies, informed by data, to better reach underserved populations including developing partnerships with the faith-based community, health departments, and others; ensuring high-touch patient outreach; and offering translation services at the CSU Wolstein mass vaccination event to boost access to vaccines,” Mundorf said in an email.

However, FQHCs have only given out about 4% of all vaccines in Cuyahoga County, Mundorf says, and Tso estimates ASIA has only directly vaccinated around 1,000 people across both of its sites. Kate Warren, research fellow with the Center for Community Solutions, says she believes that chronic underfunding of community health centers like ASIA has led to a “weaker pandemic response in vulnerable communities.”

Graphic provided by Better Health Partnership

Graphic provided by Better Health Partnership

“The FQHCs have done incredible work with their limited resources, but if the overall health and social services system were stronger, we would have been in a better position for pandemic response and vaccination,” she says.

Even still, ASIA is responsible for the vaccinations of about 10% of the Asian population in Summit County, Mundorf says, which Tso said she regards as a success.

Wong and Tso say part of that success in reaching the immigrant and refugee community is through direct outreach—done through phone calls, texts and, messaging apps—along with handing out fliers at ethnic grocery stores.

Tso explains that ASIA can do that kind of outreach to so many different groups of people because, as an organization, it can provide interpretation in about 55 different languages and dialects and has 28 staff who are either bilingual or multilingual.

Still, Wong says it can be slow going, with culturally appropriate outreach strategies needed for each group of people in their own language. For example, Wong says ASIA uses the Chinese app WeChat to disseminate information to a group of several hundred Chinese people in Cleveland.

“We just need to do it step by step,” she says.

Lee, the University of Akron professor, says he believes ASIA is positioned to be a trusted voice on the vaccine, considering it’s a social services agency that people already are familiar with. He said providing those services in a “culturally competent” way—in the language that people speak—was one of the reasons ASIA was founded.

“There were Chinese residents in Cleveland who were taking a bus to New York City to see a doctor who spoke their language,” he explains. “There was a particular dialect of Chinese that’s not common around here.”

So far, it looks like ASIA may have helped bolster relatively high rates of vaccination among AAPI residents in general in Cuyahoga and Summit counties, with 64.20% of the Asian population in Cuyahoga County and 54.68% of the Asian population in Summit County having received their first doses as of June 3.

These percentages are both higher than the overall vaccination rate in each county across all races (49.74% in Summit, 50.84% in Cuyahoga). In general, vaccination rates for Asian-Americans seem to be higher across the country, compared to other races.

But Tso cautions that there’s still plenty of work left to do; vaccination rates have slowed in Ohio in recent weeks. “The provider might want to administer the vaccine on the spot, however, once a vial of vaccines has been ‘opened’ then we need nine other arms to vaccinate during the limited number of hours before the remaining vaccines in that vial will be ‘wasted,’” Tso said in an email.

Tso says there aren’t any easy answers, but she says ASIA is committed to working through these issues.

This story is sponsored by the Northeast Ohio Solutions Journalism Collaborative, which is composed of 20-plus Northeast Ohio news outlets including FreshWater Cleveland.