Baldwin Water Treatment Plant: A wonder and a workhorse

Despite sitting on the coast of Lake Erie and the Cuyahoga Delta’s many tributaries, clean drinking water was not necessarily easy to access in the 1800s. In the early days, Cleveland’s settlers in the east side Heights area, which sits about 800 feet above sea level atop the Euclid Bluestone terrace, had springs and wells for drinking water.

But the lower elevations—or three-quarters of the city’s population—were in areas with poor water quality or access. Water from Lake Erie was considered unsafe to drink.

In 1852 the City of Cleveland hired hydraulics engineer and architect Theodore Scowden to design a public water works system, which was subsequently built between 1854 and 1856.

Cleveland Water was established in 1856 to ensure everyone had access to clean and safe drinking water. In 1885, the 80-million-gallon, open-air Fairmount Reservoir and pump station were completed on the Euclid Terrace at what is today Fairhill/Martin King Jr. Drive and Stokes Boulevard, while the Kinsman Reservoir was built on the Berea Sandstone Terrace in Mt. Pleasant (about 920 feet above sea level), providing clean drinking water to most of the east side.

As the city’s population grew in the early 20th Century, the need for larger reservoirs and pump stations became apparent. The 135-million-gallon Baldwin Reservoir and pump station were completed in 1925—at the time the largest reservoir in the world.

The Fairmount pumping station was built before the Baldwin Reservoir, ca. 1890Today, Palladian style Baldwin Filtration Plant and Reservoir still ranks as one of the largest covered reservoirs in the world, measuring 551 feet wide 1,035 feet long, and 39 feet deep. Before the reservoir was filled, the interior had a cathedral-like appearance. The reservoir was so large and stunning that residents toured it before it was filled. The 750-foot-long filtration building was carved out of solid rock.

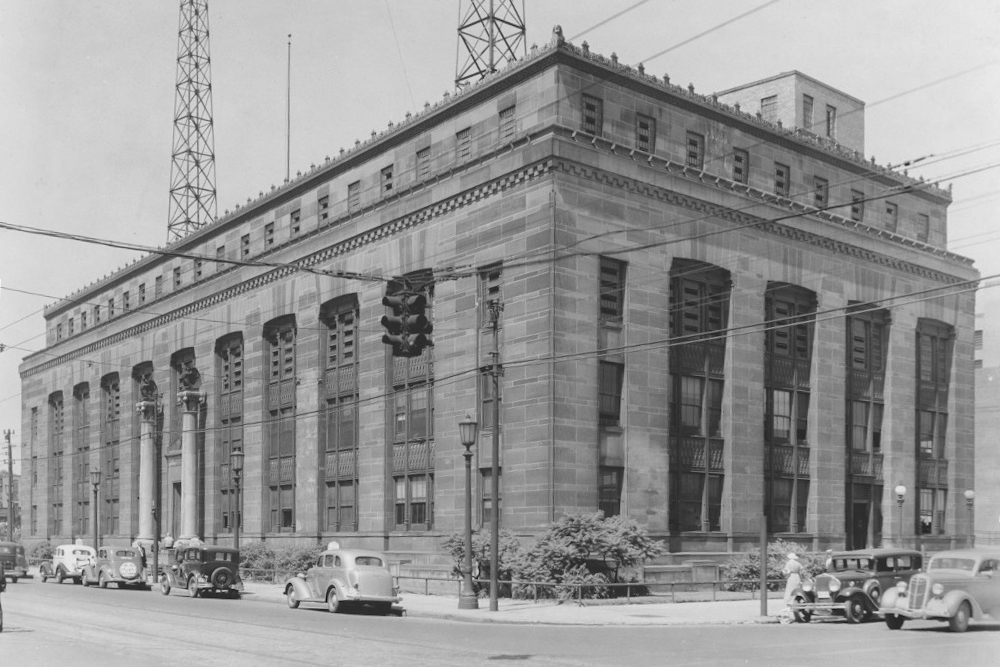

The Baldwin facility was designed by Cleveland architect Herman Kregelius, who in 1933 designed the Gothic-style Parma Reservoir. He worked as an architect in the early 1900s before becoming the City of Cleveland architect in the 1920s. During his tenure, Kregelius designed the Central Police Station on Payne Avenue and the Cleveland Fire Department #28 on Carnegie Avenue in 1925 (today the Western Reserve Fire Museum and Education Center), among other projects.

Accents on the brick facility that sits above ground include wrought iron arched windows, doors, and rails; brass entry doors; and a large bell that once warned boaters of Cleveland Water’s intake 5-Mile Crib on Lake Erie.

The reservoir is covered by a thin concrete slab that is supported by nearly 2,000 30-inch columns. Grass covers the reservoir roof, providing a park-like setting on 14 acres. The property was designed by landscape architect Albert Taylor, a Massachusetts native who used both formal and informal principles of European landscape design in his residential, institutional, and public projects.

Taylor is also known for designing additions to Lake View Cemetery in the 1930s, developing Ambler Park from the Baldwin plant to Coventry Road, and retaining walls along Cedar Glen that runs adjacent to Doan Brook in Cleveland Heights. In 1931, he drafted plans for the completion of the Mall and a development plan for Forest Hills Park. Taylor went on to be the landscape architect for the Pentagon.

The Baldwin facility has endured several updates in its 98-year history, including a $156 million renovations as part of Cleveland Water’s Plant Enhancement Program between 2001 and 2012.

Today, Baldwin pumps an average of 70 million gallons of water a day to residents and businesses located downtown, the east side of Cleveland, and the eastern and southeastern suburbs.

Cleveland Masterworks is sponsored by the Cleveland Restoration Society, celebrating 50 years of preserving Cleveland’s landmarks and cultural heritage. Cleveland Restoration Society preserves houses through the Heritage Home Program. Experience history by taking a journey on Cleveland’s African American Civil Rights Trail.Become a member today!

Cleveland Masterworks is sponsored by the Cleveland Restoration Society, celebrating 50 years of preserving Cleveland’s landmarks and cultural heritage. Cleveland Restoration Society preserves houses through the Heritage Home Program. Experience history by taking a journey on Cleveland’s African American Civil Rights Trail.Become a member today!