Preserving our cultural heritage: Cleveland Restoration Society gets $50,000 planning grant

The Cleveland Restoration Society (CRS) announced last week that it received $50,000 from the African American Cultural Heritage Action Fund (AACHAF) to support a planning study to create a brick-and-mortar fund for historic Black churches in Cleveland.

CRS was one of only 33 organizations nationwide, out of 672 applicants, to receive funds from AACHAF, which is a program of the National Trust for Historic Preservation, says Anne Doten, CRS director of development.

“We’re very excited to get this award,” she says. “A study will help us determine what steps we need to take.”

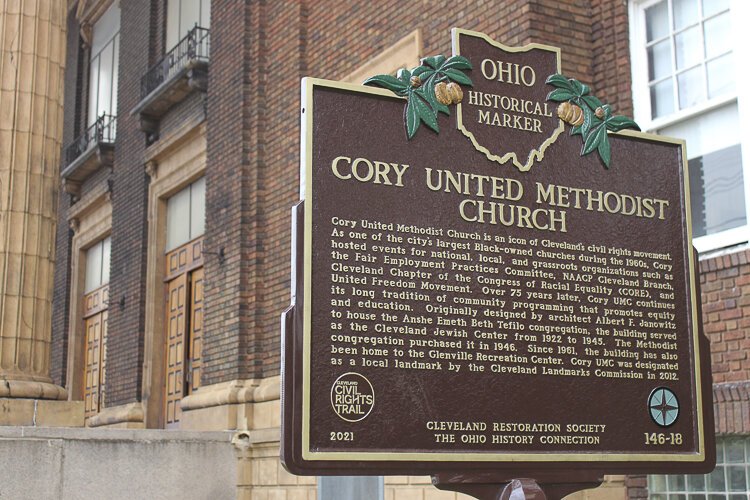

Cory United Methodist ChurchBlack churches in Cleveland and the North in general have played a key role in the spiritual, political, social, and economic cohesion of African Americans in the U.S.

Cory United Methodist ChurchBlack churches in Cleveland and the North in general have played a key role in the spiritual, political, social, and economic cohesion of African Americans in the U.S.

Many of the buildings themselves are notable not only for their architecture, but for their role in the Civil Rights struggle. They served as a platform for the abolitionist movement leading up to the Civil War and Emancipation, a supportive framework for African Americans during the years of the Great Migration, and a strong influence on the Civil Rights movement in the 1950s and 1960s.

Doten says the study will be led by the national consulting firm Compass Group to identify and interview community members, current and perspective donors, and community leaders to determine how the funds should be used.

“We definitely want community buy-in, and we definitely want feedback,” Doten says, adding that the study should take about a year to complete.

She explains that preserving Cleveland landmarks is critical because they illustrate a colorful cultural history of the city. Many of the historically Black churches in the city were actually built as by white church congregations or as synagogues before coming predominantly Black churches.

For instance, what stands today as Cory United Methodist Church in Glenville, which was the largest Black church in the city during the 1950s and 60s and hosted Civil Rights leaders like Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., W. E. B. Du Bois, and Thurgood Marshall, was originally built as Anshe Emeth Beth Tefilo Congregation in 1920. Anshe Emeth In 1946 sold the building to Cory Methodist before it moved to Cleveland Heights as Park Synagogue.

"Black churches in Cleveland are woefully undercapitalized, and many lack the resources needed to repair and maintain their structures," says Doten. "Our goal is to help preserve these churches and the African American cultural heritage that they encapsulate."

In addition to hosting national and local Civil Rights leaders, Doten says many of Cleveland’s Black churches asl have a strong history of serving the community’s needs—from encouraging congregation members to vote to serving as resource centers for food pantries, vaccination sites, or school supplies.

“It’s not just the architecture it’s the history of these places,” says Doten.