First three historical marker sites chosen for the African American Civil Rights Trail

After two years of planning, applying for, and receiving grant money, the Cleveland Restoration Society (CRS) is beginning to move forward with its plan for the African American Civil Rights Trail in Cleveland.

On Monday, Feb. 22 officials at the Cleveland Restoration Society (CRS) announced the first three locations for the eventual 10 historical markers that will memorialize locations associated with Cleveland’s struggle for Civil Rights between 1954 and 1976.

In October 2019, CRS was awarded a $50,000 African American Civil Rights Grant from the

National Park Service for its project “In Their Footsteps: Developing an African American Civil Rights Trail.” to preserve and highlight stories related to the African-American struggle for racial equality in the 20th century.The first three sites chosen are Cory United Methodist Church at 117 E. 105th St.; Glenville High School at 650 E. 113th St.; and an undecided location in the Hough neighborhood.

The sites were chosen based on a survey conducted last August to gather public input on a list of 20 possible locations. CRS then formed a committee made up of its trustees, business leaders, and three “crucial thinkers” that include Thomas L. Bynum, director and associate professor of history; professor Donna McIntyre White—both with Cleveland State University’s Black studies department—and James Robenalt, an attorney with Thompson Hine and author of “Ballots and Bullets: Black Power Politics and Urban Guerrilla Warfare in 1968 Cleveland.”

“For the first three sites, the biggest influence was a combination of the survey results and the known history of the sites,” says Margaret Lann, director of preservation services and publications for CRS. “A couple of other sites received high marks on the survey, but they need more research or a little more work on where the marker will go.”

Additionally, Lann says the committee liked the proximity of the first three sites—with Hough and Glenville being adjacent neighborhoods. She says the markers are meant to go into underrepresented Cleveland neighborhoods.

“The markers recognize there’s a whole community of people that history has not properly reported on,” she says. “The goal is to have more of these markers in underrepresented communities.”

ABC News5 story on CRS' first three Civil Rights Trail choices.

CRS breaks down the significance of each of the three sites:

Cory United Methodist Church

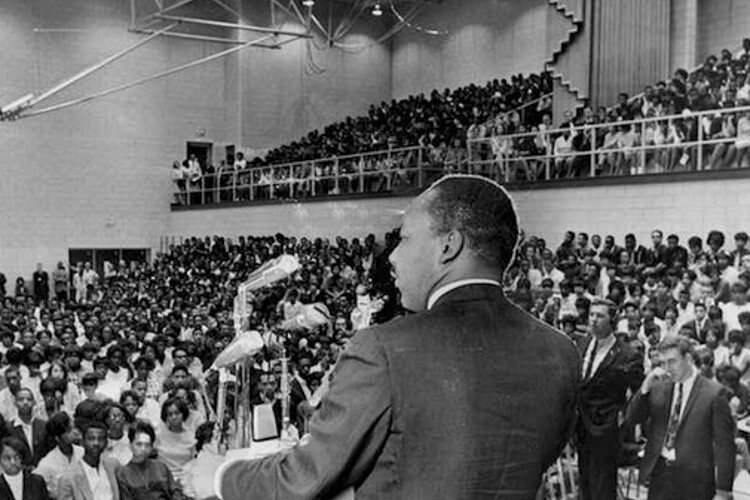

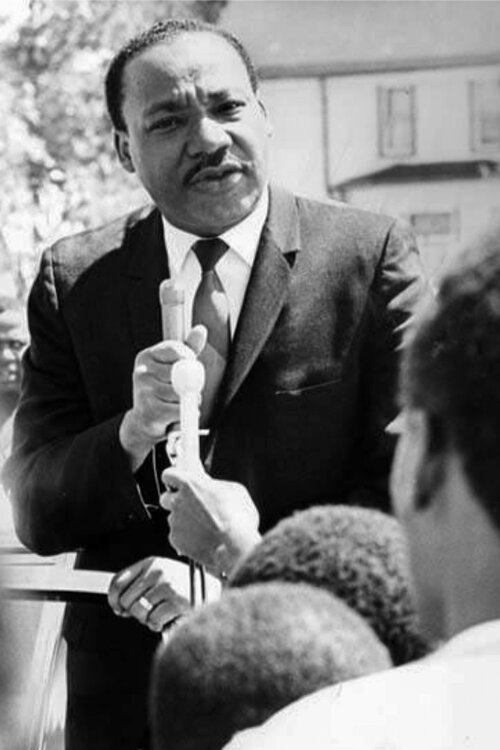

According to researchers and scholars, Cory United Methodist Church was the largest Black church in the city during the 1950s and 60s. Through the many services the church provided, it became a key venue for organizing and a key platform for influential civil rights leaders to speak to predominately Black listeners. W. E. B. Du Bois (1950) and Thurgood Marshall (1951) addressed the congregation from the pulpit. Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. spoke there many times.

An estimated 5,000 people packed the sanctuary and streets outside Cory during a visit by Dr. King on May 14, 1963. The Cleveland chapter of the Congress of Racial Equality brought Black author Louis Lomax and Malcolm X to speak on April 3, 1964.

It was then that the Muslim minister and human rights activist delivered the first iteration of his speech, titled “The Ballot or the Bullet.” Cory also played an instrumental role on the grassroots level, holding election campaign rallies, voter education, and registration drives. Established in Cleveland in 1963, the United Freedom Movement (UFM) held many meetings at Cory. The UFM fought for education, employment, health, housing, and voting rights. Rev. Sumpter Riley was a top leader with the organization.

Many of the historic events acknowledged by these markers show the power and unity of the communities they are in—and the works the people who live in Glenville and Hough are doing today.

These markers will highlight that positive work. For instance, Lann says Cory was responsible for creating a family credit union in 1958, when the Black community couldn’t get financing, and in the 1970s opened a food bank. “The church is still doing these things in the community today,” she says.

Hough

The Hough Uprising occurred in the summer of 1966. It is said to have been the result of a dispute in a café at East 79th Street and Hough Avenue. Whatever the case, days of vandalism, looting, arson, and gun violence, stemming from years of racial tension and discrimination against black residents, resulted. Hough was selected because the event is considered the most significant urban uprising in Cleveland, in reaction to substandard housing, criminal injustice, and the lack of public accommodation. Five days of violence ended with four people dead, 50 injured, and 275 arrested. The event made a lasting impact on the city.

Lann says the uprising occurred as frustrations mounted over unfair housing practices and discrimination. “Businesses and many houses were owned by white landlords that didn’t live there, and a lot of people who live there were fighting the unfair practices,” Lann explains. “The events leading to the uprising left a massive impression, and they have shaped unkind memories or perceptions of that neighborhood.”

Glenville High School

The CRS African American Civil Rights Trail Committee chose Glenville High School as one of the trail sites because of its location and the uniqueness of the speech given to high school students by Dr. Martin Luther King in 1967.

In 2012, a Glenville High School teacher was cleaning out a closet and found a recording of Dr. King’s speech to the students. He targeted his message at young people and their ability to participate in non-violent, social change.

“The community responded to the message because it was one of the few times King’s speech was solely directed at young people in Cleveland,” says Lann. “He urged them to get involved, he talked to them about voting and getting civically involved—urging the students to take action.”

All three of these sites mark the history and signs of positive change. “Part of the trail will be getting people there to witness what [positive] changes are going on. We can relate many of these events to current events today,” Lann continues. “The Civil Rights fight continues, and we want to draw that conclusion.”

This marker site location presents an opportunity to speak directly to the next generation. And it recognizes a time when Cleveland youth were engaging in a new movement. That movement resonates today, Lann says, with the current racial tensions and a new generation of activists. “In the Black Lives Matter movement, young people are very involved in copying that,” she says.

There is also great relevance in the speech, delivered on the verge of the city electing its first Black mayor, Carl Stokes. Further, the committee realized a strong correlation between the message of Dr. King and the Black Lives Matter movement of today, and its young leaders.

Lann says the process of choosing and installing all 10 markers on the Civil Rights Trail will be slow. “You can only apply to have three to four manufactured a year,” she explains of the markers. “Hopefully, we can start putting markers in the ground. Of course, this will be staggered, but we hope to start by this fall.”

Once CRS does get started in placing the markers, Lann says she wants to keep the trail going. “There’s nothing to say we can’t expand the trail,” she says. “In my mind it won’t end with 10—it’s really just a start.”