Greater harm than good: HB 276 passed the Ohio House, but it could endanger LGBTQ+ Ohioans

Courtesy of Buckeye Flame

Courtesy of Buckeye Flame

As one anti-LGBTQ+ Ohio bill has a hearing this week and another made national headlines without even been assigned a committee, a third piece of legislation set to disproportionately harm LGBTQ+ people quietly passed the Ohio House of Representatives recently.

On March 30, House Bill 276—dubbed the “prohibit receiving proceeds of prostitution bill"—passed by a vote of 87 to four, banning any individual from receiving or acquiring money or any other thing of value if “they know that it was earned from sexual activity for hire.”

Because LGBTQ+ people are more than twice as likely to engage in sex work as members of the general population, experts say they’re doubly vulnerable to the bill’s unintended consequences. This could leave sex workers unable to buy things like groceries and diapers, while also criminalizing their sources of support, be they family assisting with childcare, landlord, convenience store owner, or even a health care provider.

The bill’s sponsors, Reps. Jena Powell (R-Arcanum) and Jean Schmidt (R-Loveland), say that HB 276 was introduced to “make it easier for law enforcement and prosecutors to tie traffickers and pimps to illegal activity and return convictions for these heinous crimes.”

But neither the word “pimp” nor any reference to human trafficking appear in the text of HB 276, and advocates fear the bill’s vague language will allow law enforcement to further marginalize and target trusted loved ones in the lives of LGBTQ+ sex workers—like family members or small children who depend on their financial support.

‘Overly broad with unintended consequences’

Because HB 276 prevents individuals from “receiving or acquiring money,” earned via sex work, the bill could prevent sex workers from spending money on basic needs, from rent and childcare to food and healthcare costs.

Emily Dunlap, a senior staff attorney at Advocating Opportunity—an Ohio-based nonprofit law firm providing free legal services for trafficked and exploited persons—says bills like HB 276 can leave sex workers even more vulnerable to violence, food insecurity, and housing instability.

“If sex workers and trafficking victims are not allowed to spend money—which is effectively what HB 276 does by making it a felony to receive money from them—it gets much more difficult for individuals to survive or to seek help if they are being exploited,” says Dunlap.

Further, an individual found to have received funds or goods from individuals engaged in sex work may also be charged with second or third-degree felonies, punishable by up to eight years in prison and a $15,000 fine—which could devastate already vulnerable families and important support networks.

“Maybe this is a grandmother who is helping take care of their kids or buying groceries,” says Sarah Inskeep, Ohio state policy & movement building director for URGE, a nonprofit focused on building young people power for reproductive justice. “The real problematic part with this bill is that it is targeting and criminalizing every facet of a sex worker’s life: a friend, their family, a car driver, a landlord, a healthcare provider.”

Inskeep says that while HB 276 may address human trafficking on the surface, the bill’s language is consistent with previous Republican legislative approaches to outlaw certain behaviors with which they disagree or politically or personally.

“I think their idea of ‘protecting and saving’ is law enforcement, jailing folks, and notching up penalties and fines as a way to try and discipline people out of behaviors that don’t fit [these representatives’] moral codes,” says Inskeep. “This punitive approach has caused greater harm than good.”

How will HB 276 affect LGBTQ+ Ohioans?

With a sizable number of LGBTQ+ individuals engaged in sex work, HB 276 has the potential to disrupt the health and safety of a large number of LGBTQ+ Ohioans.

According to the U.S. Transgender Survey (2015) conducted by the National Center for Trans Equality:

- About 12% of LGBTQ+ people said they’ve engaged in sex work to earn income (vs. roughly 6% of the total U.S. population).

- 19% of respondents participated in sex work for money, food, a place to sleep, or other goods or services.

- Nearly half (45%) of respondents who have done income-based sex work were currently living in poverty.

Additionally, all of these percentages increased dramatically for Black respondents:

- 27% of Black respondents participated in sex work for money, food, a place to sleep, or other goods and services (vs. 19% overall).

- 21% of Black respondents participated in sex work for income (vs. 12% overall).

- Of those who did sex work for income in the past year, Black transgender women represent nearly two-thirds (65%).

Though HB 276 does not mention the LGBTQ+ community, the queer demographic landscape of sex work means the ramifications of the bill would disproportionately affect LGBTQ+ Ohioans.

“This is very much LGBTQ+ issue,” says Inskeep. “A lot of folks who are otherwise marginalized because of lack of employment and other social net services, end up selling sex and then are criminalized for doing so.”

Just four Ohio representatives opposed the bill

Rep. Mary Lightbody (D-Westerville) voiced her support for measures to curb human trafficking, but said that HB 276 would overreach that goal, ultimately voting against the bill.

“I voted against House Bill 276 because I am concerned that the bill is overly broad and is likely to have unintended consequences,” Lightbody told "The Buckeye Flame" in a written statement.

Lightbody also pointed to testimony from a representative from the Office of the Ohio Public Defender that “existing law sufficiently cover all illegal aspects of prostitution,” and that criminalizing the receipt of money that is a result of human trafficking may unintentionally affect unrelated individuals, like landlords, convenience store owners, or healthcare providers.

Rep. Michael Skindell (D-Lakewood) also voted against the bill, saying he too felt the bill was “excessive.”

“A family member, whether a spouse, child, or parent who receives money for food or clothes, a hotel or convenient store clerk, a friend or landlord could receive jail time or steep fines,” Skindell says. “The legislation will further the exploitation of individuals in the sex trade.”

Consensual sex work is not human trafficking

Though HB 276 has been described by sponsors and media coverage solely as an anti-trafficking measure, advocates say the bill is a result of a ubiquitous conflation of human trafficking and sex work.

So advocates across the state are encouraging Ohioans to learn more about the difference between human trafficking—which, again, appears nowhere in HB 276’s text—and sex work, which appears in language throughout the bill.

“We need to have honest, non-stigmatizing conversations about what human trafficking vs. sex work looks like and that not everyone who is selling sex is doing so in a way that is forced or coerced,” says Dunlap.

“We can’t pass laws making people in the sex trade more vulnerable and more marginalized and expect it to help them,” Dunlap adds. “And that is what is happening right now with HB 276. While we should all be doing our best to end human trafficking, bills like HB 276 that only focus on increased criminalization while ignoring the needs of victims, workers, and already marginalized individuals, are not an effective way to accomplish this goal.”

With advocates projecting the harm that HB 276 poses to LGBTQ+ Ohioans, individuals can reach out to members of the Senate Judiciary Committee to voice their concerns.

“I hope people contact their representatives, letting committee members and their Senators know that this law—while stated that it has good intentions—is extraordinarily harmful and is a massive overreach of its alleged objectives,” Dunlap says.

As the language of the bill has been couched solely in terms of hampering human trafficking, speaking out against HB 276 may be perceived as opposing legislation meant to curb sexual exploitation—an especially complicated situation for Ohioans as the state was ranked among the worst in the nation for human trafficking in 2020.

Ultimately, though the intent behind HB 276 may have been to protect the vulnerable, the reality may be that it targets more communities than it protects.

“Criminalizing every aspect of sex worker’s life is not going to help set people up for success to exit the trade in any meaningful way,” Inskeep says. “If anything, HB 276 could push them further into it.”

Additional reporting by H.L. Comeriato.

This article was originally published on May 18 in The Buckeye Flame, a FreshWater's partner in the Northeast Ohio Solutions Journalism Collaborative (NEO SoJo). Republished with permission.

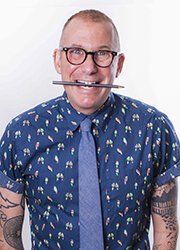

About the Author: Ken Schneck

Ken Schneck is the Editor of The Buckeye Flame, Ohio’s LGBTQ+ news and views digital platform. He is the author of Seriously…What Am I Doing Here? The Adventures of a Wondering and Wandering Gay Jew (2017), LGBTQ Cleveland (2018), LGBTQ Columbus (2019), and LGBTQ Cincinnati. For 10 years, he was the host of This Show is So Gay, the nationally-syndicated radio show. In his spare time, he is a Professor of Education at Baldwin Wallace University, teaching courses in ethical leadership, antiracism, and how individuals can work with communities to make just and meaningful change.