Is housing market recovery leaving Cleveland’s East Side behind?

More than a decade after the housing market crash, parts of Cleveland and Cuyahoga County may be finally climbing out of the hole, says Western Reserve Land Conservancy senior policy advisor Frank Ford. But other parts—in particular, Cleveland's East Side and the eastern inner suburbs—still have a long way to go to address the blight and ruin that have brought down many neighborhoods, he says.

“The good news is, we have had upward momentum for at least four years,” he says. “We should celebrate. But policy makers and elected officials [need to recognize] there are communities that are struggling.”

Ford has published his research on the housing market recovery every July for the past four years. His latest report, “Housing Market Recovery in Cuyahoga County: Will Cleveland’s East Side Be Left Behind?,” cites the areas that have recovered but also notes those that still need work—and funding—to fully recover.

“It’s as if a tsunami wave came off of Lake Erie and hit the East Side of Cleveland and inner ring suburbs,” says Ford. “The wave has receded, but we’re left with the damage.”

Federal, state and county funds earmarked for blight recovery are estimated to run out by 2020. The Western Reserve Land Conservancy has raised more than $450 million and created 57 land banks throughout Ohio to combat the blight left from abandoned and foreclosed homes, says vice president Jim Rokakis, a former Cuyahoga County treasurer.

In Cuyahoga County, primarily Cleveland and the inner ring suburbs, $80,592,000 was received and spent, Rokakis says. Additionally, Cleveland Mayor Frank Jackson earmarked $14 million for recovery efforts.

The money, spent on demolishing or rehabbing blighted houses, has helped raise property values and hopes in neighborhoods like Glenville, Fairfax, and Buckeye, Rokakis says.

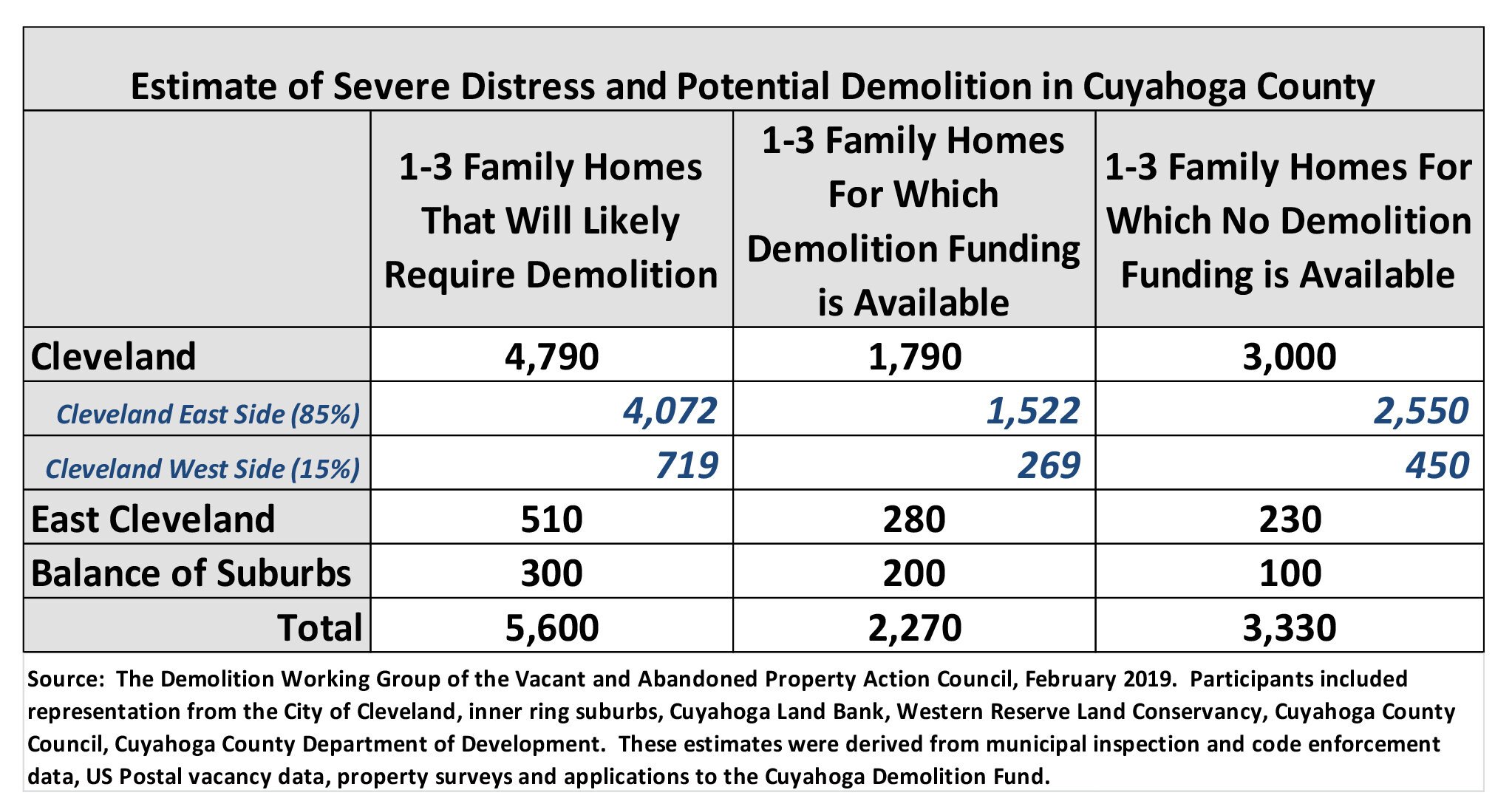

At the height of the crisis, in 2007 and 2008, estimates projected 12,000 to 14,000 blighted properties in the region required demolition. Around 2014, the conservancy began tracking blight, and Ford estimated in 2015 that 7,279 properties required demolition.

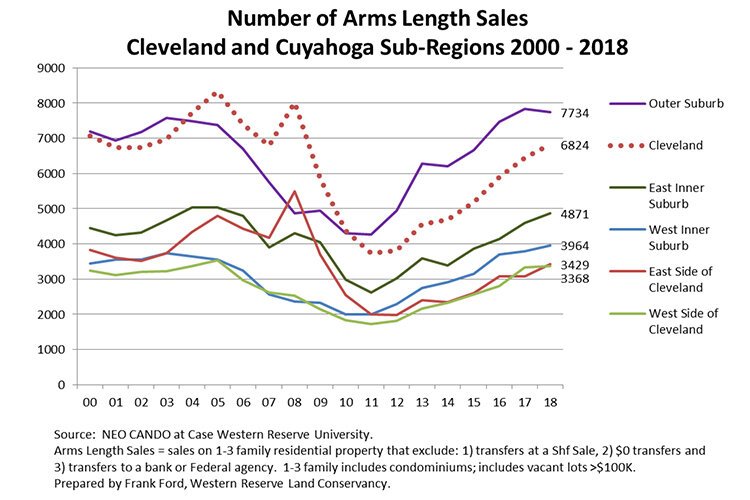

While blight has decreased and median home prices have increased steadily since Ford published his first report in 2016, Cleveland's East Side has only recovered 34% of its median home prices before the crash, his latest report says.

However, Ford reports that Cleveland’s West Side has seen a 79% recovery, compared with the eastern inner suburbs at 64%. He also finds that five eastern inner suburbs rank at the bottom of the spectrum: Euclid, Garfield Heights, Warrensville Heights, Maple Heights, and East Cleveland. The range goes from East Cleveland at only 34% recovery (mirroring the recovery of east side Cleveland neighborhoods) to the other four communities seeing 50% to 60% recovery.

“The good news is that all of these communities are on an upward trajectory,” says Ford. “But the degree of recovery varies.”

Both Ford and Rokakis point out that the eastern Cleveland neighborhoods were hit particularly hard by the crisis because of a higher concentration of poor, African-American residents who were especially victimized by predatory lending practices.

“It’s the biggest criminal conspiracy in history in this country,” says Rokakis. “Eighteen percent of Cleveland’s population was lost between 2000 and 2010, and the vast majority of that was because of the foreclosure crisis.”

Although the numbers continue to improve, Ford reports that in February 2019, the Land Bank still had 3,300 blighted properties in Cuyahoga County, including 3,000 in Cleveland, of which 2,500 are on the East Side. And the Land Bank is at capacity and cannot accept any more properties, he says.

Rokakis estimates the number of blighted properties to be a bit higher—at around 4,000 properties in Cleveland—and another 1,000 in the inner eastern suburbs.

While both men give credit to the Cuyahoga County Land Bank for its efforts in acquiring vacant, blighted properties and either renovating or demolishing them, when recovery funding runs out next year, there will still be work to do.

The aftermath looms. “There will be no money to address them, and 75 percent of the homes are on the East Side,” Ford says. “Recovery is on the way, but now we’re threatened that there’s no money to finish the job.”

Both Ford and Rokakis are doing their best to keep the recovery momentum going. “Everybody who is interested in the health of the Cuyahoga County real estate market should do whatever they can,” says Ford, adding that Rokakis has been working tirelessly with federal officials and has connected with Ohio Gov. Mike DeWine and Ohio House District 16 Rep. Dave Greenspan of Westlake on securing additional funding.

Greenspan is championing House Bill 252 to allocate an additional $150 million for blight removal in the state budget.

“There’s no answer yet, but he’s probing different answers,” says Ford of Rokakis. “Jim is the one person leading the effort to try to raise new funding at the state level and with the federal government. However, locally, I would hope that both the city of Cleveland and Cuyahoga County would consider renewing their commitments for blight removal funding when funds run out in 2020.”

Rokakis says he hopes federal blight relief funds allocated to Mississippi and Alabama will be reassigned to states like Ohio at the end of this year, since those states have not yet used the money.

And, despite the need for additional funding, Rokakis does say Ohio—and Cleveland—should be proud of the work officials have accomplished in blight removal this far. “This is the most forceful response in the country,” he says of the efforts. “The work we have done here has served as a beacon to other communities. But we have a long way to go.”