Presentation to highlight unique history behind Lee-Harvard neighborhood

As Cleveland’s eastern suburbs were just beginning to establish themselves in the 1920s, Cleveland’s Lee-Harvard neighborhood, bordering Shaker Heights, Warrensville Heights and Maple Heights on the the city’s south east side, was thriving in its own right.

The Lee-Harvard neighborhood, once known as Miles Heights Village and the Lee-Seville neighborhoods, was historically an integrated community of notable firsts. Ohio’s first African-American mayor, Arthur Johnston was elected in 1929 when the neighborhood was mostly white. His house on East 147th Street still stands today.

The neighborhood established many of the first citizen's councils and neighborhood associations in the region and had an interracial police force.

On Thursday, October 6, the Cleveland Restoration Society (CRS), along with Cleveland Ward 1 councilman Terrell Pruitt, the Harvard Community Services Center and CSU’s Maxine Levin Goodman College of Urban Affairs, will present “Cleveland’s Suburb in the City: The Development and Growth of Lee-Harvard.”

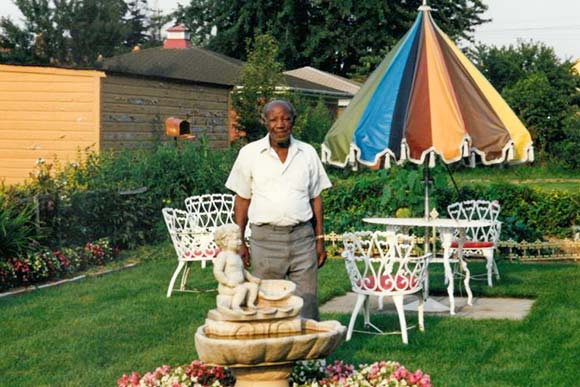

Coley Family--1964The free discussion will be led by Todd Michney, assistant professor at the University of Toledo and author of Changing Neighborhoods: Black Upward Mobility in Cleveland, 1900-1980.

Coley Family--1964The free discussion will be led by Todd Michney, assistant professor at the University of Toledo and author of Changing Neighborhoods: Black Upward Mobility in Cleveland, 1900-1980.

“We at CRS have been so impressed with the neighborhoods of Ward 1, Lee-Harvard and Lee-Seville,” says Michael Fleenor, CRS director of preservation services, "because they reflect our recent history – Cleveland’s last expansion, progress in Civil Rights, and the growth of neighborhood associations and community development corporations in the late 20th Century."

In 1932, Miles Heights was officially annexed as part of Cleveland, but the neighborhood remained a popular choice to settle for African-Americans who were looking to move to the suburbs. Many residents moved to Lee-Harvard from the Central, Glenville and Mount Pleasant neighborhoods.

“It was an integrated community so early,” explains Fleenor. “During World War II the neighborhood served as temporary housing for returning soldiers because it was already integrated and many families came by train from the south and other parts.”

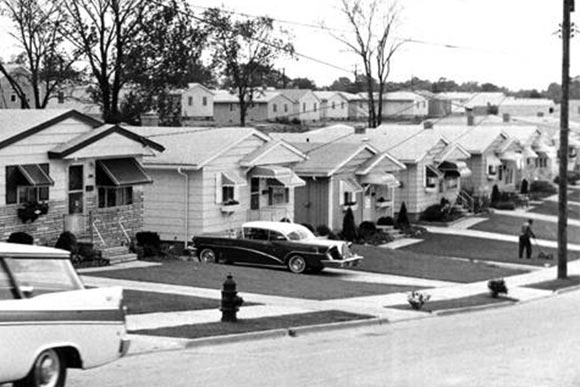

In the 1950s and 60s, the neighborhood really caught its stride, with modest brick homes going up all over the area. “A lot of the people who live there have been there for 50 years,” says Fleenor. “It’s been very stable. It’s a middle class neighborhood.”

Arthur Bussey, an African-American builder, began building the mid-century brick homes in 1949 on Highview Drive and Myrtle Avenue, off of Lee Road just south of Miles Road, and continued building until the late 60s. Bussey targeted African-Americans and designed the modest homes to be attractive to higher-income buyers.

The homes built during this period are all well maintained today, and many of the original residents are still living there or they are leaving them to their children. Fleenor also predicts that the neighborhood is potentially attractive to Millennials thinking about buying homes.

“Perhaps there’s an opportunity because the houses aren’t huge – about 1,200 to 1,500 square feet,” Fleenor says. “There’s an opportunity for young people who are struggling now and open to smaller houses. There’s a great opportunity to build on the rich history.”

Fleenor also notes that the Lee-Harvard neighborhood has plenty of greenspace and parks.

Early on, the north end of the neighborhood was made up mostly of Eastern European and Italian families, so there was a large catholic concentration that transitioned as the neighborhood became African American.

Throughout the years and changes, churches have played a prominent role in the area.

The former St. Henry Church parish at 18200 Harvard Ave. opened in 1952, with a convent and school added in 1954 and an administrative building added in 1959. After experiencing financial difficulties in 1969 the church closed the convent, which then became the Harvard Community Services Center.

Archbishop Lyke School, took over St. Henry’s school before St. Henry’s merged with other area Catholic churches in 2008 and relocated to 4341 East 131st St. The rectory was recently for sale.

What is now Whitney Young Middle School was formerly Hoban Dominican High School for Girls.

Advent Evangelical Lutheran Church was organized in 1962.* The congregation bought a beer market with a bad reputation in the neighborhood and converted it to a church before hiring a prominent African American architecture firm to design a contemporary building in 1965. The Lutheran Church of the Good Shepherd was built in 1945.

*CORRECTION: On May 5, 2017, Fresh Water received a communication from Rev. Dr. Leonard Killings, Pastor, Advent Evangelical Lutheran Church that said, "Advent's founder is indisputably an African Descent person and it was founded by African Descent persons."

The original reporting stated that the church was founded by a white minister. Fresh Water apologizes for the confusion.

John F. Kennedy High School was built in 1966.

The Lee-Harvard Shopping Center, built in 1949, became the first African American owned and managed shopping center in the country in 1972. Neighborhood residents bought the center when they noticed the property and surrounding area declining.

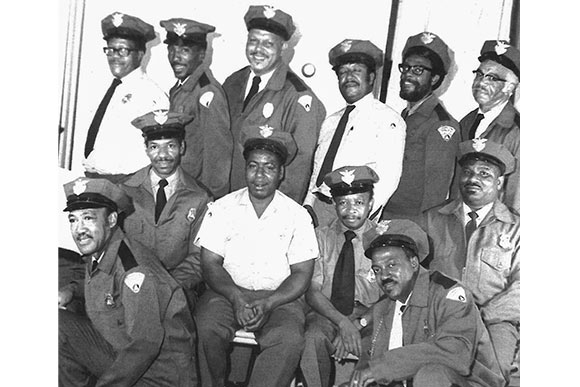

Also in the 70s, a group of residents formed an auxiliary police force to help patrol the neighborhood. The force operated out of small building on a used car lot. A taxi service donated two cars for patrol, while ladies in the community would provide coffee and pastries for the officers.

The auxiliary police would hold costume parties on Halloween and bicycle rodeos for the community. “The kids got to know the police officers and the officers got to know the kids,” explains Fleenor. “It was so successful, they got federal funding to increase officers in the neighborhood.”

Such community involvement and pride is what has kept the Lee-Harvard area steady over the years. “Lee-Harvard has one of the first community development corporations in Cleveland,” says Fleenor. “There are very few abandoned properties, and if there’s one property abandoned it’s the talk of the town.”

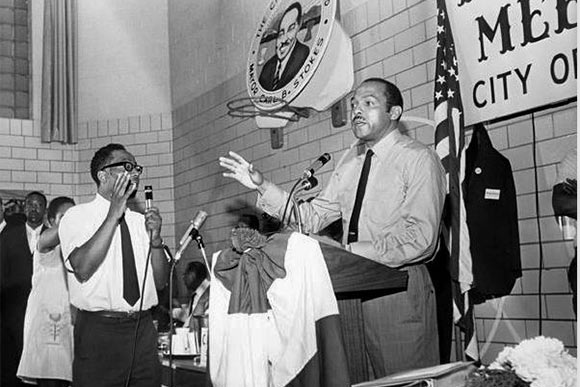

While Carl Stokes was mayor of Cleveland, residents lobbied in Columbus to keep liquor licenses out of the neighborhood. “It shows how politically active they were,” Fleenor says. “Then they fought Mayor Stokes to keep public housing out and Mayor Stokes called them “black bigots.’ They didn’t want to jeopardize the middle class lifestyle.”

“Cleveland’s Suburb in the City” will be held at the Levin College of Urban Affairs, 1717 Euclid Ave., from 4 to 6 p.m. this Thursday. Click here to register. The program is part of the Levin College Forum.