Richman Brothers: Known for its quality clothing, stellar treatment of employees

On the west side of East 55th Street near Lake Erie at the north end of the street stands a large derelict factory building. To see it now, it is hard to believe that it once housed one of Cleveland’s most successful businesses.

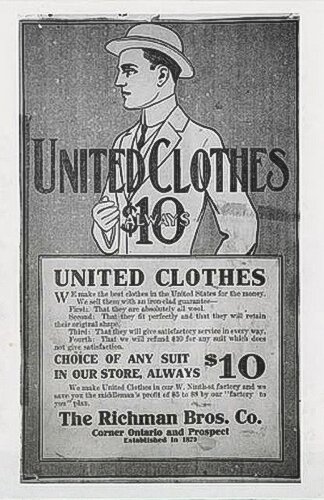

Advertisement for Richman Bros. Co. 1920sBuilt in 1917, it was headquarters for Richman Brothers, a manufacturer of high-quality men’s clothing for more than 100 years. Progressive management at the company provided unheard of employee benefits—such as interest-free loans and paid vacation for hourly workers.

Advertisement for Richman Bros. Co. 1920sBuilt in 1917, it was headquarters for Richman Brothers, a manufacturer of high-quality men’s clothing for more than 100 years. Progressive management at the company provided unheard of employee benefits—such as interest-free loans and paid vacation for hourly workers.

Management’s sense of duty to the community was such that when the building was completed it was immediately made available to serve as a hospital to provide care for wounded soldiers from the First World War.

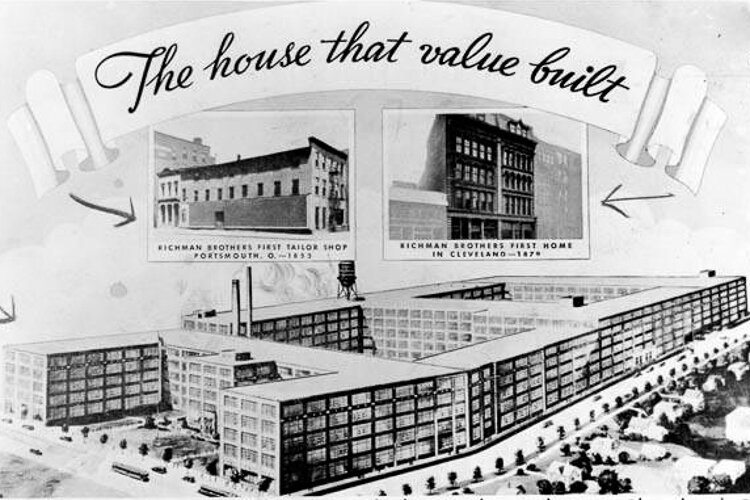

The story began in Portsmouth Ohio when Bavarian immigrants Henry Richman Sr. and his brother-in-law Joseph Lehman founded Lehman-Richman Co. in 1853. Seeking wider opportunity, they relocated to Cleveland in 1879. By 1904 the name was changed to Richman Brothers as Harry Richman’s three sons had by then taken over the business.

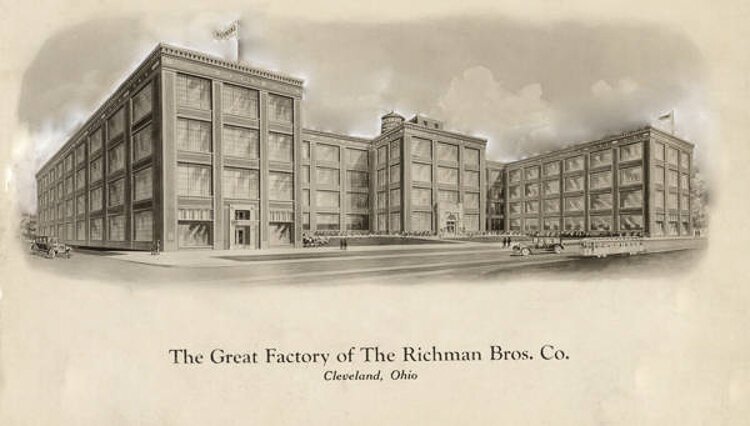

Almost 40 years after the move to Cleveland, Richman Brothers opened its first purpose-built factory, built specifically to manufacture clothing, consolidating its manufacturing operations under one roof at 1600 E. 55th St.

The new building was designed by the firm Christian, Schwartzenburg and Gaede (today Neville Architects in Beachwood), the Gaede in this case representing Oscar Gaede, the father of Robert C. Gaede, one of Cleveland’s most influential late 20th Century architects.

The factory was greeted with great acclaim, with the Cleveland Chamber of Commerce declaring it the “Best Built Factory of 1917.”

The Richman Brothers Building 2014

The Richman Brothers Building 2014

Subsequent additions in the 1920s enlarged the structure to its present size of 650,000 square feet— with 17 acres under one roof. The new building provided working conditions that were previously unheard of in the garment industry. Fifteen-foot-high windows provided an abundance of natural light, and the 60-foot-long cutting tables were the largest in the industry.

Employees were treated with courtesy and consideration. In addition to two weeks of paid vacation—one week at Christmas and one week during the Fourth of July—Richman Brothers offered paid maternity leave, a 36-hour work week when 48-hour weeks were common, and pensions after 15 years of service. The company also offered stock options, held company picnics at Euclid Beach Park, and in 1949 added a third week of paid vacation.

Workers stitching garments at Richman Brothers factory in 1927The employees never unionized because of their employer’s considerate treatment.

Workers stitching garments at Richman Brothers factory in 1927The employees never unionized because of their employer’s considerate treatment.

The Richman Brothers rapport with their employees was so strong that it is said they could stand at the front door and greet each employee by name as he or she arrived. This involved personal knowledge of each of the 2,000 employees.

Nathan Richman was the last survivor of the original three brothers. He was held in such high regard that upon his death in 1941, 2,000 Richman Brothers employees attended his funeral.

The business continued to grow and expand for decades thereafter, and a new suit from Richman Brothers for weddings and graduations was a rite of passage for generations of young men from the Cleveland area.

Remaining independent for more than a century, Richman Brothers merged with the F.W. Woolworth Company in 1969. By the mid-1970s, there were hundreds of Richman Brothers stores across 39 states.

Twenty years later, Woolworth began to divest itself of lesser performing subsidiaries. Richman Brothers was deemed to one of those companies and ceased to exist by 1992—a sad end for what was once one of Cleveland’s great business success stories.

The building was listed in 2012 on the National Register of Historic Places. Today it stands empty, deserted for 30 years, and now listed as a redevelopment opportunity with a $3.5 million asking price many deem too high to attract developers.

Overall, a very sad end for the story of something once regarded as a Cleveland showplace.

Remember, all glory is fleeting.

About the Author: Tom Matowitz

Recently retired after a 37-year career teaching public speaking, Tom Matowitz has had a lifelong interest in local and regional history. Working as a freelance author for the past 20 years he has written a number of books and articles about Cleveland’s past. He has a particular interest in the area’s rich architectural history.