Frances Payne Bolton: Nursing advocate, Congresswoman, Franchester Estate owner

A child of privilege who chose not to live like one, Frances Payne Bolton worked tirelessly to advance the cause of nursing and in long service in the U.S. House of Representatives.

Frances Payne Bolton, 1957Born in Cleveland in 1885 as Frances Payne Bingham, she was related by blood and marriage to several of Cleveland’s most influential 19th Century families. Her father, Charles W. Bingham, was classically educated at Yale and a strong promoter of education and the arts. He was involved in a range of local business and cultural activities, including serving as a trustee of Lakeside Hospital, the Western Reserve Historical Society and the Cleveland Museum of Art. Bingham was also a member of the Old Stone Church in Public Square from 1862 until his death in 1929.

Frances Payne Bolton, 1957Born in Cleveland in 1885 as Frances Payne Bingham, she was related by blood and marriage to several of Cleveland’s most influential 19th Century families. Her father, Charles W. Bingham, was classically educated at Yale and a strong promoter of education and the arts. He was involved in a range of local business and cultural activities, including serving as a trustee of Lakeside Hospital, the Western Reserve Historical Society and the Cleveland Museum of Art. Bingham was also a member of the Old Stone Church in Public Square from 1862 until his death in 1929.

Bingham instilled a sense of social responsibility in his children early in their lives. For instance, after reviewing Frances’ accounting for her allowance, he pointed out that while her arithmetic was correct, he was disappointed to see she had spent the entire sum on herself. A lifelong lesson was instilled.

Bolton’s early life was not without tragedy. Her mother died when she was 12, followed by her beloved brother, Charles, just three years later.

She was educated at Hathaway Brown and Miss Spence’s School (today the Spence School) in New York City, as well as in her father’s library, whose books she read voraciously.

In 1907 she married Chester Castle Bolton, a childhood friend and a graduate of University School and Harvard University. The Boltons were destined to have four children—three boys and a girl, who died in infancy.

In 1917 Bolton’s life changed irrevocably. Her uncle Oliver Hazard Payne died, leaving her an immense personal fortune. After serving as a Union army officer in the Civil War Payne returned to Cleveland to open an oil refinery.

Payne sold the refinery property to John D. Rockefeller’s Standard Oil company in 1872—a transaction that made him wealthy beyond his wildest dreams.

Philanthropy became a large part of Bolton’s life, particularly her conviction that nursing should be elevated to the status of a profession. As a very young woman she was directly involved in nursing, accompanying nurses to poverty-stricken homes in Cleveland where the need for their care was great.

Frances Payne Bolton School of NursingBolton never forgot this experience, and her generosity was such that the nursing school of Western Reserve University was named in her honor in 1935—becoming Case Western Reserve University’s Frances Payne Bolton School of Nursing.

Frances Payne Bolton School of NursingBolton never forgot this experience, and her generosity was such that the nursing school of Western Reserve University was named in her honor in 1935—becoming Case Western Reserve University’s Frances Payne Bolton School of Nursing.

Bolton’s husband, Chester, had become active in politics and government, starting with his service as an army officer in Washington D.C. during World War I. A republican, he served in both state and national government by the early 1930s.

His opposition to policies of Franklin D. Roosevelt’s New Deal cost him his seat representing Ohio’s 22nd Congressional District in the House of Representatives but he regained it early in 1939. This return to government was short lived. He died unexpectedly in October 1939, leading to another turning point in Bolton’s life.

About to turn 55, she resolved to complete her husband’s unfinished term in Congress. Bolton won the seat in her own right in 1940, beginning a career in government that would last nearly 30 years.

Bolton rose to positions of responsibility quickly, promoting her interests in nursing and international affairs. She is responsible for the 1943 Bolton Act, which created the U. S. Cadet Nurse Corps, which trained nurses and committed them to a tour of duty. Bolton successfully argued that the Corps must include Black women. In just its first year the Corps trained more than 124,000 nurses.

In fact, Bolton was an ardent supporter of Civil Rights, voting for Civil Rights bills as early as 1957, firmly convinced it was the right thing to do.

She traveled extensively during the war, seeing with her own eyes the impact of the war in Europe.

Bolton was on good terms with U.S. Presidents—from Franklin Roosevelt to Lyndon Johnson—having a particularly close relationship with Dwight Eisenhower as an extension of a professional bond forged during WW II. She served in Congress until 1968 when Charles Vanik defeated her.

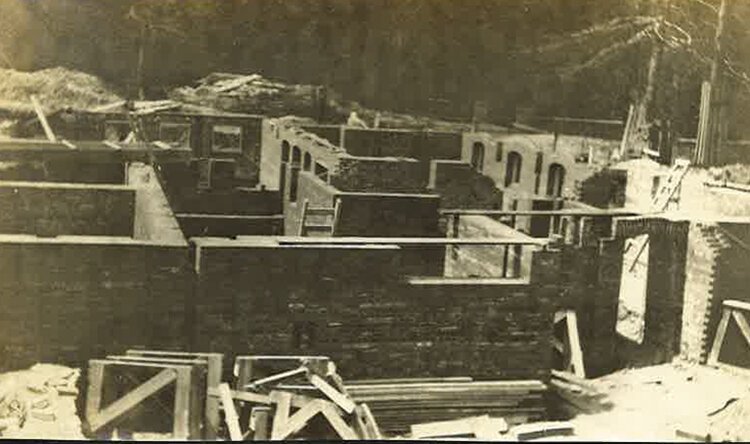

Frances Payne Bolton’s Lyndhurst home, Franchester, a colonial revival house on 110 acres with construction begining in 1914 and completed in 1917.Bolton returned to her Lyndhurst home, known as Franchester. Construction of this colonial revival house on 110 acres began in 1914 and was completed in 1917.

Frances Payne Bolton’s Lyndhurst home, Franchester, a colonial revival house on 110 acres with construction begining in 1914 and completed in 1917.Bolton returned to her Lyndhurst home, known as Franchester. Construction of this colonial revival house on 110 acres began in 1914 and was completed in 1917.

The architect chosen was Prentice Sanger. His association with the family began when he and Chester Bolton were Harvard roommates in the early 1900s. Sanger was born in Newport, Rhode Island in 1881. A graduate of Groton School, he was a member of the Harvard Class of 1905. He spent two more years at Harvard after graduation, studying landscape architecture before opening his own office in New York City in 1908.

Sanger characterized his practice as specializing in grand houses of the colonial revival style—and Franchester is a perfect example of his style.

Notable for its great size—about 27,350 square feet—the house has a very unusual feature: A living room decorated with paneling from an English manor house once occupied by 19th Century renowned British Royal Navy officer Lord Nelson and Lady Hamilton.

The house was the centerpiece of a large working farm, noted for its herd of prize Guernsey cattle. It also figured in generosity to the community when the Boltons donated a tract of adjoining land for the creation of Hawken School.

Near relations built grand houses nearby. In 1920, Bolton’s sister and brother-in-law, Elizabeth Bingham Blossom and Dudley S. Blossom, bought 22 acres next door and built their own home.

Frances Payne Bolton died at Franchester in March 1977 at the age of 91. Both Frances and Chester are buried at Lake View Cemetery.

Much of the Bolton and Blossom land today makes up the former TRW headquarters and Legacy Village.

Much of the Bolton and Blossom land today makes up the former TRW headquarters and Legacy Village.

TRW donated the 90-acre campus to the Cleveland Clinic Foundation in 2002, but the entire campus—including the Bolton estate—is once again up for sale.

The property is heavily wooded, and notable for its extensive stonework, lawns, and gardens. The house itself is a remarkable survivor, an evocative remnant of a lifestyle that has nearly vanished.

It is also a vivid reminder of a life that ought to be remembered.

Resisting any temptation she may have felt to live a life of self-indulgence, Frances Payne Bolton chose instead to work hard on behalf of others, living a life of great usefulness to her community and to her country.

Her beloved home stands deserted, surrounded by tranquil grounds, hoping for a future befitting its storied past.

Watch a documentary of Frances Payne's Bolton's life here.

About the Author: Tom Matowitz

Recently retired after a 37-year career teaching public speaking, Tom Matowitz has had a lifelong interest in local and regional history. Working as a freelance author for the past 20 years he has written a number of books and articles about Cleveland’s past. He has a particular interest in the area’s rich architectural history.