Margaret Bourke-White, first female photojournalist authorized to shoot in World War II combat

In the mid-20th Century Margaret Bourke-White became one of the world’s best-known photojournalists.

She was an American war correspondent during World War II and in 1942 became the first woman authorized to enter combat zones to photograph in battle. During the war, Bourke-White flew a combat mission in a B-17 “Flying Fortress” Bomber and found herself escaping a sinking ship by jumping over the side into a lifeboat.

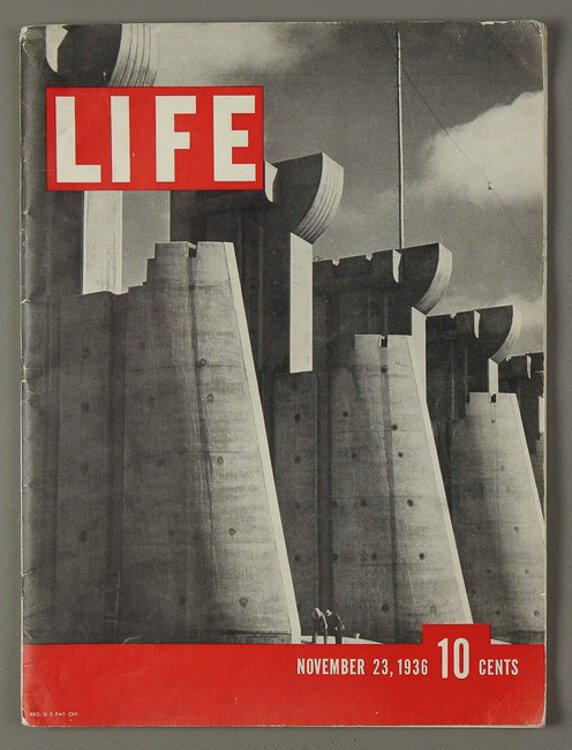

Margaret Bourke-WhiteEarlier in her career, in 1937, Bourke-White’s photograph of Fort Peck Dam under construction became the cover of the first issue of “Life Magazine.”

Margaret Bourke-WhiteEarlier in her career, in 1937, Bourke-White’s photograph of Fort Peck Dam under construction became the cover of the first issue of “Life Magazine.”

What is less known today is that Bourke-White’s career began in Cleveland, after first coming to the area to study at Western Reserve University in the early 1920s.

Born in 1904 and one of three children, her brother, Roger Bourke-White, was a prominent businessman who made an important place in Cleveland history for himself as the co-founder of fiberglass insulator manufacturer Glastic Corporation.

Both Roger and Margaret attributed their successes to drive and self-confidence—inherited from their parents, who both encouraged them to follow their dreams from childhood.

Margaret came by her interest in photography as a youngster—inspired by the work and influence of her father, Joseph White.

After attending several colleges, including Western Reserve, Margaret graduated from Cornell University in 1927. A year later she moved to Cleveland and opened a commercial photography studio with an emphasis on architectural and industrial subjects.

She quickly ingratiated herself to several very influential Cleveland business leaders, thereby gaining access to some very unusual subject matter.

Terminal Tower 1928Bourke-White’s subjects ranged from Cleveland’s steel mills to formal gardens in Gates Mills. Her timing was excellent, as downtown Cleveland was being transformed by the 1927 completion of the Terminal Tower complex.

Terminal Tower 1928Bourke-White’s subjects ranged from Cleveland’s steel mills to formal gardens in Gates Mills. Her timing was excellent, as downtown Cleveland was being transformed by the 1927 completion of the Terminal Tower complex.

She found innovative solutions to technical challenges, such as having assistants use magnesium flares to illuminate the steel mills while she shot action photos.

While developing her career, she reinvented herself—leaving a brief and unsatisfactory marriage and adding her mother’s maiden name to her birth name, adopting the surname Bourke-White.

As Bourke-White’s career continued to evolve, she developed an excellent reputation for her steel mill photos that helped win her a job at “Fortune Magazine” in 1929. She remained there until 1935. The following year, at the age of 32, she landed one of the best photography jobs in the country as the first woman hired as a photojournalist by “Life Magazine.”

Bourke-White’s niche continued to be photographing industrial subjects—declaring they were beautiful, precisely because they were not intended to be. But she was also known for capturing human emotion in her photograph of Black flood victims after the 1937 Louisville Flood who were lined up to get food and clothing from the Red Cross relief in front of a billboard the stated “World’s highest standard of living/ there’s no way like the American way.”

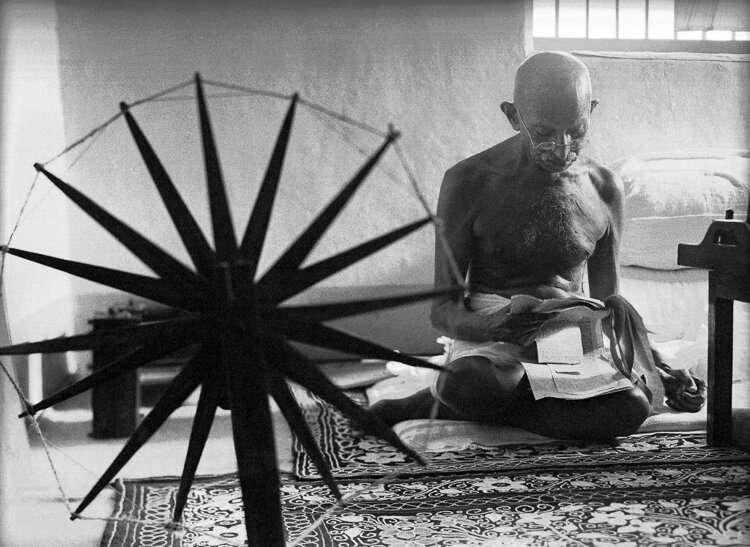

In 1946, Bourke-White photographed Mahatma Gandhi in India. Among other historical figures, she photographed Joseph Stalin and Winston Churchill.

Life photographer Margaret Bourke-White prepares to photograph an air battle on the Italian front during World War II, 1943During World War II she documented a degree of violence unseen by many men. In 1945 she accompanied U.S. soldiers who liberated Buchenwald concentration camp near Weimar, Germany—documenting the genocide practiced there.

Life photographer Margaret Bourke-White prepares to photograph an air battle on the Italian front during World War II, 1943During World War II she documented a degree of violence unseen by many men. In 1945 she accompanied U.S. soldiers who liberated Buchenwald concentration camp near Weimar, Germany—documenting the genocide practiced there.

Bourke-White said she was grateful for the camera that provided a barrier between herself and the horrors she witnessed.

It was a long way from formal gardens in Gates Mills.

While many men of her generation felt fighting in one war was enough, Bourke-White went on to document the Korean War—just five years after being at Buchenwald.

Her later years were difficult. As the Korean War ended, Bourke-White was nearing 50.

She began experiencing symptoms of Parkinson’s Disease. The disease progressed quickly, and soon impacted her ability to work. Her speech became impaired, and she became increasingly isolated.

Bourke-White died of Parkinson’s Disease in 1971 at the age of 67. Her ashes were scattered in an unknown location, but she is remembered in Cleveland by examples of her work on display at the Cleveland Museum of Art.

About the Author: Tom Matowitz

Recently retired after a 37-year career teaching public speaking, Tom Matowitz has had a lifelong interest in local and regional history. Working as a freelance author for the past 20 years he has written a number of books and articles about Cleveland’s past. He has a particular interest in the area’s rich architectural history.