Daniel H. Burnham and John Wellborn Root: Designers of the first skyscrapers

For a matter of 18 years Daniel H. Burnham and John Wellborn Root led one of the most influential firms in American architecture.

Their greatest impact was their pioneering use of structural steel framework to permit the construction of high-rise buildings. Earlier structures relied on masonry walls for support—making them limited in terms of height (buildings with masonry walls could be no taller than 12 stories). Their use of steel internal framing made this limit obsolete and led to the very tall buildings taken for granted today.

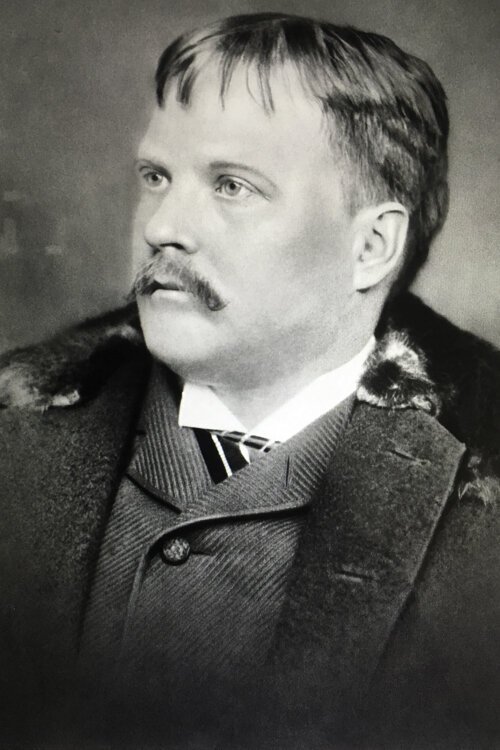

John Wellborn RootBurnham and Root were based in Chicago and made their reputation there.

John Wellborn RootBurnham and Root were based in Chicago and made their reputation there.

Less well known is the extent of their work in Cleveland—two of the three downtown buildings still grace the Cleveland skyline today.

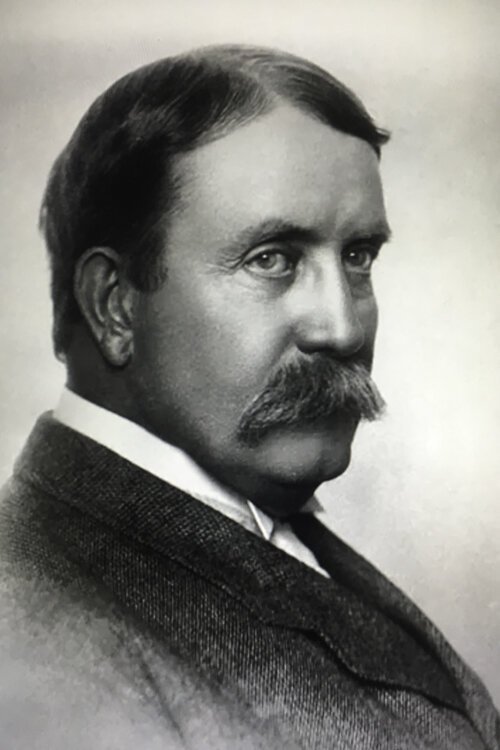

Burnham was a native of New York, having been born in the upstate community of Henderson in September 1846. He tried his hand at several careers before settling upon architecture. The Chicago Fire of October 1871 destroyed more than 2,000 acres of property in the city and subsequently created great demand for architects during the rebuilding period.

At the age of 26 Burnham went to work in the Chicago firm of Carter, Drake, and Wight. He formed a friendship with a new coworker, John Wellborn Root. In 1873 the two young men formed the partnership Burnham and Root and went into business together.

Root was four years younger than Burnham, having been born in 1850 in the town of Lumpkin Georgia.

Too young to have served in the Confederate Army, the war still had a profound impact on Root’s life. After Atlanta fell to Sherman’s army, Root’s father sent him through the blockade to Liverpool, England where his grandfather ran a business.

Daniel H. BurnhamRoot attended the Clare Mount School while living in Liverpool and took careful notice of the work of local architect Peter Ellis—who designed the first metal framed glass curtained walled buildings ever constructed.

Daniel H. BurnhamRoot attended the Clare Mount School while living in Liverpool and took careful notice of the work of local architect Peter Ellis—who designed the first metal framed glass curtained walled buildings ever constructed.

With the end of the Civil War, Root returned to the United States and earned an undergraduate degree at New York University in 1869.

Moving to Chicago in 1871 he took a job as a draftsman in an architectural firm. His partnership with Daniel Burnham began two years later.

In 1879 Root married Mary Louise Walker. This proved to be a tragic episode in his life as she died of tuberculosis only six weeks after their wedding. Three years later he married Dora Louise Monroe. His son from this marriage, John Wellborn Root Jr., grew up to be one of Chicago’s best known 20th Century architects.

Burnham married Margaret Sherman in 1876 and they had three sons. Two sons, Hubert and Daniel Jr., became architects, beginning their careers in their father’s firm. Margaret survived her husband by 32 years, dying in 1945 at the age of 95.

The pair’s skyscraper design career took off in the late 1800s in Chicago.

Burnham and Root’s first steel framed skyscraper, the 1889 Rand McNally Building on Adams Street in Chicago, was 10 stories tall, stood at 148 feet tall, and cost $1 million to build (it was demolished in 1911 to make way for a larger building).

Burnham and Root designed three important buildings in Cleveland. Practically within sight of each other, the survivors have been downtown landmarks for 130 years.

Society For Savings on Public SquareBut a year later, in 1890, came the Society For Savings on Public Square—at 152 feet tall with 10 stories, it was considered the first modern skyscraper in Ohio and was the tallest building in Cleveland (until 1896, when it was surpassed by the 221-foot Guardian Bank Building).

Society For Savings on Public SquareBut a year later, in 1890, came the Society For Savings on Public Square—at 152 feet tall with 10 stories, it was considered the first modern skyscraper in Ohio and was the tallest building in Cleveland (until 1896, when it was surpassed by the 221-foot Guardian Bank Building).

Designed in the Richardsonian style Root so admired, the building has been carefully refurbished and remains a local gem.

The 1892 Western Reserve Building is located on Superior Avenue at the edge of the Flats. For years the eight-story building was the location of the office of Cleveland business mogul and philanthropist Samuel L. Mather. The building was renovated by the Higbee Development Company in 1976, when the Romanesque entrance arch, which had been altered with granite facing in the 1940s, was restored. The building stands today.

The third building was the 1893 Cuyahoga Building, also located on Public Square. This eight-story structure was notable as the first office building constructed in Cleveland with a structural steel framework.

Being newly refurbished and listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1975 did not save the building from destruction. In 1982 it was imploded along with its George B. Post-designed neighbor, the Williamson Building, to clear the site for construction of the Sohio Building (aka, the BP Tower).

In a great irony the new building became the headquarters of BP America which shortly elected to move operations to Chicago. Within just a few years of its construction the Sohio brand had vanished from Ohio roadways and the firm’s onetime headquarters lost its identity. All glory is fleeting.

The firm of Burnham and Root didn’t last much longer after these three buildings were designed. After a three-day illness, Root died of pneumonia at the early age of 41, thus dissolving the partnership in 1891.

The Cuyahoga Building 1906Burnham continued in business as D.H. Burnham & Company and remained active in Chicago until his death in the spring of 1912.

The Cuyahoga Building 1906Burnham continued in business as D.H. Burnham & Company and remained active in Chicago until his death in the spring of 1912.

Earlier that spring, Burnham traveled to Europe on vacation. His friend Frank Millet (who painted the murals that decorate the 1907 Cleveland Trust Rotunda to this day) was heading in the opposite direction—returning to the United States after an extended visit to Europe.

Burnham sent Millet a telegram as a friendly greeting and was stunned to receive a reply noting that Millet was lost in the sinking of Titanic. The shock was said to have contributed to Burnham’s death just weeks later.

The successor firm of Burnham’s practice, Graham, Anderson, Probst, and White, went on to great success and remained in operation until 2006—carrying the legacy of Burnham and Root into the 21st Century.

About the Author: Tom Matowitz

Recently retired after a 37-year career teaching public speaking, Tom Matowitz has had a lifelong interest in local and regional history. Working as a freelance author for the past 20 years he has written a number of books and articles about Cleveland’s past. He has a particular interest in the area’s rich architectural history.