Cudell & Richardson: Known for five historic buildings and churches, one haunted house

While the firm of Cudell & Richardson existed for fewer than 20 years, its impact on Cleveland architecture is still felt 130 years after the firm’s last design was completed.

Partners Frank Cudell and John Richardson designed an array of well-known commercial buildings, churches, and one private residence believed in popular culture to be the most haunted house in Ohio.

It is noteworthy that five Cleveland buildings designed by these men survived to be listed on the National Register of Historic Places.

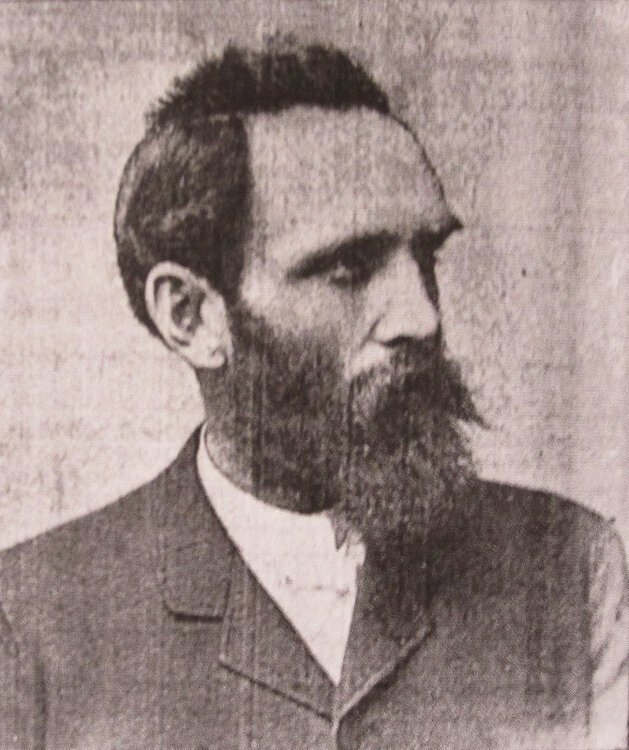

Both partners in this firm were born abroad and immigrated to Cleveland as young men. Frank Cudell was born near Aachen, Germany while John Richardson was a native of Scotland.

The exterior of the Perry Payne Building on Superior avenue as it appeared in the 1880sThey began working together in 1871 and their best-known commercial structure is the Perry-Payne Building on Superior Avenue. The building took its name from owner Henry B. Payne and his wife, whose maiden name was Mary Perry. Both families were influential in Cleveland life.

The exterior of the Perry Payne Building on Superior avenue as it appeared in the 1880sThey began working together in 1871 and their best-known commercial structure is the Perry-Payne Building on Superior Avenue. The building took its name from owner Henry B. Payne and his wife, whose maiden name was Mary Perry. Both families were influential in Cleveland life.

Payne served in both state and national governments, finishing his political career as a U.S. senator from Ohio. Payne’s son Oliver Hazard Payne made a vast fortune through his early involvement with Standard Oil. When the younger Payne died in 1917, he was said to be one of the wealthiest men in the country.

The Perry-Payne building attracted considerable attention when it was completed in 1888. At eight stories high, it was Cleveland’s tallest building when it was completed—losing its title just two years later to Burnham and Root’s 10-story Society For Savings Building on Public Square.

Perry-Payne had a steel internal structure and was notable for its large windows as well as its interior light court. Its design was considered so innovative that architects from around the country visited Cleveland to see it in person.

One of its early tenants was the Lake Carriers Association—a trade organization focused on reducing navigation hazards on the Great Lakes and making improvement recommendations. For many years it provided a desirable business address for a number of firms involved in Great Lakes shipping or the iron ore trade.

Placed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1973, the Perry-Payne building was remodeled into apartments in the mid-1990s.

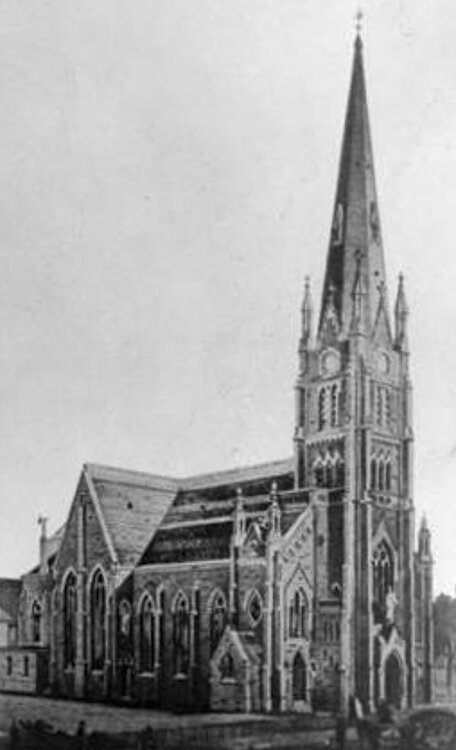

St. Stephen Roman Catholic Church, ExteriorCudell & Richardson’s Gothic inspired St. Stephen Roman Catholic Church was built in 1875 to serve a recently created German parish on Cleveland’s near west side. It eventually became the largest German-speaking catholic parish in Cleveland.

St. Stephen Roman Catholic Church, ExteriorCudell & Richardson’s Gothic inspired St. Stephen Roman Catholic Church was built in 1875 to serve a recently created German parish on Cleveland’s near west side. It eventually became the largest German-speaking catholic parish in Cleveland.

Its substantial construction of granite blocks proved a lifesaver when the church met with an unusual mishap on June 8, 1953. That day it was damaged by a tornado—damaging or destroying the stained-glass windows. A lesser building may well not have survived. Repairs took more than a year and the church did not reopen until November 1954.

Listed on the National Register in 1977, the church remains in active use today.

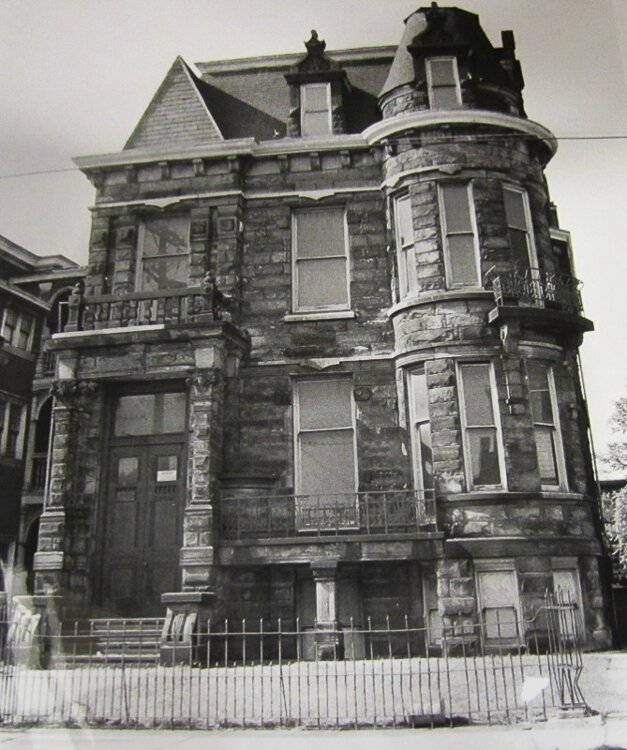

The firm’s most controversial building is the Hannes Tiedemann House on Franklin Avenue on Cleveland’s west side. Popularly known as Franklin Castle, this house has had a lurid history.

Hannes Tiedemann was one of the multitudes who fled Germany after the failed revolution of 1848. He immigrated to Cleveland and made a fortune in the banking industry. His family life was unhappy, with a child dying young and the unexpected death of his wife. He remarried, only to see that marriage end in divorce a year later.

Later owners of the house included a Cleveland police chief and a dot-com millionaire. Along the way the house acquired the reputation of being haunted—something it has never lived down.

Despite its reputation, Franklin Castle was placed on the National Register in March 1982.

Despite its reputation, Franklin Castle was placed on the National Register in March 1982.

One of the firm’s lost buildings was St. Joseph’s Church and Friary, once located on East 23rd Street and Woodland Avenue. Constructed in the 1870s and placed on the National Register a century later in 1976, the church was an imposing Gothic structure made of brick and notable for the fact that it served a German immigrant congregation in its native language.

St. Joseph’s dwindling parish was eviscerated by interstate highway construction in the 1960s. The church was basically surrounded and cut off by I-90 and I-77. The church stood alone on the east side of I-77 as the highway approached Cleveland.

A grid of streets remained but the church stood alone, without a single other building nearby. It was a desolate scene.

St. Joseph was deconsecrated in 1986 and many of its decorations were removed and placed in other churches. After a disastrous fire in 1993, what remained of the building was demolished.

The firm’s final National Register Building is the Bradley Building. Located on West 6th Street in the Warehouse District, the structure was originally known in 1887 as the Root-McBride Building. Converted to apartments, the building remains in daily use.

Upon his death in 1916 Cudell left property to the City of Cleveland. The land became the nucleus of the Cudell Recreation Center. He is buried in Lake View Cemetery.

John Richardson continued as an independent architect after his partnership with Cudell ended. One of his final projects was the Jennings Apartments located on West 14th Street—said to be the first apartment building in Cleveland equipped with an elevator.

Richardson died in 1902 and was buried in Riverside Cemetery.

About the Author: Tom Matowitz

Recently retired after a 37-year career teaching public speaking, Tom Matowitz has had a lifelong interest in local and regional history. Working as a freelance author for the past 20 years he has written a number of books and articles about Cleveland’s past. He has a particular interest in the area’s rich architectural history.