Dunham Tavern: A piece of the 1820s in MidTown

Very few buildings in the Cleveland area can claim a lifespan approaching two centuries. One of these remarkable survivors is Dunham Tavern Museum & Gardens, which will celebrate its 200th birthday next year.

This venerable structure has seen everything—Cleveland’s growth from a transplanted New England Village to an industrial giant, to the rise and fall of Millionaire’s Row.

Dunham Tavern was occupied by J.A. Stephens in 1917Part of the early migration from the East, Massachusetts natives Rufus and Jane Pratt Dunham arrived in Cleveland in 1819. The plot of land they purchased amounted to almost 114 acres and cost the grand sum of $147.

Dunham Tavern was occupied by J.A. Stephens in 1917Part of the early migration from the East, Massachusetts natives Rufus and Jane Pratt Dunham arrived in Cleveland in 1819. The plot of land they purchased amounted to almost 114 acres and cost the grand sum of $147.

Their first Cleveland residence was a log cabin, which was replaced five years later by the original 1824 frame house on the site. The tavern is the oldest building in Cleveland still standing on its original site.

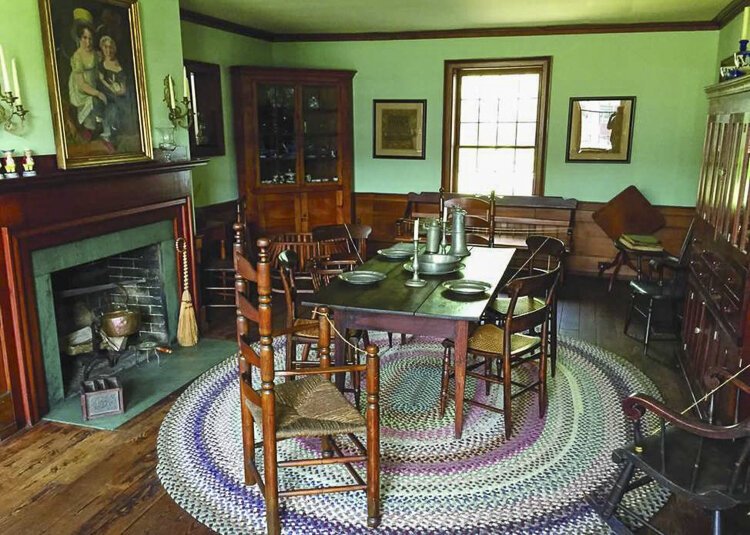

The house was a considerable improvement over the log cabin. It was two stories, with two rooms on each floor separated by a central hallway, with a one-story wing projecting to the rear.

By the 1840s the building included sleeping quarters and a taproom to accommodate stagecoach drivers on the Buffalo-Cleveland-Detroit Road, as Euclid Avenue was then known.

Cleveland’s population in the 1840s was 6,071—a tenfold increase since the 1820s.

In this era Dunham Tavern was a busy place. It hosted political meetings for the long-forgotten Whig party, as well as a gathering place to turkey shoots and other social functions that drew large numbers of people to visit, making it very familiar to a generation of Clevelanders and their guests.

Women in costume pose at the fireplace in the Dunham Tavern Museum 1960The tavern’s time as a gathering place for travelers ended abruptly in 1857, presumably because the Dunhams were ready to retire.

Women in costume pose at the fireplace in the Dunham Tavern Museum 1960The tavern’s time as a gathering place for travelers ended abruptly in 1857, presumably because the Dunhams were ready to retire.

The building was sold and converted to a single-family dwelling, a function it served for the remainder of the 19th Century.

Leading a quiet life in the early years of the 20th Century, The Dunham Tavern’s biggest accomplishment was surviving. The immediate vicinity experienced commercial development, changing the views from the house in ways the Dunhams could never have imagined.

Buffalo-Cleveland-Detroit Road had long since morphed into paved Euclid Avenue and streetcars and automobiles took the place of stagecoaches.

Three-quarters of century after the Dunhams lived there, Dunham Tavern entered a new era when A. Donald Gray purchased the building in 1932.

One of the finest landscape architects ever to work in Cleveland, Gray carefully restored the building over the next several years. In addition to restoring many lost 19th Century details to the house, he replanted a long-gone orchard.

Gray also made the house available for use as a studio by Works Progress Administration (WPA) artists and print makers.

The WPA was a function of Franklin Roosevelt’s New Deal, a 1930s program intended to provide gainful employment for artists and writers in their fields of expertise instead of allowing the Depression to squander their talents.

This golden age under Gray’s ownership was unfortunately destined to be short lived.

After several years of unusually productive work, Gray died suddenly of a heart attack on May 30, 1939, at the early age of 48.

But he had made good arrangements for the future of Dunham Tavern. In 1936 Roberta Holden Bole, a major benefactor to many museums in Cleveland and helped establish Holden Arboretum, worked with furniture designer and architectural historian Ihna Thayer Frary to found the Dunham Tavern Corp. to collect funds to save the historic Tavern from destruction.

But he had made good arrangements for the future of Dunham Tavern. In 1936 Roberta Holden Bole, a major benefactor to many museums in Cleveland and helped establish Holden Arboretum, worked with furniture designer and architectural historian Ihna Thayer Frary to found the Dunham Tavern Corp. to collect funds to save the historic Tavern from destruction.

Dunham Tavern opened to the public as a museum two years After Gray’s death. The tavern is listed on the National Register of Historic places and was designated a Cleveland landmark in 1973.

Located at 6907 Euclid Avenue, the museum is subject to loving care and has been a perennial destination for area school field trips. In 2021 officials began implementing a master plan to preserve the museum’s history and plan for its future.

It may be seen today in a form that Rufus and Jane Dunham would easily recognize, even though the environment around it has been transformed by two centuries of change, not all of it conducive to peace and quiet.

It is one of the few places people can visit today to get a vivid impression of Cleveland life in the 1820s.

About the Author: Tom Matowitz

Recently retired after a 37-year career teaching public speaking, Tom Matowitz has had a lifelong interest in local and regional history. Working as a freelance author for the past 20 years he has written a number of books and articles about Cleveland’s past. He has a particular interest in the area’s rich architectural history.