Graham, Anderson, Probst, and White: The firm that designed three notable CLE landmarks

The renowned Chicago architectural firm Burnham & Root designed remarkable office buildings that defined Cleveland’s skyline in the last years of the 19th Century.

But a generation later, after Daniel Burnham’s 1912 death, Burnham and Root evolved intoGraham, Anderson, Probst, and White. The noted firm designed structures that symbolized Cleveland’s 1920s prosperity. While few in number, these buildings are landmarks that have never been surpassed.

Graham was the principal architect of three notable buildings in Cleveland: the 1918 Hotel Cleveland, the 1924 Union Trust Building, and the 1930 Terminal Tower.

These three building were recognized for the scope and quality of their designs when they were new, and nearly a century after construction they continue to serve their original purposes.

They have undergone sensitive restoration and remain key elements of the Cleveland skyline.

Union Trust 1920sUnion Trust Building

Union Trust 1920sUnion Trust Building

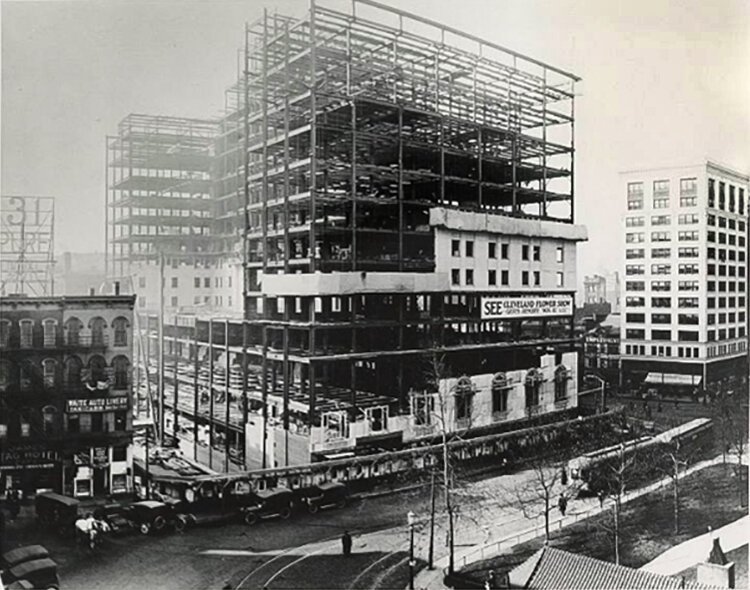

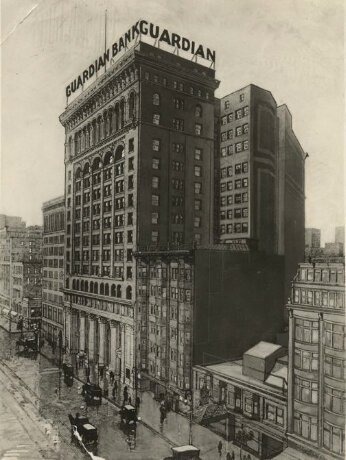

Construction of the Union Trust Bank Building at East 9th Street and Euclid Avenue. required three years, with Union Trust opening for business in 1924.

The building was huge—the floor plan amounted to 1 million square feet, or 30 acres, and the banking room was said to be the largest in the world and one of the largest office buildings in the world. This space certainly leaves a dramatic first impression with columns soaring into the vaulted ceiling.

The Union Trust building reflected the image of substance and permanence that banks in the 1920s took pains to promote. It was not without irony in this case. On February 25, 1933—one of the worst days in Cleveland banking history—a large number of restless depositors descended upon the Union Trust and Guardian Trust Banks. Their collective withdrawals cost these banks half their deposits before dinner time. The result was disastrous, eventually driving both of these major banks out of existence leaving great hardship in their wake.

It sent Union Trust into receivership and ultimately out of existence. The building survived as the headquarters of several subsequent Cleveland banks and provided an office for William G. Mather, likely the most successful Cleveland businessman of his generation. As president and board chairman of Cleveland-Cliffs in the Union Trust building, Mather commuted to work from his home in Bratenahl in a chauffeur-driven Rolls Royce.

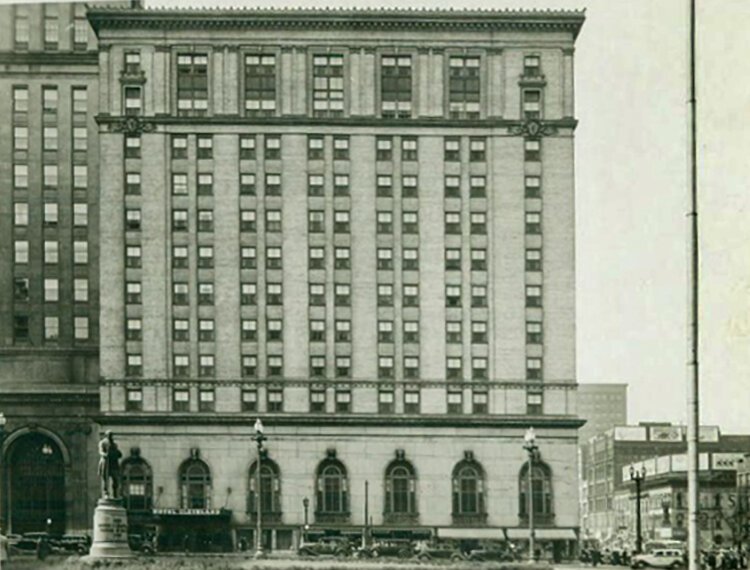

Hotel Cleveland 1940sHotel Cleveland

Hotel Cleveland 1940sHotel Cleveland

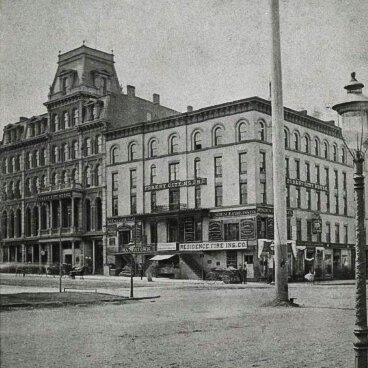

Several years earlier, the Graham, Anderson, Probst, and White firm designed the Hotel Cleveland on Public Square. Opened at the end of 1918, this grand new hotel took the place of the mid-19th Century Forest City House—a fixture on Public Square’s west side for the previous 60 years.

The new hotel quickly hosted many well-known personalities and events: Charles Lindbergh spoke there shortly after his epic solo flight across Atlantic and Eliot Ness was said to be a frequent visitor during his tenure as Cleveland’s safety director.

Terminal Tower and Public Square official openingTerminal Tower

Terminal Tower and Public Square official openingTerminal Tower

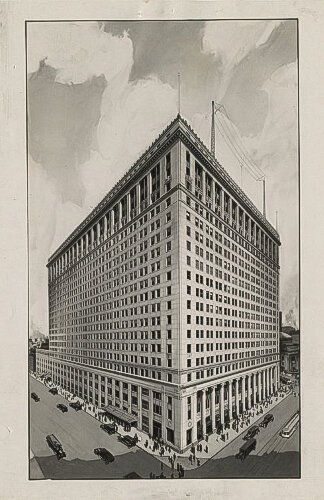

The Hotel Cleveland design attracted the attention of the Van Sweringen brothers who chose Graham, Anderson, Probst, and White to handle the design of their proposed Terminal Tower complex.

The choice seemed apt. At the time, the firm was the largest architectural firm in the United States and renowned for its ability to meet the responsibilities of large and complicated commissions.

The Terminal Tower project certainly met that criterion since its massive scale required demolition of more than 2,000 buildings and a quantity of earth moving said to have been surpassed only by the construction of the Panama Canal.

The Terminal Tower project took the best part of a decade to execute. The original concept called for a station on the lakefront roughly where the football stadium is now. With the decision to build on Public Square, land acquisition began in the early 1920s with the new building being dedicated in 1930.

The construction destroyed a large concentration of commercial buildings as well as Champlain, Michigan, and Long Streets. It was a vast permanent change in the Cleveland landscape and its completion coincided with the 1929 stock market crash. The Van Sweringens died broke by the mid-1930s.

After Graham, Anderson, Probst, and White’s work in Cleveland was completed with the dedication of the Terminal Tower in 1930, the firm continued for decades in Chicago until closing in 2006—almost 150 years after Daniel Burnham and John Welborn Root formed their original partnership in the aftermath of the Chicago Fire.

About the Author: Tom Matowitz

Recently retired after a 37-year career teaching public speaking, Tom Matowitz has had a lifelong interest in local and regional history. Working as a freelance author for the past 20 years he has written a number of books and articles about Cleveland’s past. He has a particular interest in the area’s rich architectural history.