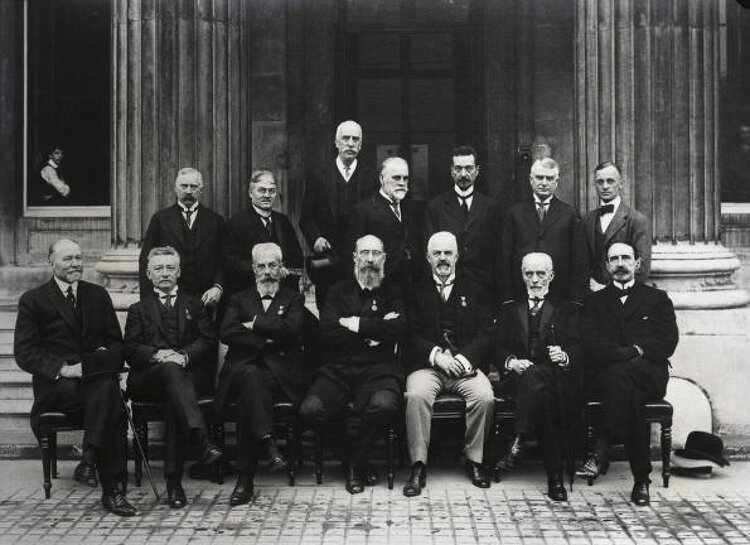

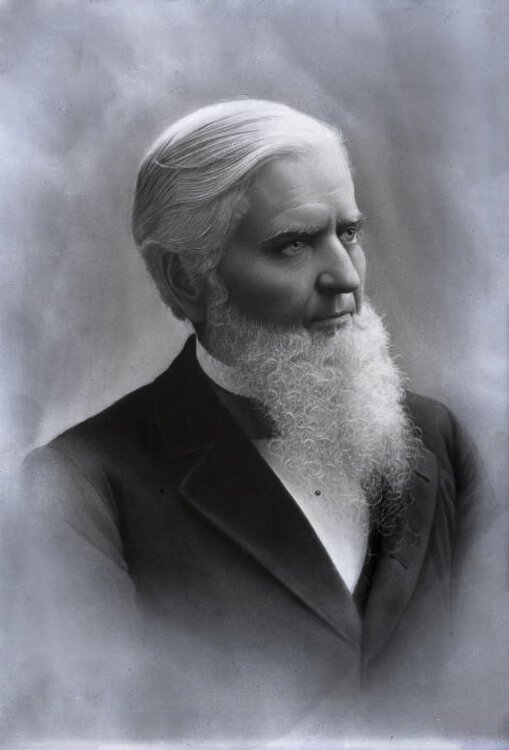

George Edmondson, well-known turn-of-the-century photographer

Photography became practical in the mid-19th Century—within the reach of the middle class and no longer a gimmick confined to a scientist’s laboratory.

Cities the size of Cleveland could boast studios where middle class residents could go and endure sitting still for the long exposure times required by the technical limitations of the early equipment of the day.

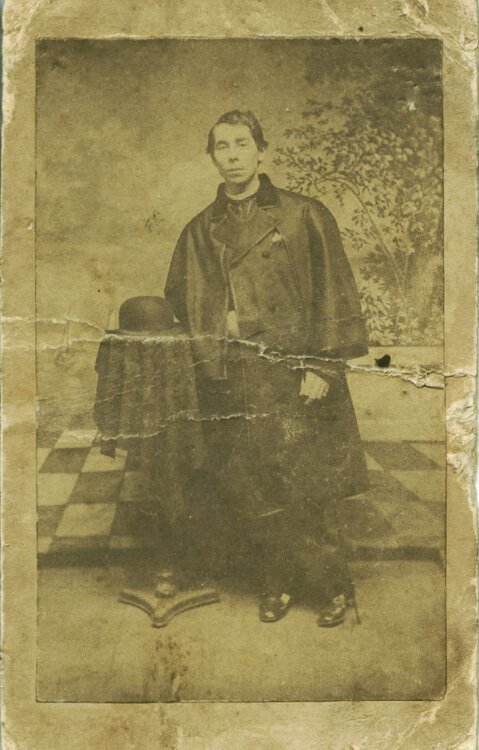

In 1862 a Confederate soldier on the battlefield of Antietam found this carte de visite (CdV) photograph taken in Cleveland of a man in a law enforcement uniform.

In 1862 a Confederate soldier on the battlefield of Antietam found this carte de visite (CdV) photograph taken in Cleveland of a man in a law enforcement uniform.

It is surprising how far some early Cleveland photographs traveled.

In the last days of September 1862, a Confederate soldier exploring the deserted battlefield of Antietam found a carte de visite (CdV) photograph of man in a law enforcement uniform. The back mark shows it to have been taken in Cleveland a year or so earlier. The image is of a Cleveland city marshal.

Held in the collections of the Cleveland Police Museum, it is the earliest known photograph of a Cleveland law man.

Most early photography was far more routine—images of people, buildings, and landscapes.

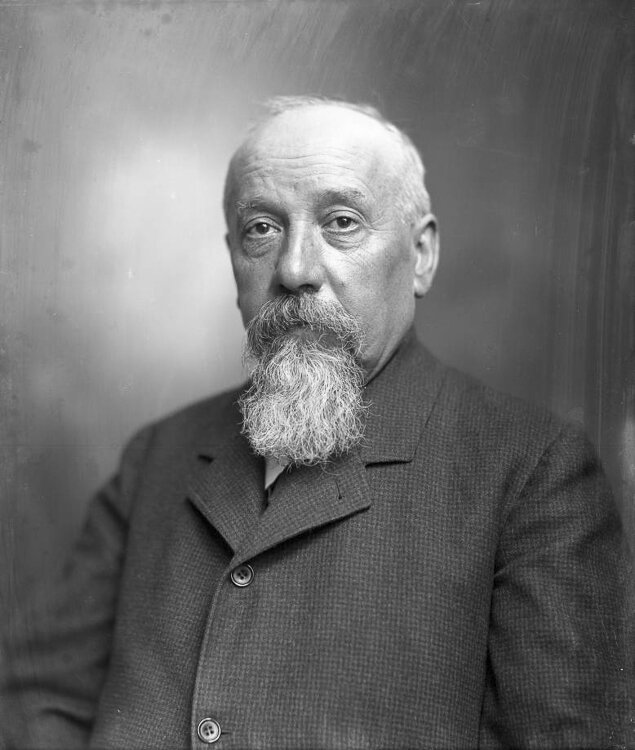

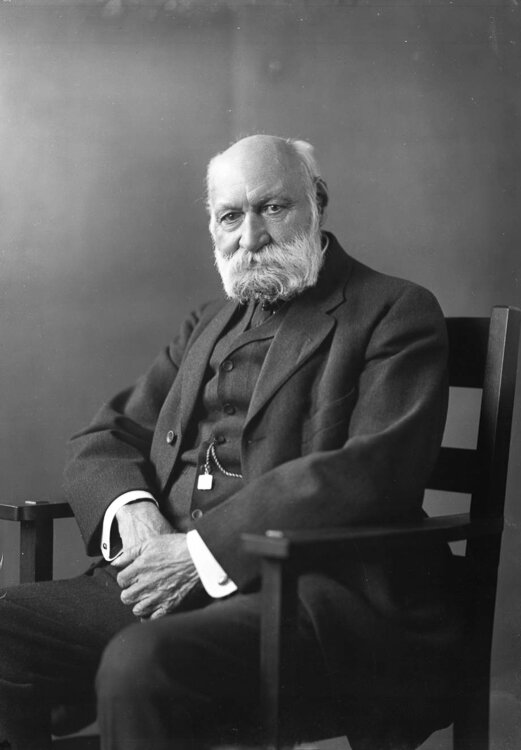

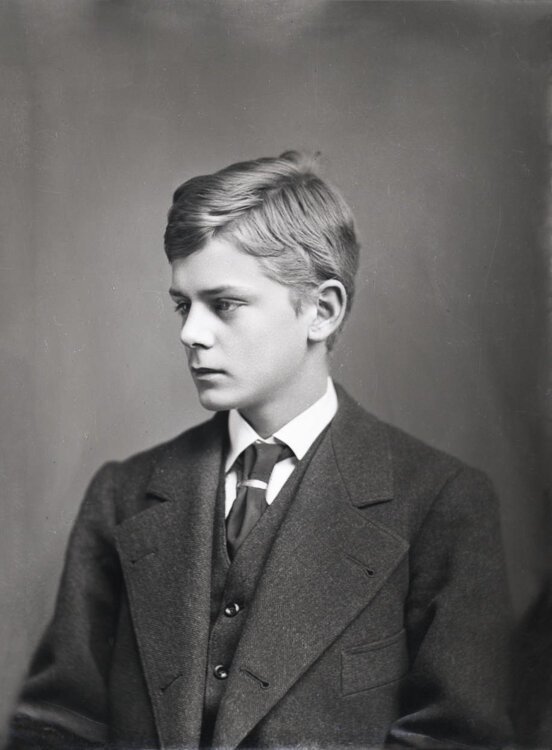

Certain photographers were destined for greatness. One of them was George Edmondson (1866 – 1948).

The son of an English immigrant who was himself a photographer, Edmondson was exposed to the art of photography early on. Born in Norwalk, he began a long apprenticeship under his father’s guidance. Mastering new technology as it emerged, by 1903 he had established his own independent studio in Cleveland at 510 Euclid Avenue.

George Mountain EdmondsonIn the early 1900s he became president of both the Photographers Association of Ohio and the Photography Association of America, as well as secretary and treasurer of the Professional Photographers Society of Ohio.

George Mountain EdmondsonIn the early 1900s he became president of both the Photographers Association of Ohio and the Photography Association of America, as well as secretary and treasurer of the Professional Photographers Society of Ohio.

Edmondson made portraits of Cleveland’s emerging middle and upper classes. He also became renowned for the quality of his architectural photography, which remains highly regarded to this day.

He had an eye for composition, and his finished prints were the models of sharpness and clarity.

Edmondson was in-demand by area architects who wanted to provide portfolios to their clients that highlighted the appearance of newly completed showplaces.

On occasion, Edmondson returned to these sites years later to record the interiors of these grand houses for insurance purposes. This practice showed gradual changes over time, illustrated how landscaping and formal gardens changed and grew.

His photographs of human subjects showed them in the best possible light, while the images of the houses they lived in brought these structures to life and made them into homes rather than simply rooms adorned with furniture.

Photo taken by George Edmondson to document Franchester circa 1919It is important to remember that all this took place in an era when photographers had to wait hours, if not days, to see the results of their work as it emerged in the darkroom.

Photo taken by George Edmondson to document Franchester circa 1919It is important to remember that all this took place in an era when photographers had to wait hours, if not days, to see the results of their work as it emerged in the darkroom.

It taxed their imaginations and their abilities to accurately visualize the results of their efforts.

Cleveland was destined to produce other great photographers, notably Margaret Bourke-White, but no one else has matched the quality or the range of the output from George Edmondson, or his longevity.

We are fortunate to be able to use his work as a window to look back into a glorious era of Cleveland’s past.

About the Author: Tom Matowitz

Recently retired after a 37-year career teaching public speaking, Tom Matowitz has had a lifelong interest in local and regional history. Working as a freelance author for the past 20 years he has written a number of books and articles about Cleveland’s past. He has a particular interest in the area’s rich architectural history.