Rockefeller Park: The crown jewel of University Circle; the vision of 19th Century benefactors

After 100 years, Rockefeller Park in University Circle remains one of Cleveland’s most beloved outdoor spaces. It is the direct result of the collaboration of several benefactors and visionaries whose generosity has benefited generations of Clevelanders.

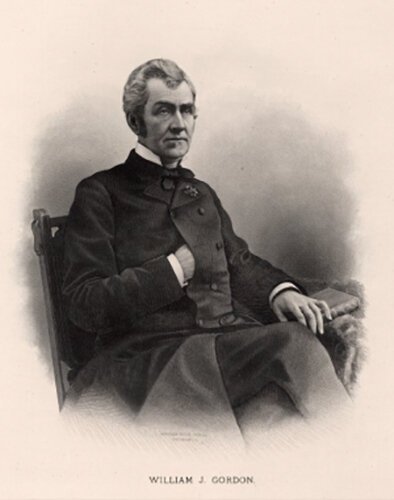

The idea for what is today’s 200-acre Rockefeller Park began in 1890—a product of the imagination of noted Cleveland businessman William J. Gordon.

The initial idea grew to include a landscaped boulevard that once honored the memory of Cleveland soldiers and sailors who lost their lives in World War I, and now recognizes the life and work of the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.

Along the way it grew to include the Cleveland Cultural Gardens—33 gardens honoring the diverse ethnic groups who have formed the city’s immigrant population.

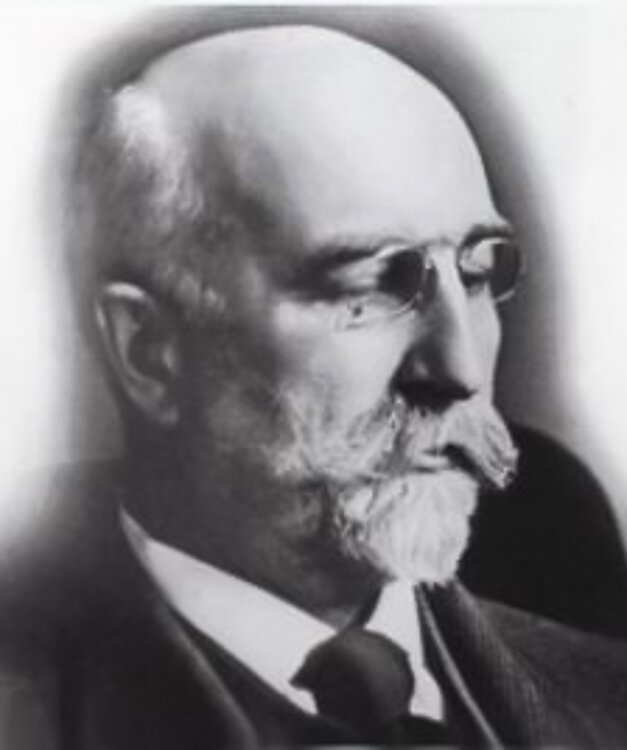

William J. Gordon made his mark on Cleveland in the mid-1800s as respected grocer who shipped iron ore on Lake Erie, and then left a piece of lakefront land to the city for perpetual enjoyment.

Born in Monmouth, New Jersey in 1818, William J. Gordon arrived in Cleveland in 1839. Having learned the wholesale grocery business in New York City, he established W.J. Gordon & Co., which quickly became the largest grocery supplier in Ohio.

William J. GordonIn 1853 he partnered with Samuel Kimball to ship the first load of iron ore from Minnesota to Cleveland, ushering in a century of heavy industry in the Flats—transforming Cleveland into a center of steel making and manufacturing.

William J. GordonIn 1853 he partnered with Samuel Kimball to ship the first load of iron ore from Minnesota to Cleveland, ushering in a century of heavy industry in the Flats—transforming Cleveland into a center of steel making and manufacturing.

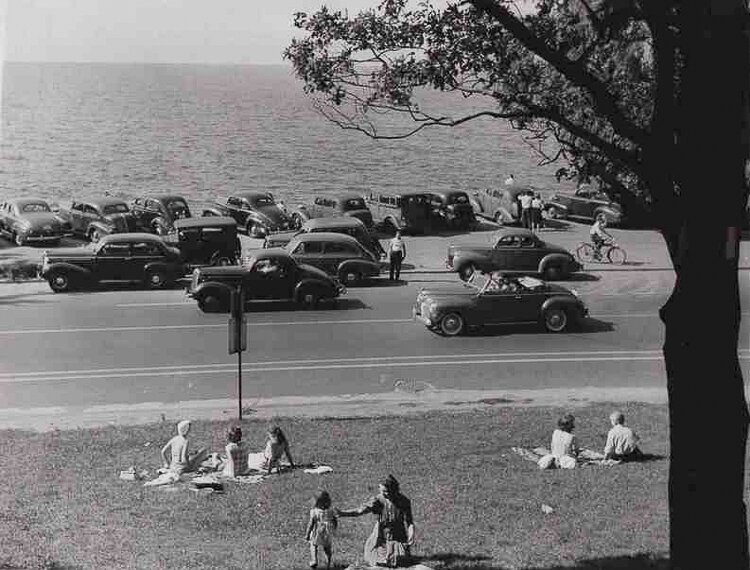

As he prospered, Gordon began acquiring land on the city’s east side, transforming a lakefront tract of 122 acres by University Circle into a park-like landscape.

In 1890 he approached noted landscape architect Ernest W. Bowditch to prepare a plan for a boulevard to join his property with Wade Park, generally following the course of Doan Brook, and passing through property owned at the time by John D. Rockefeller—what is today’s Martin Luther King, Jr. Boulevard.

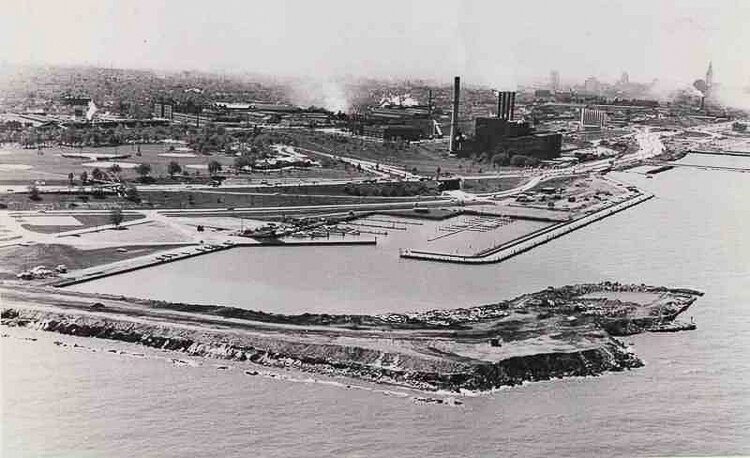

When Gordon died in 1892 his property was deeded to the city—his gift carrying the condition that the land would be a public park, maintained by Cleveland in perpetuity. The original Gordon Park, bordering Lake Erie on the eastern side of East 72nd Street, ceased to exist with the construction of the Lakeland Freeway in the 1960s.

Bowditch prepared an elaborate plan for this boulevard, and this was put in writing by December 31, 1894. It would easily be recognized by modern onlookers. As a note of interest, the location of the Cleveland Museum of Art is depicted in Wade Park 22 years before the museum was even built.

Well aware of the plans being made by Gordon and Bowditch, John D. Rockefeller in 1897 also deeded his connecting property to Cleveland so that Bowditch could expand his design and construction of the Rockefeller Park and the new boulevard could begin in earnest.

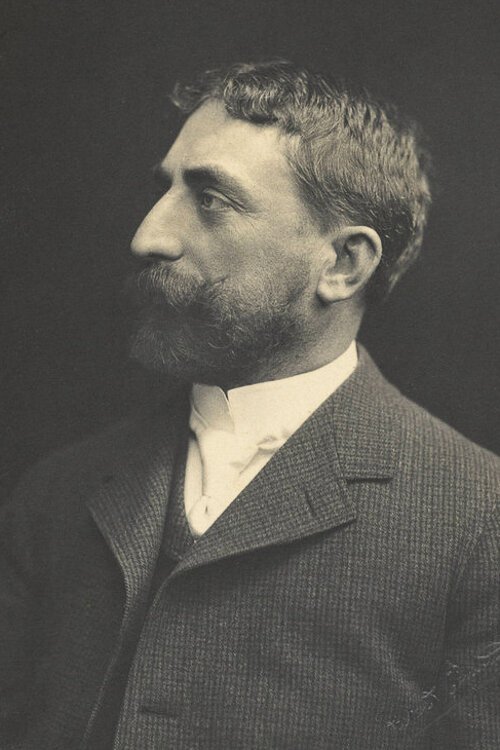

Ernest W. BowditchBowditch, a native of Brookline, Massachusetts, built his reputation on his exquisite park landscapes. He was educated at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology where he studied mining and chemistry before leaving after four years without completing a degree.

Ernest W. BowditchBowditch, a native of Brookline, Massachusetts, built his reputation on his exquisite park landscapes. He was educated at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology where he studied mining and chemistry before leaving after four years without completing a degree.

After a stint in Panama to help survey the eventual route of the Panama Canal, Bowditch returned to Boston and went to work for a civil engineering firm. His first task was a series of improvements to the Cambridge’s famous Mount Auburn Cemetery. He laid out new roads and paths and revised the cemetery’s landscaping.

Bowditch’s skills developed quickly and he went on to great success—designing the landscaping for The Breakers and Chateau-sur-Mer in Newport, Rhode Island, among other projects that drew national recognition.

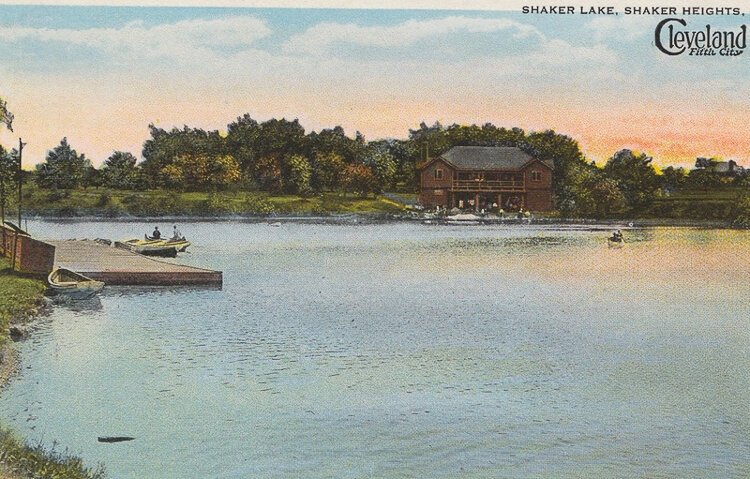

Bowditch’s other Cleveland works include Shaker Lakes Park as well as improvements and upgrades to Lake View Cemetery that he was commissioned to do in 1897.

Charles F. SchweinfurthProminent features on Rockefeller Park’s MLK Boulevard are the many bridges designed by Charles F. Schweinfurth, Cleveland’s preeminent architect of that time.

Charles F. SchweinfurthProminent features on Rockefeller Park’s MLK Boulevard are the many bridges designed by Charles F. Schweinfurth, Cleveland’s preeminent architect of that time.

The designs vary from bridge to bridge. They carry Wade Park Avenue, St. Clair Avenue, Superior Avenue, and the tracks of what was then the Lake Shore & Michigan Southern Railroad across the boulevard.

Completed between 1897 and 1900, the bridges survive to this day—their sturdy design easily handling a much heavier volume of traffic than they ever encountered when they were new.

Change came to the boulevard after World War I. Known as the Great War, and the War to End All Wars, this conflict cost the lives of 1,023 young men from Cleveland. Their sacrifice was remembered by the planting of a procession of oak trees running several miles long, with each tree identified with a specific soldier, sailor, or marine by a plaque. The area was dedicated, and the street renamed Liberty Boulevard on Memorial Day 1919.

The Shakespeare bust and the Shakespeare Garden (today known as the British Garden) were Dedicated in 1916 .Construction of a remarkable addition to the boulevard began with the dedication of the Shakespeare Garden in 1916 (today known as the British Garden). This proved to be the first in a series of the Cleveland Cultural Gardens that would recognize the multitude of ethnicities and culture that make up Cleveland’s population.

The Shakespeare bust and the Shakespeare Garden (today known as the British Garden) were Dedicated in 1916 .Construction of a remarkable addition to the boulevard began with the dedication of the Shakespeare Garden in 1916 (today known as the British Garden). This proved to be the first in a series of the Cleveland Cultural Gardens that would recognize the multitude of ethnicities and culture that make up Cleveland’s population.

Construction took place in three major stages and eventually saw completion of 33 distinct gardens highlighting the cultures they represent. They present a landscape unique in the United States.

The Cultural Gardens and Liberty Boulevard saw an interval of neglect in the 1960s and 70s. Maintenance of the gardens themselves was deferred. In the 1960s highway construction neatly bisected Gordon Park—essentially ruining the lovely spot created so carefully by William Gordon in the late 19th Century.

The public park that Gordon envisioned lasting forever through his will to the city in the end lasted just 60 years in the form the city received it.

In 1981 the boulevard along Doan Brook was renamed to honor the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. Forty years later stubborn Clevelanders of a certain age persist in referring to it by the name they grew up with.

By any name, the area has undergone a resurgence, with the various gardens restored and lovingly cared for. It is once again the showplace envisioned by its benefactors William Gordon, John D. Rockefeller, and Jeptha Wade, and its designer, Ernest W. Bowditch.

About the Author: Tom Matowitz

Recently retired after a 37-year career teaching public speaking, Tom Matowitz has had a lifelong interest in local and regional history. Working as a freelance author for the past 20 years he has written a number of books and articles about Cleveland’s past. He has a particular interest in the area’s rich architectural history.