James J. Husband, designed county courthouse before being chased from Cleveland in shame

While several architects have achieved lasting fame in Cleveland as a tribute to their skills and imagination, one architect made himself so notorious that he was forced to leave the city on a few minutes notice, never to return.

His name was James J. Husband, a native of Virginia who first worked in Cleveland in the 1850s. He began work as an architect in Philadelphia where he lived from 1844 until his arrival in Cleveland in 1853.

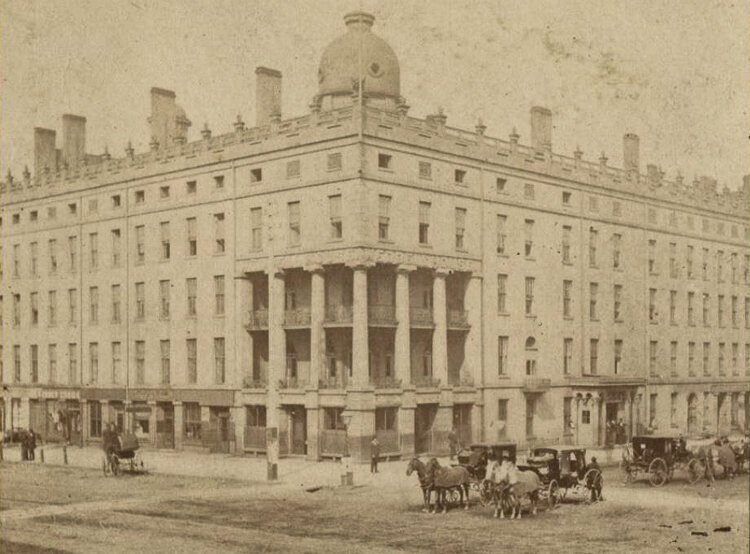

By 1860 his residence was listed as the Weddell House, a renowned 19th Century Cleveland hotel once located a Superior Avenue and West 6th Street, on the site of the present-day Rockefeller Building.

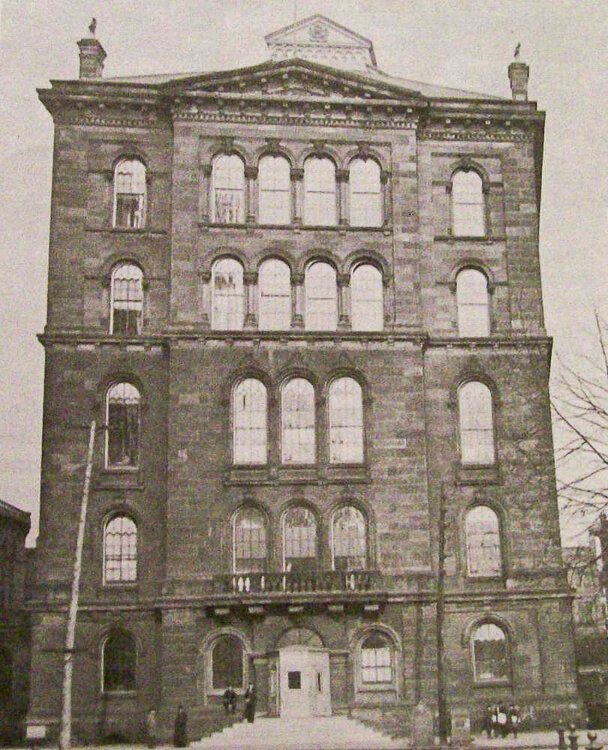

Third Cuyahoga County Courthouse once located on the northwest corner of Public Square, served as courthouse from its completion in 1858 until 1875.Husband’s output in Cleveland was small—he designed just four known buildings. One of his most memorable designs was the third Cuyahoga County Courthouse, once located on the northwest side of Public Square, just west of the Old Stone Church. Completed in 1858, the building remained in use until 1935 when it was demolished.

Third Cuyahoga County Courthouse once located on the northwest corner of Public Square, served as courthouse from its completion in 1858 until 1875.Husband’s output in Cleveland was small—he designed just four known buildings. One of his most memorable designs was the third Cuyahoga County Courthouse, once located on the northwest side of Public Square, just west of the Old Stone Church. Completed in 1858, the building remained in use until 1935 when it was demolished.

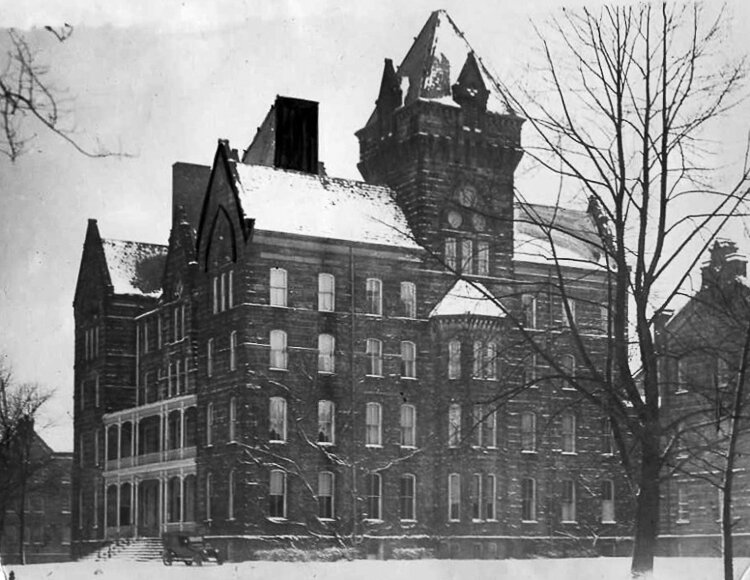

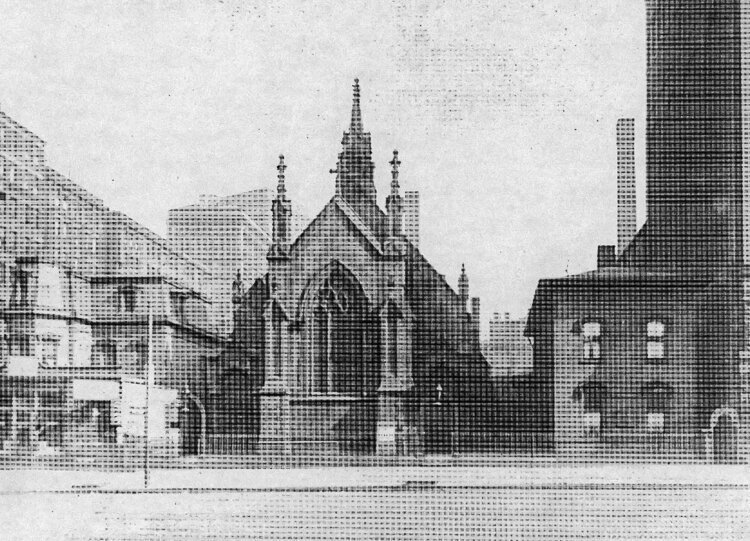

The other three buildings Husband completed in Cleveland include the 1853 Euclid Street Presbyterian Church, 1420 Euclid Ave.; the 1852 Northern Ohio Lunatic Asylum (Husband also designed the Southern Ohio Lunatic Asylum in Dayton that same year); and the 1854 Trinity Church, 520 Superior Ave. All of these structures have been demolished, according to the Cleveland Landmarks Commission.

As a southerner living in a northern city Husband’s political views were not in complete alignment with his Cleveland neighbors. This was destined to be his downfall when President Abraham Lincoln was assassinated.

In April 1865 Robert E. Lee surrendered his Army of Northern Virginia to Ulysses S. Grant at Appomattox. This signaled the collapse of the Confederate Army and effectively ended the Civil War after four years of bloody conflict.

This news met with great celebration in Cleveland. The surrender took place on Palm Sunday, April 9, 1865. Just five days later as President Lincoln watched a performance of “Our American Cousin” at Ford’s Theater in Washington, D.C. on April 14, a gunshot rang out, mortally wounding the president.

Carried across the street to a boarding house, physicians in attendance pronounced Lincoln’s case hopeless. He died without regaining consciousness at 7:22 a.m. the next day.

When the news reached Cleveland, rejoicing turned to grief. In this climate James Husband took it upon himself to express pleasure at Lincoln’s death, saying that it was overdue and represented a small loss.

To say Husband’s contemporaries sharply disagreed with his opinion would be a considerable understatement.

Trinity Church - 520 Superior AvenueA mob immediate formed in Cleveland, and it was soon clear that Husband’s life was in danger. At one point he was actually placed in a jail cell for his own safety. The mob did not relent, and Husband barely escaped serious injury.

Trinity Church - 520 Superior AvenueA mob immediate formed in Cleveland, and it was soon clear that Husband’s life was in danger. At one point he was actually placed in a jail cell for his own safety. The mob did not relent, and Husband barely escaped serious injury.

Husband fled Cleveland, never to return. He turned up in Baltimore, Maryland where city directories list him as an architect as late as the early 1890s.

Just days after Husband was run out of town, Abraham Lincoln paid a final visit. A considerable outpouring of grief accompanied his lying in state on Public Square, a stop on the itinerary of the funeral train carrying his body home to Springfield Illinois.

Thousands of Clevelanders stood patiently in line in a gentle rain in order to have a last glimpse of the face of Abraham Lincoln.

As for James Husband, Cleveland wasn’t quite done with him. The courthouse he designed had a cornerstone listing the Cuyahoga County Board of Commissioners and identifying Husband as the building’s architect.

After Husband’s outburst, a stonecutter was engaged to remove his name. This explains the narrow rectangular horizontal line that may be seen on the cornerstone to this day at the Western Reserve Historical Society, where it serves as a silent witness to one of the darkest days in American history and a rash statement that Clevelanders found unforgivable.

About the Author: Tom Matowitz

Recently retired after a 37-year career teaching public speaking, Tom Matowitz has had a lifelong interest in local and regional history. Working as a freelance author for the past 20 years he has written a number of books and articles about Cleveland’s past. He has a particular interest in the area’s rich architectural history.