Knox & Elliot: From the Hippodrome to the Rockefeller, they designed memorable Cleveland buildings

Active in Cleveland from 1893 to 1925, the firm of Knox & Elliot was responsible for several of Cleveland’s best remembered buildings.

The firm’s background was quite unusual. Senior partner William Knox was born in Scotland in 1858 and did not arrive in the United States until 1886. Finding work in the Chicago office of Burnham and Root, he met John H. Elliot who was a native of Canada.

The two men formed a partnership in 1888 in Toronto, Elliot’s home town. They were responsible for the design of several important buildings there, returning to Chicago in 1893 to take part in design work for the buildings of the World’s Columbian Exposition there. After designs tasks were completed, Knox and Elliot moved to Cleveland where they specialized in commercial buildings.

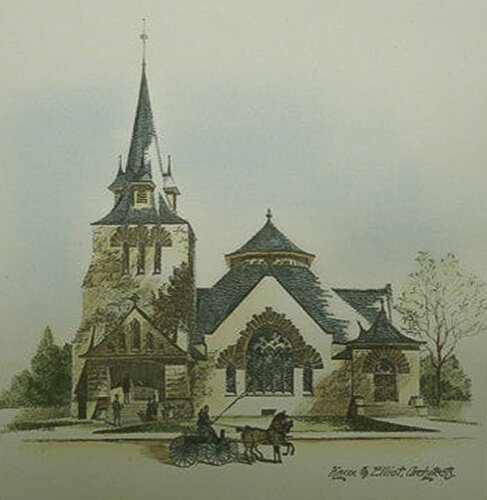

Trinity Congregational Church 1896 - From the American Architect and Building News, June 6, 1896.An important exception was their 1894 Trinity Congregational Church, which achieved fame in the 20th Century as St. James African Methodist Episcopal (AME) Church at 8401 Cedar Ave. in the Fairfax neighborhood.

Trinity Congregational Church 1896 - From the American Architect and Building News, June 6, 1896.An important exception was their 1894 Trinity Congregational Church, which achieved fame in the 20th Century as St. James African Methodist Episcopal (AME) Church at 8401 Cedar Ave. in the Fairfax neighborhood.

Purchased for $57,500 from its original congregation in 1926, the church immediately began serving as a beacon for civil rights. The church was substantially damaged by fire in 1938 and rebuilt. Another fire in 1950 required major repairs not completed until 1953. The building is an example of Richardsonian Romanesque style. St. James AME Church serves a large and stable congregation to this day.

Two of Knox & Elliot’s best-known commercial buildings include the Rockefeller Building and the Hippodrome Theater. Additionally, Knox and Eliot are remembered for the Standard Building at 99 W. St. Clair Ave. and the Engineers Building (formally known as the Brotherhood of Locomotive Engineers Building) on St. Clair Avenue and Ontario Street.

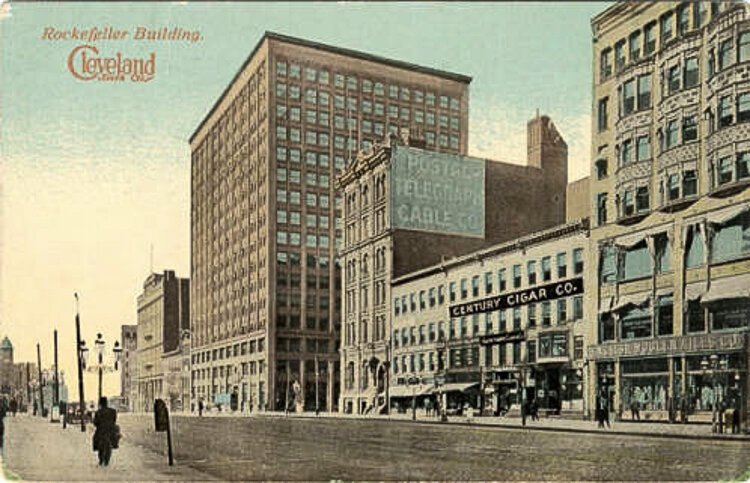

The Rockefeller Building in 1910, erected by John D. Rockefeller in 1903-05.The Rockefeller Building is regarded as Knox & Elliot’s finest work in Cleveland. Constructed between 1903 and 1905 at W.6th and Superior Avenue, the structure took the place of Weddell House—one of Cleveland’s best known 19th Century hotels, and the scene of speech from a balcony delivered by Abraham Lincoln on his way to Washington in 1861.

The Rockefeller Building in 1910, erected by John D. Rockefeller in 1903-05.The Rockefeller Building is regarded as Knox & Elliot’s finest work in Cleveland. Constructed between 1903 and 1905 at W.6th and Superior Avenue, the structure took the place of Weddell House—one of Cleveland’s best known 19th Century hotels, and the scene of speech from a balcony delivered by Abraham Lincoln on his way to Washington in 1861.

The influence of Chicago on Knox & Elliot is apparent in the Rockefeller, which has many elements in common with the work of architect Louis Sullivan, whose other acolytes included a young Frank Lloyd Wright.

The influence of Burnham & Root also is evident in the Rockefeller—demonstrated by the intricate decoration of its lower stories and the clean soaring lines of its tower.

The building was sold in 1920. The new owner, businessman Josiah Kirby, not surprisingly renamed his purchase, calling it the Kirby Building. This displeased John D. Rockefeller to such an extent that he reacquired the building in 1923 in order to restore the original name, which it has borne ever since.

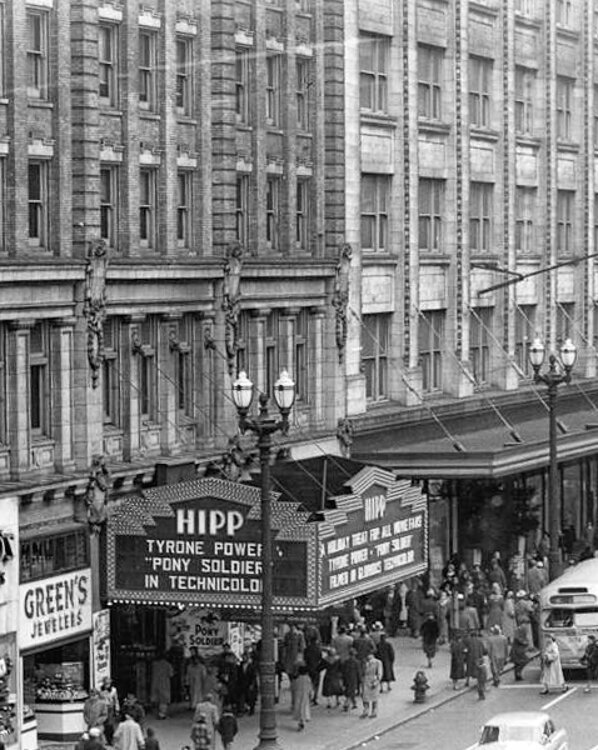

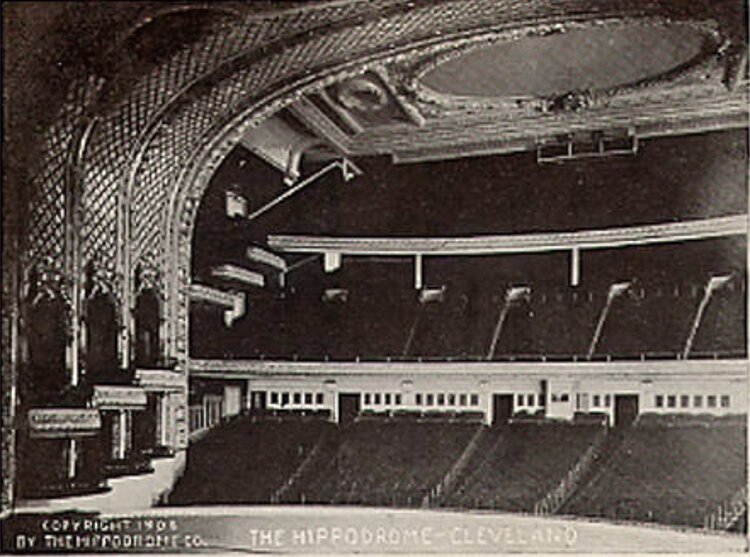

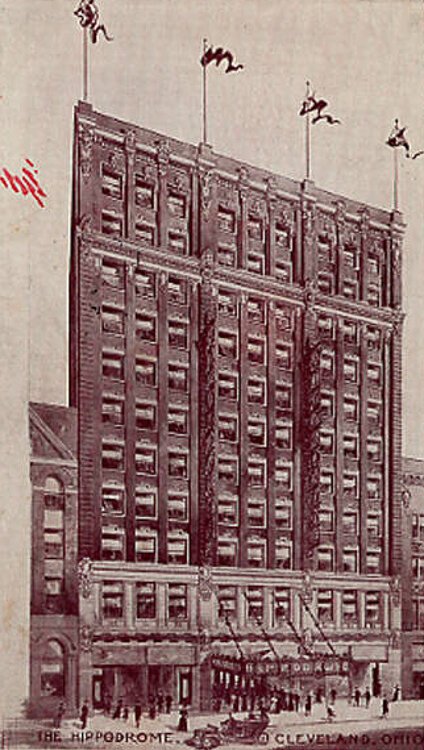

Knox & Elliot designed the Hippodrome Theater in an 11-story office building at 720 Euclid Avenue. It opened in December 1907 and was one of Cleveland’s largest theaters—the largest theater in Ohio at the time—seating 4,500 patrons.

It was a venue for everything from vaudeville to opera, with silent films thrown in for good measure. Performers there included Sarah Bernhardt, W. C. Fields, Will Rogers, and Al Jolson.

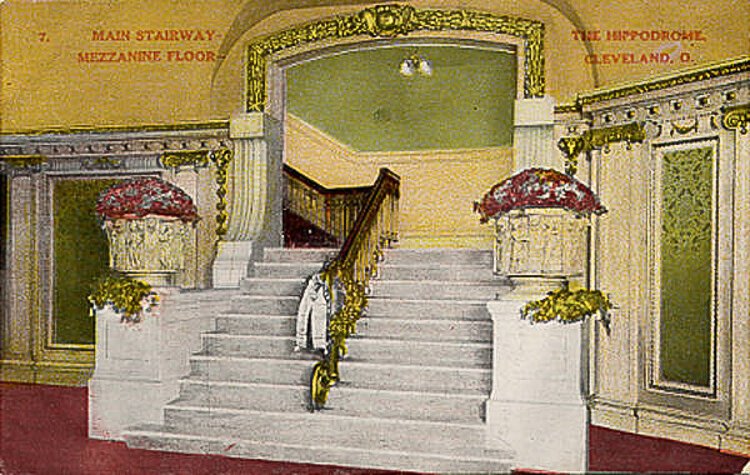

The interiors were known for their sumptuous decoration. It was no wonder. The theater cost $2 million to build.

The Hippodrome Theater old postcardThis magnificent building fell victim to the same trends responsible for the demise of so many other downtown landmarks. Suburban movie theaters siphoned away the Hippodrome’s audience, and by the mid-1970s the business offices on the upper floors had lost their tenants.

The Hippodrome Theater old postcardThis magnificent building fell victim to the same trends responsible for the demise of so many other downtown landmarks. Suburban movie theaters siphoned away the Hippodrome’s audience, and by the mid-1970s the business offices on the upper floors had lost their tenants.

In 1981 Hippodrome owner Elmer J. Babin made the difficult decision to sell the property.

Babin was quoted in a “Plain Dealer” article saying that he would like to see the property renovated, but that he found the building’s basic operating costs untenable—having paid an $86,000 heating bill the previous winter.

The building was sold to developers who made demolition their first order of business. In a familiar scenario, the land it sat on had become more valuable than the structure itself.

The stage that once echoed to the music of John Philip Sousa and the distinctive voice of Al Jolson was replaced by a parking lot.

Knox & Elliot’s 1924 Standard Building, described by Robert C. Gaede in his “Guide To Cleveland Architecture” as an Art Deco confection, began life as the Brotherhood of Locomotive Engineers Bank Building. It survives today as a high-end apartment building.

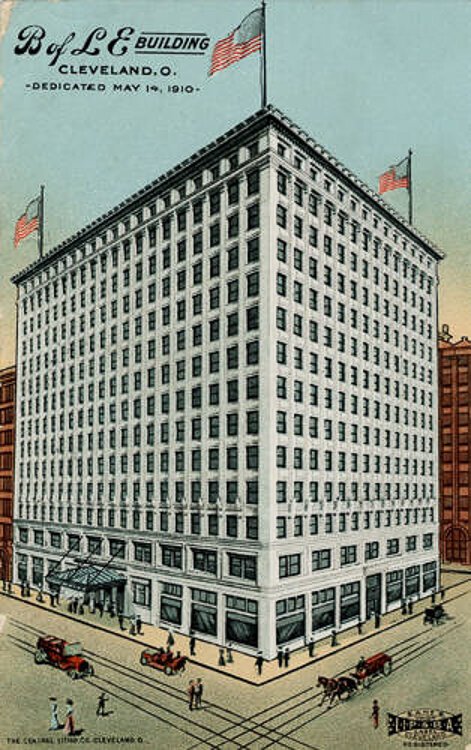

The Engineers Building is another highly regarded Knox & Elliot building that no longer exists. Notable as the first major office building in the country owned by a labor union, construction began in March 1909 and was completed a little more than a year later in May 1910 at a cost of $1.4 million.

The Engineers Building was designated a Cleveland Landmark in March 1977, but the designation failed to protect it a decade later when it came to the notice of developers, who demolished the building 1989—much to the continued regret of Cleveland preservationists.

The site is now occupied by the Cleveland Marriott at Key Tower.

After William Knox died in 1915, John Elliot carried on until his own death 10 years later, bringing the era of Knox & Eliot to a close.

About the Author: Tom Matowitz

Recently retired after a 37-year career teaching public speaking, Tom Matowitz has had a lifelong interest in local and regional history. Working as a freelance author for the past 20 years he has written a number of books and articles about Cleveland’s past. He has a particular interest in the area’s rich architectural history.