League Park: A large piece of Cleveland sports history

Cleveland been home to a variety of professional sports teams extending back to the 19th Century. A remarkable reminder of those early days stands at the northeast corner of East 66th Street and Lexington Avenue in the Hough neighborhood.

For 130 years League Park has hosted a variety of teams—from professional baseball to college football—and today stands as a tribute to days gone by and home to the Baseball Heritage Museum.

Frank Robison owned the Cleveland Spiders, a National League team best remembered for signing future Hall of Fame pitcher Cy Young.

League Park

League Park

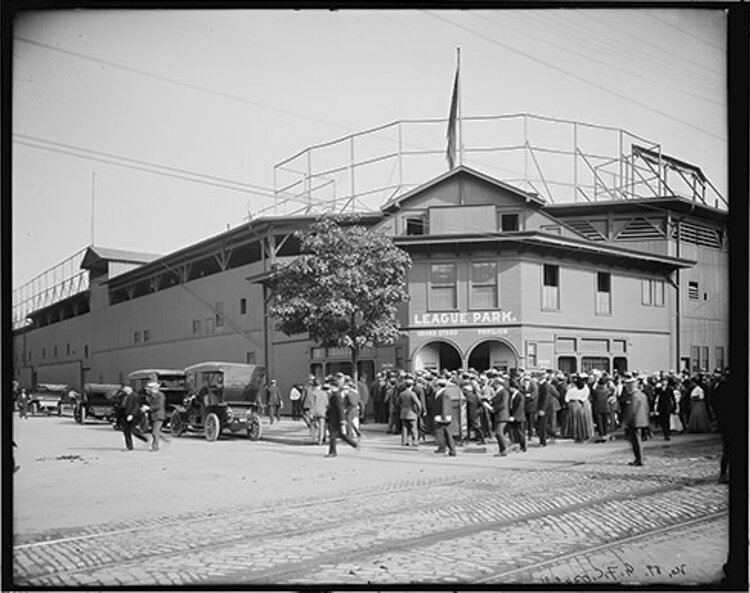

Robison chose League Park’s location because the site was along the route of his Payne Avenue streetcar line at East 66th Street and Lexington Avenue and he wanted to increase ridership and attendance at the games.

The first game in League Park was played on May 1, 1891, with a 12-1 victory over the Cincinnati Reds with Cy Young throwing the first pitch. The team’s performance was often uneven, leading to a disastrous 1899 season that saw the Spiders win 20 games while losing 134—to this day the worst record in Major League Baseball history.

Attendance suffered accordingly, with an average of 145 spectators attending games in a stadium that seated 9,000. The 1899 season caused the demise of the Spiders and a new baseball team wasn’t known as the Indians until 1915.

The park survived the dismal attendance and went on to host a number of other teams whose records proved more exciting. The Cleveland Indians—first known as the Bluestockings, or Blues for short, and as the Naps, to honor player Napoleon Lajoie—played in League Park from 1901 until 1932, and again from 1934 to 1946.

The Indians won the 1920 World Series against the Brooklyn Dodgers, playing the last four games of the series at League Park. The series included 10 future Hall of Farmers—including Stan Coveleski, Joe Sewell, Tris Speaker, Rube Marquard, Zack Wheat, and Burleigh Grimes—and those games remain one of the finest hours in Cleveland sports.

In the fifth game of the 1920 World Series at League Park, Indians second baseman Bill Wambsganss made the only unassisted triple play in World Series history.

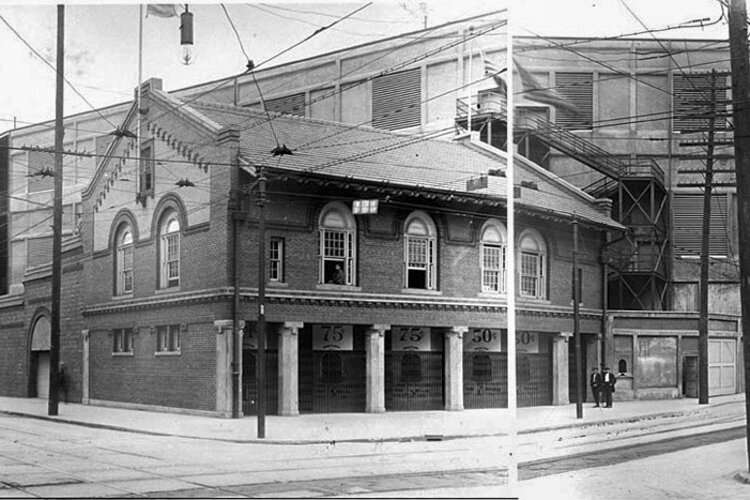

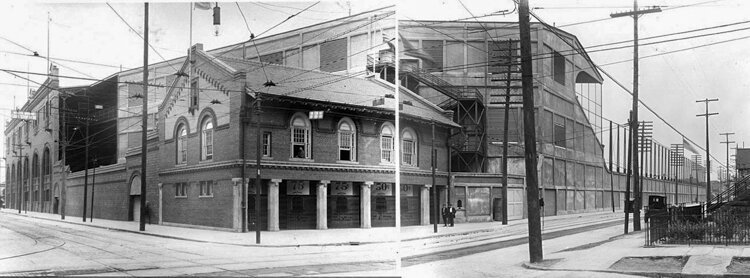

The park itself underwent a major transition during this time, with the original wooden structure dating from 1891 being replaced with a modern steel and concrete structure in 1910, with Osborn Engineering Company (still in existence today) being responsible for the redesign.

The opening of Cleveland Municipal Stadium in 1932 strongly impacted League Park’s future. Centrally located and far more accessible by car, the new stadium hosted Indians weekend games while League Park remained in use for weekday games until 1946.

In this time, in 1941, New York Yankee center fielder Joe DiMaggio went on a 56-game hitting streak—a record that has not been broken to this day. DiMaggio's streak ended on July 17,1941 when the Yankees played the Indians in League Park.

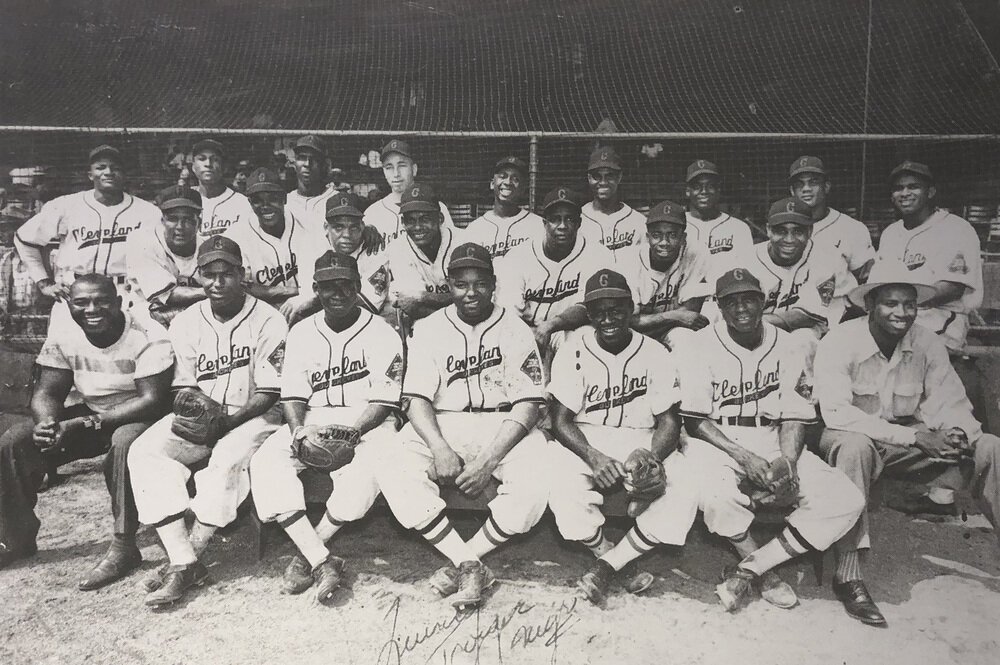

The Cleveland Buckeyes of the Negro American League called League Park home in the late 1940s and established a winning record while playing there.

League Park also hosted college football games for years, with Western Reserve University Red Cats playing its home games there from 1929 to 1949 there, with a break of several years in the early 1940s, most likely due to World War II.

The Cleveland Rams of the NFL played at League Park in 1937 and for much of the early 1940s, winning a championship in 1945. Much to the distress of Cleveland football fans, their champions almost immediately left the city for Los Angeles.

Later in the 1940s the Cleveland Browns used League Park as a practice field.

Arial view of League Park

Arial view of League Park

The final athletic contest at League Park was a college football game—a shut out played on November 24, 1949, with Western Reserve University defeating the Case Institute of Technology 30-0.

Most of the park was demolished in 1951. After a half century of neglect, increased interest has led to the restoration of the 1909 office building with a museum and a replica of the baseball field on the site.

On August 23, 2014, the site was rededicated and is now known as the Baseball Heritage Museum. It is also a city park named in honor of Cleveland City Council member and community activist Fannie Lewis, recognizing her long service to the community.

One hundred thirty years after the park opened, the crack of bats and the yells of excited spectators can be heard again with youth leagues and other recreational play bringing a memorable era in Cleveland sports history back to life.

About the Author: Tom Matowitz

Recently retired after a 37-year career teaching public speaking, Tom Matowitz has had a lifelong interest in local and regional history. Working as a freelance author for the past 20 years he has written a number of books and articles about Cleveland’s past. He has a particular interest in the area’s rich architectural history.