St. Paul’s Episcopal Church: A grand church on Millionaire’s Row that survived the migration east

In the late 19th Century, commerce and industry had transformed Cleveland into a bustling city of wealth and development. No longer a sleepy New England village, fortunes in business were made and resulted in an avenue acclaimed as the most beautiful street in the world—Millionaire’s Row on Euclid Avenue.

Running roughly from Erie Street (present day East 9th Street) to Willson Avenue (present day East 55th Street), Euclid Avenue’s Millionaire’s Row took its name from the procession of grand houses that lined both sides of the street.

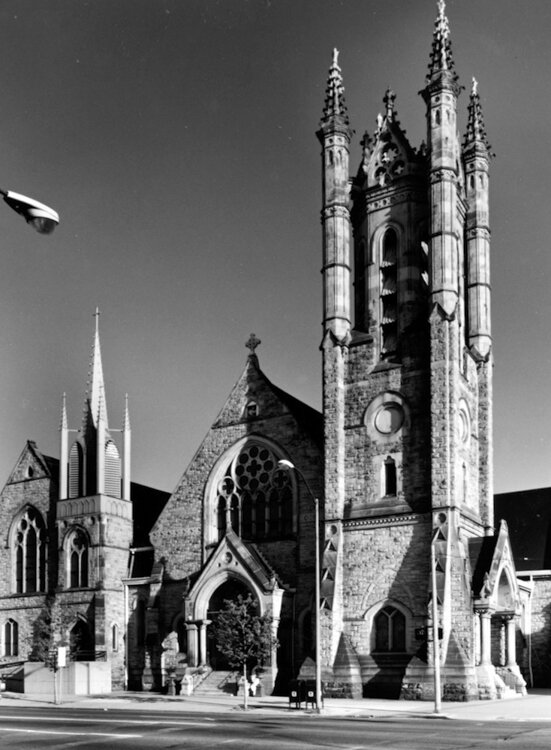

St. Paul’s, Ca. 1901: Around the turn of the last century, St. Paul's was one of more than a half-dozen large stone churches that served Cleveland's "Millionaires' Row" along Euclid Avenue.The names of the residents form a roll call of Cleveland’s wealthiest and most influential families. They were known for success in both business and politics and included Cleveland’s elite—John D. Rockefeller, John Hay, Charles F. Brush, Amasa Stone, Marcus Hanna, and Samuel Mather—to name a few.

St. Paul’s, Ca. 1901: Around the turn of the last century, St. Paul's was one of more than a half-dozen large stone churches that served Cleveland's "Millionaires' Row" along Euclid Avenue.The names of the residents form a roll call of Cleveland’s wealthiest and most influential families. They were known for success in both business and politics and included Cleveland’s elite—John D. Rockefeller, John Hay, Charles F. Brush, Amasa Stone, Marcus Hanna, and Samuel Mather—to name a few.

The heyday of this grand avenue was approximately 1870 to 1910. Changing circumstances thereafter began to erode its foundation and by the mid-20th Century it was largely gone.

Long since overtaken by commercial development, very few traces remain today.

One of the most remarkable of these traces is the former St. Paul’s Episcopal Church at the intersection of Euclid Avenue and East 40th Street.

Constructed in 1876 the Gothic Revival church was designed by Gordon W. Lloyd, a Detroit-based architect responsible for the design of several other grand churches elsewhere in Ohio.

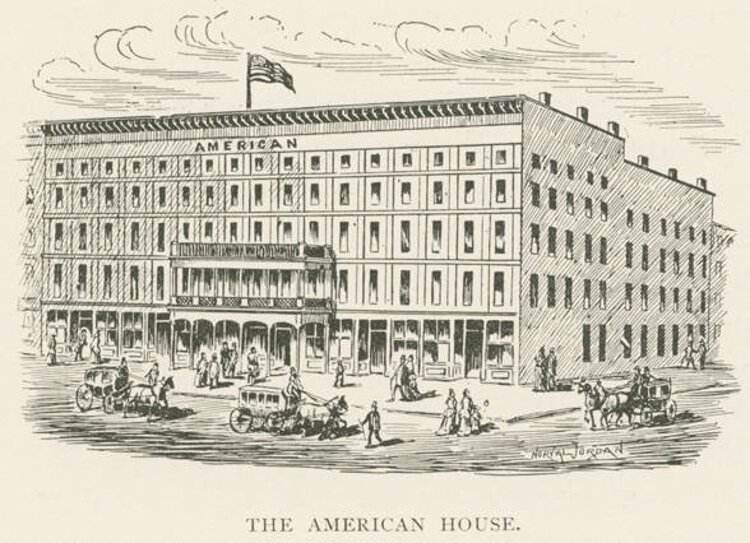

St. Paul’s church traces its background to the autumn of 1846. The congregation originally met in the American House Hotel on Superior Street and consisted of just 45 members led by rector Gideon B. Perry. After meeting in rented rooms, a new building was planned at the intersection of Euclid Avenue and Sheriff Street (present day East 4th Street). This proposed church burned before it could be occupied.

Residents from across the city donated funds to build a new church from brick. Finally completed in 1858, this building served the church until commercial development dictated a move further east—to Euclid Avenue and Case Street (present day East 40th Street) in the heart of Millionaire’s Row.

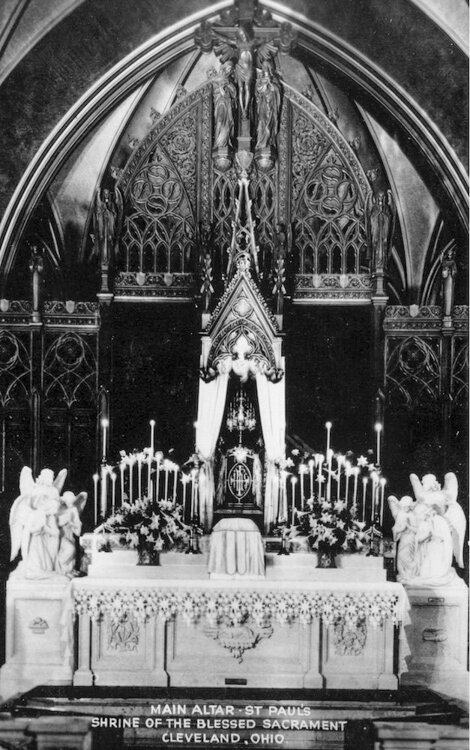

Purgatory Window: One of St. Paul Shrine's Francis Xavier Zettler windows, this unusual stained glass window depicts the mass being said as souls in purgatory await their release to Heaven.This new Victorian Gothic church made of Berea sandstone was designed by Lloyd. It was notable for a selection of beautifully executed stained-glass windows created by Louis Comfort Tiffany.

Purgatory Window: One of St. Paul Shrine's Francis Xavier Zettler windows, this unusual stained glass window depicts the mass being said as souls in purgatory await their release to Heaven.This new Victorian Gothic church made of Berea sandstone was designed by Lloyd. It was notable for a selection of beautifully executed stained-glass windows created by Louis Comfort Tiffany.

The first service in the new church was held on Christmas Eve 1876. The church could accommodate gatherings of 1,000 people and quickly become strongly identified with its wealthy neighborhood.

Over the years it was the scene of many society weddings as well as several notable funerals. At Marcus Hanna’s funeral in 1904, mourners included Theodore Roosevelt who interrupted his duties as president to travel to Cleveland to attend.

The years passed, and in the end the church bowed to a pattern that had overtaken so many others: A changing neighborhood and an encroaching commercial development prompted the congregation to move further east.

In 1928 the congregation moved to a new Walker & Weeks-designed church in Cleveland Heights, on the corner of Coventry Road and Fairmount Boulevard, and placed the old church up for sale.

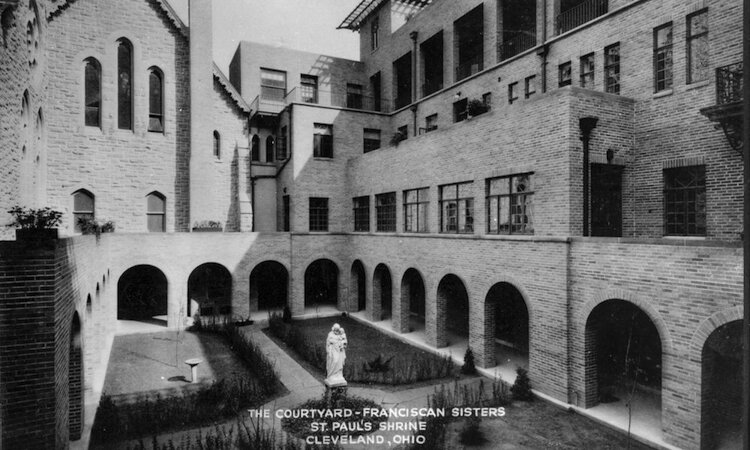

This postcard depicts the Courtyard of the Franciscan Sisters, ca. 1930sThe Catholic Diocese of Cleveland became the new owner in 1931, changing the name of the building to the Shrine of the Conversion of St. Paul. Under Catholic ownership, the facility also houses a branch of the Poor Clares, an order of contemplative nuns who have worshipped there for 90 years.

This postcard depicts the Courtyard of the Franciscan Sisters, ca. 1930sThe Catholic Diocese of Cleveland became the new owner in 1931, changing the name of the building to the Shrine of the Conversion of St. Paul. Under Catholic ownership, the facility also houses a branch of the Poor Clares, an order of contemplative nuns who have worshipped there for 90 years.

Today the building is a remarkable survivor and a direct link to a storied era in Cleveland’s now-distant past. One of the few extant buildings from Millionaire’s Row, it is the only one still serving its original purpose.

While Charles Schweinfurth’s grand house designed for Samuel Mather still stands today, it has been in the hands of various institutions for 90 years and hasn’t served as a private residence since the 1930s. Mather built the mansion on Euclid Avenue in hopes it would encourage his wealthy neighbors to stay put and stop the eastbound migration.

But it ultimately was a failed effort—Instead of saving Millionaire’s Row the construction of the Mather Mansion signaled the beginning of its downfall.

Standing just as strong and true as the day it opened in December 1876, the former St. Paul’s Episcopal Church along Millionaire’s Row continues to serve the spiritual life of its neighborhood just as those responsible for its creation intended.

About the Author: Tom Matowitz

Recently retired after a 37-year career teaching public speaking, Tom Matowitz has had a lifelong interest in local and regional history. Working as a freelance author for the past 20 years he has written a number of books and articles about Cleveland’s past. He has a particular interest in the area’s rich architectural history.