Robert P. Madison, man of many architectural, personal triumphs

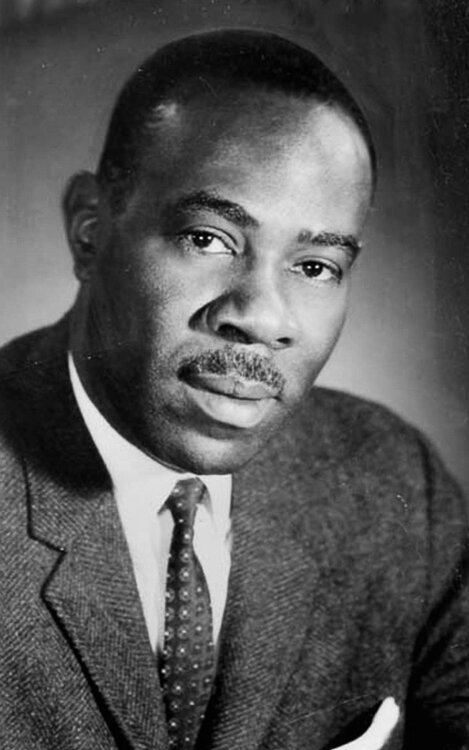

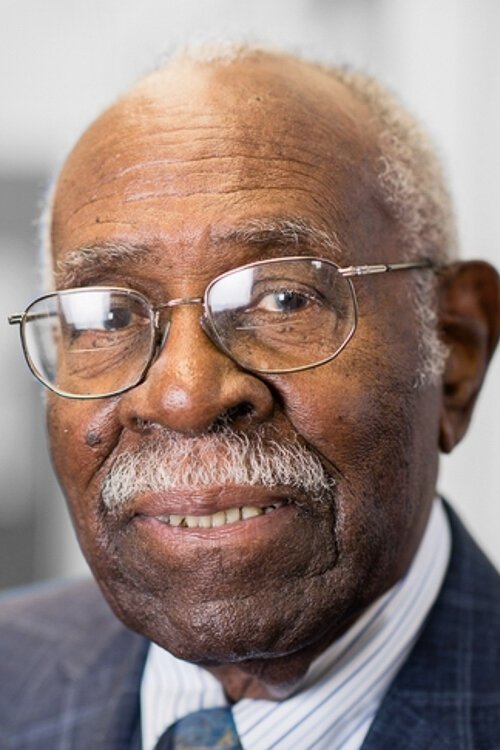

Architect and Cleveland native Robert P. Madison not only created a legacy in his architectural firm, Robert P. Madison International in downtown Cleveland, but he is also a man noted for accomplishing many firsts in his career—and today the Shaker Heights resident is the oldest living Black Architect in the United States.

Robert P. Madison reitred in 2016 after a six-decade careerBorn in Cleveland on July 23, 1923, education was strongly emphasized in the Madison household. Madison was encouraged at an early age to pursue his dream of becoming an architect—a lofty goal fraught with obstacles for an ambitious young Black man in the 1940s.

Robert P. Madison reitred in 2016 after a six-decade careerBorn in Cleveland on July 23, 1923, education was strongly emphasized in the Madison household. Madison was encouraged at an early age to pursue his dream of becoming an architect—a lofty goal fraught with obstacles for an ambitious young Black man in the 1940s.

“When I was in the first grade, I came home with a drawing that I had made at school and my mother saw the drawing and said, ‘son, you're going to be an architect,’” recalls Madison, who is today 98 years old and living in Shaker Heights. “It happens that my father was already a civil engineer, and he was a teaching at Southern University teaching engineering and related subjects like mathematics, chemistry, physics, etcetera. So that's all I have ever done. All I've ever done all my life. except for the military.”

Madison was an honors graduate of East Tech High School and began his architectural studies in 1940 at Howard University.

But in 1940 world events were about to take control, causing a major disruption in Madison’s career plans. He left school to become part of the legion of American soldiers who fought om the front lines to defeat Hitler’s Germany.

He became a First Lieutenant in the U.S. Army’s 370th Regimental Combat Team of the 92nd Infantry Division. Part of the Fifth Army in Italy, this unit played a vital role in the long-drawn-out Italian Campaign lasting from 1943 until the German surrender in May 1945.

Robert Madison and two other U.S. service members in Swiss Alps after Wold War IIMadison did not watch from a distance. As an infantry officer on the front lines, he emerged from the war with a Combat Infantryman’s Badge and a Purple Heart—recognizing a serious wound received in battle.

Robert Madison and two other U.S. service members in Swiss Alps after Wold War IIMadison did not watch from a distance. As an infantry officer on the front lines, he emerged from the war with a Combat Infantryman’s Badge and a Purple Heart—recognizing a serious wound received in battle.

“I was hit by a German 88-millimeter shell as I was driving the Jeep up in the mountains of Italy,” he recalls of the attack. “The fragments hit the jeep, where I should have been sitting [in the passenger seat] by the side of the mountain. The jeep went down the road and crashed.”

Soldiers nearby retrieved the injured Madison and took him to a field hospital. “I had shrapnel in my abdomen and in my left foot—I could hardly walk,” he says. “I was lucky because a lot of people died. But I was fortunate, I was able to recover. And I’m grateful. But it was war. I was within one inch of not being here today.”

After the war, Madison returned home to resume his long-interrupted pursuit of his dream of becoming an architect. This time he sought admission to the School of Architecture at Western Reserve University, where the dean of admissions initially rejected him because he was Black.

But Madison persisted.

“I went home, and I put out my military uniform, came back up to the school in my uniform and this time I talked to the dean of admissions, not the dean of architecture,” he recalls. “I said to him ‘my blood is over there on the soil of Italy, fighting to make this country free and I don't know why I can’t enter the School of Architecture.’ The dean of admissions said, ‘well, Madison, we’ll see what we can do.’”

Yet Madison still had to prove himself to gain admission. “They gave me an examination every Saturday from June until September to see if I was even literate—you know, I was transferring from Howard University before the war, which was the Harvard University of Black people,” he says. “They finally asked me to take these tests I passed them all and therefore I was admitted to the school.”

Yet Madison still had to prove himself to gain admission. “They gave me an examination every Saturday from June until September to see if I was even literate—you know, I was transferring from Howard University before the war, which was the Harvard University of Black people,” he says. “They finally asked me to take these tests I passed them all and therefore I was admitted to the school.”

Madison became the first African American to earn an architectural degree in the state of Ohio and the first Black graduate of the Western Reserve University School of Architecture in 1948. He then went to Harvard University Graduate School of Design and studied under renowned architect Walter Gropius, earning a master’s degree in 1951.

Madison completed his education at the Ecole des Beaux Arts in Paris, achieving the same level of training sought by predecessors like J. Milton Dyer and Abram Garfield at the turn of the 20th Century. He also holds an honorary doctorate from Howard University, conferred in 1987.

Armed with these impressive credentials he then entered a new fight, one for success and recognition in a profession from which his race had been largely excluded.

Architecture is a profession that builds things—builds houses, office buildings, universities—the whole concept is about designing to build buildings,” Madison says. “So, I always say that when I studied architecture my objective was to become a very good architect—no matter what kinds of buildings we were doing."

That philosophy worked in Madison’s favor when he struggled to launch his career—taking almost any job that came to him.

“When I started out, nobody really wanted to hire me because they never heard of a Black architect,” he recalls. “I got things like remodeling back porches and remodeling houses for people.”

He says he’ll never forget his very first job after completing his education: “It was the back porch of the house that was falling down,” Madison laughs. “And these people wanted somebody to repair it. That's what they actually started with.”

Things were not easy for a Black architect in the days when Madison was just launching his career. “When I started practicing architecture, people thought it some kind of a joke that because they have never heard of an architect of color,” he says.

But Madison easily proved himself, and his talents, and not only built a successful career, but he also crossed racial boundaries at the time.

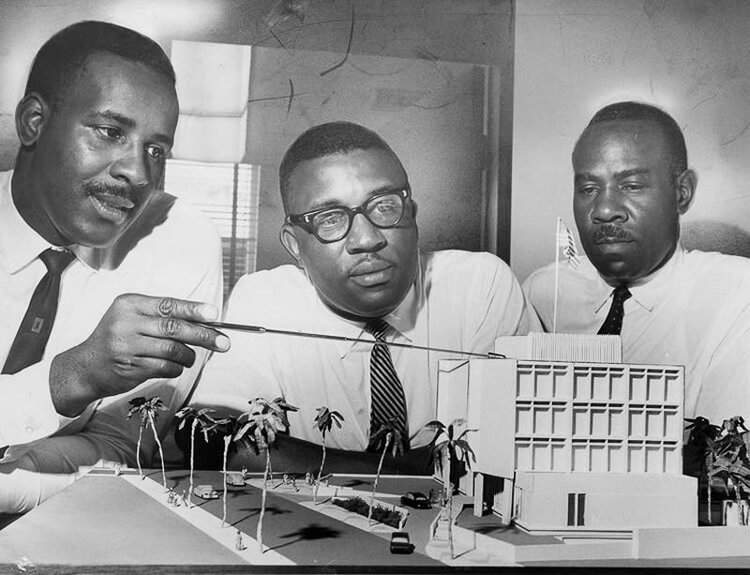

Park Place Apartments“I’m actually really proud of this: My firm was the first firm to be absolutely interracial,” he says. “We hired Black people, white people, Chinese people, Indian people from India, the Russians. We really had a multicultural firm working for us because that was what we had to do. As a result, the work we did was really fascinating.”

Park Place Apartments“I’m actually really proud of this: My firm was the first firm to be absolutely interracial,” he says. “We hired Black people, white people, Chinese people, Indian people from India, the Russians. We really had a multicultural firm working for us because that was what we had to do. As a result, the work we did was really fascinating.”

After his first jobs repairing porches, Madison then entered two house designs in an Ohio architectural competition. “I think there were 250 people who submitted, and I won third prize and an honorable mention,” he recalls.

“From that point on, people say, ‘well you know he won all those competitions, and he came in third and honorable mention and that's pretty good.’ That was when I really got established.”

In 1949 Madison began a marriage to Leatrice Lucille Branch that was destined to last more than 60 years and in 1954 he launched Robert P. Madison International with his brothers, becoming the first Black-owned architecture firm in Ohio.

Madison’s first building project came in 1959 with the Mt. Pleasant Medical Center on Kinsman Avenue, which won an architectural design award. “That’s when they said, ‘well, this guy’s for real,’” he quips.

When the medical center was torn down, Madison was commissioned to design a multi-story County office building on the same site. But Madison says his favorite local project was the Fatima Family Center on Lexington Avenue and East 65th Street in Hough.

When the medical center was torn down, Madison was commissioned to design a multi-story County office building on the same site. But Madison says his favorite local project was the Fatima Family Center on Lexington Avenue and East 65th Street in Hough.

“I think it's my favorite because of what it does for the community,” says Madison. “This building attracts young people in the community, and it teaches them to become better citizens. I feel so strongly about being able to contribute positively, and this is a first class building with everything you would want there. I feel good about that.”

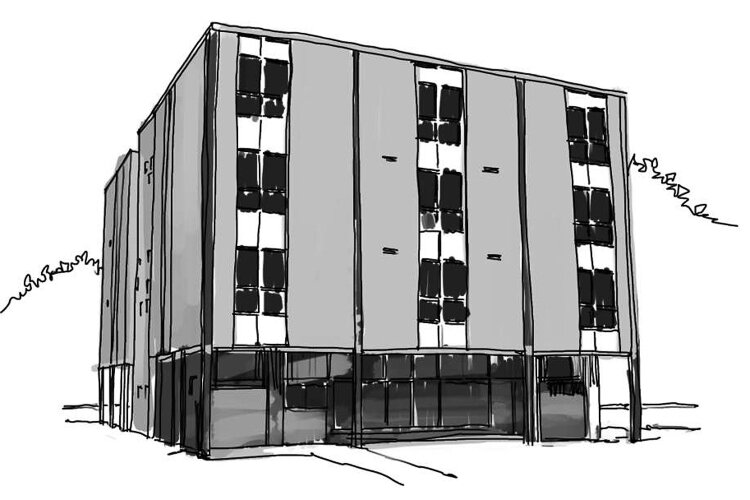

But he is also proud of Park Place Apartments, which he designed in 1969 and got creative with materials to create a unique look.

“I think there were about 85 apartments, and the material was very simple because it was public housing—concrete block and steel—and we tried to develop new forms to make it have some degree of desirability,” he says. “I liked that project, it had quite a bit of structure. It was fun.”

Madison says the project came when Carl Stokes became mayor of Cleveland. “There was sort of an opening for people to address some of the needs of people who lived in Cleveland, who were primarily African Americans,” he recalls. “And we could do that because I knew about the structures that were going on elsewhere.”

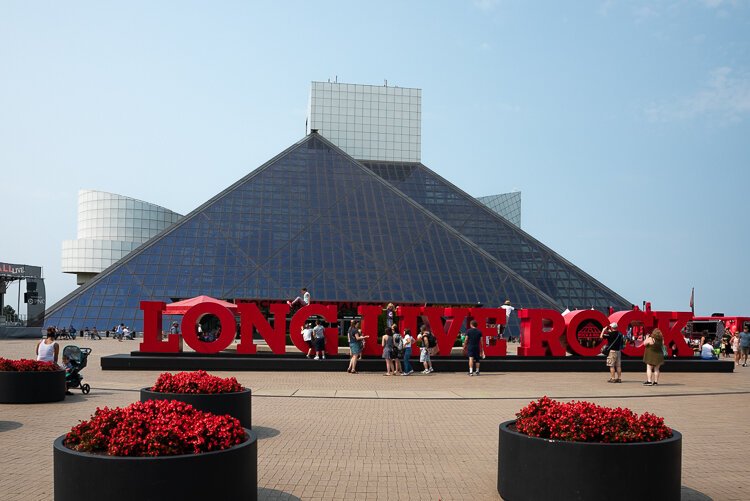

First Energy StadiumOther projects Madison is proud of include the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame, where he worked as an associate architect on the project with I.M. Pei; the interior renovation of the Stokes Wing at the Cleveland Public Library; the State of Ohio Computer Center in Columbus; the 1979 Frank J. Lausche State Office Building on Superior Avenue and East 6th Street; and as associate architect on Cleveland Browns Stadium (now First Energy Stadium), among many other projects.

First Energy StadiumOther projects Madison is proud of include the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame, where he worked as an associate architect on the project with I.M. Pei; the interior renovation of the Stokes Wing at the Cleveland Public Library; the State of Ohio Computer Center in Columbus; the 1979 Frank J. Lausche State Office Building on Superior Avenue and East 6th Street; and as associate architect on Cleveland Browns Stadium (now First Energy Stadium), among many other projects.

Success came in the form of awards for domestic architecture as well as his 1965 design for the U.S. Embassy in Dakar, Senegal in West Africa.

Madison cites architectural giants like Charles-Édouard Jeanneret (aka Le Corbusier), Ludwig Mies van der Rohe, Walter Gropius, and Frank Lloyd Wright, as some of the men he’s admired throughout his career.

“At that time, this was just after Second World War, there was great amount of searching for identity, searching for form, and there were new [ideas forming],” he says. “It was about establishing the best modernity we could with the resources we had. Because we didn’t have an unlimited budget, we had to stretch whatever budget we had to the limit, and that’s what we did. I’m very proud of that.”

Madison’s work has been recognized with the AIA Ohio Gold Medal Firm Award in 1994 and the Cleveland Arts Prize in 2000.

When asked if there is any one project he would do differently, Madison is quick to answer: “My house—the houses I designed back in 1960 I would design differently,” he says.

Madison and his family lived in Cleveland at the time, and he and Leatrice wanted to move to the Heights so their daughters could get a good education. He and his friend Charlies DeLeon—a psychiatrist and professor at Western Reserve University—were both looking for homes, but at the time, no one in Cleveland Heights or Shaker Heights would sell a home to a Black family.

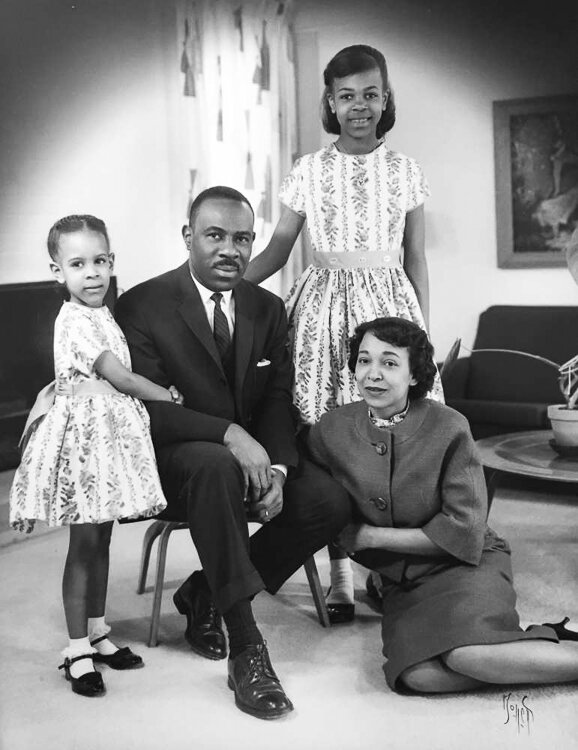

Robert and Leatrice Madison, with daughters Juliette and Jeanne, circa 1963“On the telephone, people thought that [DeLeon] was a Spanish, but he was actually an African-American,” Madison recalls. “[It was] the same with me—when I’d show up it was different, and when he’d show up, they were like ‘no, no.’”

Robert and Leatrice Madison, with daughters Juliette and Jeanne, circa 1963“On the telephone, people thought that [DeLeon] was a Spanish, but he was actually an African-American,” Madison recalls. “[It was] the same with me—when I’d show up it was different, and when he’d show up, they were like ‘no, no.’”

Madison reports that both Leatrice and DeLeon’s wife found properties on North Park Boulevard and Delaware that they liked. “No one would sell us existing houses,” he recalls. “So, we had some friends buy the lots for us, because we couldn’t buy them, and they quit claimed the deeds to us. And we began to build houses at North Park Boulevard and Delaware Drive in Shaker Heights—two houses. I designed those houses in 1960 and I had to design the houses understanding what the building committee would accept.”

Madison says they had to forego design elements to make sure the homes were within the city guidelines. “It was a house that we did under great pressure but what we wanted was a place for our children to go to school, not a place to show our personalities,” he says. “If I had a chance to do it again it would be totally different. But back in those days we took the circumstances we had and did the best we could.”

The designs were perfectly competent. “Those houses are still there, and people bought them,” Madison says. “And they liked them.”

He admits he conformed to what he knew Shaker would approve. “If I did it over, I would build with more glass, more exposure to the sun and to the wind, to take advantage of the atmosphere in which you live, with trees and growth,” Madison says. “But I’m going back 67 years, and that’s a long time and a lot has changed.”

Madison retired in 2016 at the age of 93 and after six decades leading his firm. He left his niece Sandra Madison in charge of Robert P. Madison International. She now runs the firm with her husband, R. Kevin Madison (Robert Madison’s nephew), and Robert Klann, and it is the largest Black female-owned architecture firm in Ohio.

“Oh. they were very big shoes to fill,” Sandra says of taking over. “Robert, he stepped back gradually. He’d come in maybe two times a week, then he’d come in twice a month, and he’d always say, ‘how are you guys doing?’ He’d always step in, but he was always there to answer any questions we had. He did it over a year, but then he did step away.”

Since Sandra has taken over, the firm has headed several large projects—including work with area school districts and most recently the Karamu House renovations. The first two phases have been completed, and the firm has moved into the third and final phase.

Since Sandra has taken over, the firm has headed several large projects—including work with area school districts and most recently the Karamu House renovations. The first two phases have been completed, and the firm has moved into the third and final phase.

“I love working on it just because of its long history,” says Sandra of the Karamu project.

While things may have changed since the mid- and late 20th Century, Sandra says racism in the architecture industry has gotten better, but not entirely. “It’s not as overt,” she says. “I think in the last year things have gotten better, they are changing. The whole Black Lives Matter movement affects so many industries. I can see it changing in all walks of life, but nothing changes overnight.

"It has to be intentional, and we all have to be intentional about trying to make change a reality," she continues. "I want to see it where it’s not something you even think about. It should be something that’s just natural.”

In July Robert Madison will turn 99 years old.

He says he is proud of Sandra, Kevin, and Robert and the legacy they are continuing. “I’m happy that my firm can move on, and I don’t know of any other firm of my peers that has carried on like this,” he says. “I feel strongly about what we’ve achieved and what we continue to achieve. I’m proud. It wasn’t easy, but when I think back about it, we did do some good things. We emerged because we were professionals. We emerged because we were very good, and we worked at it.”

About the Author: Karin Connelly Rice Karin Connelly Rice enjoys telling people's stories, whether it's a promising startup or a life's passion. Over the past 20 years she has reported on the local business community for publications such as Inside Business and Cleveland Magazine. She was editor of the Rocky River/Lakewood edition of In the Neighborhood and was a reporter and photographer for the Amherst News-Times. At Fresh Water she enjoys telling the stories of Clevelanders who are shaping and embracing the business and research climate in Cleveland.

About the Author: Tom Matowitz

Recently retired after a 37-year career teaching public speaking, Tom Matowitz has had a lifelong interest in local and regional history. Working as a freelance author for the past 20 years he has written a number of books and articles about Cleveland’s past. He has a particular interest in the area’s rich architectural history.