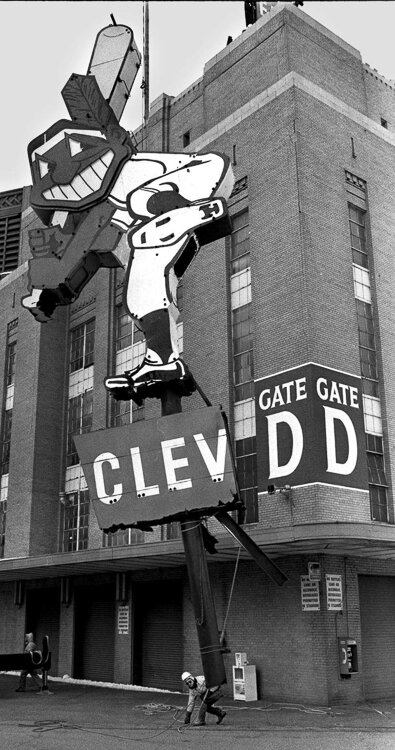

Cleveland Municipal Stadium: An iconic lakefront memory for Cleveland sports and music fans

Many buildings once familiar to generations of Clevelanders exist today only in memory. High on this list would be Cleveland Municipal Stadium, a fixture on the city’s lakefront from 1931 until its demolition 65 years later.

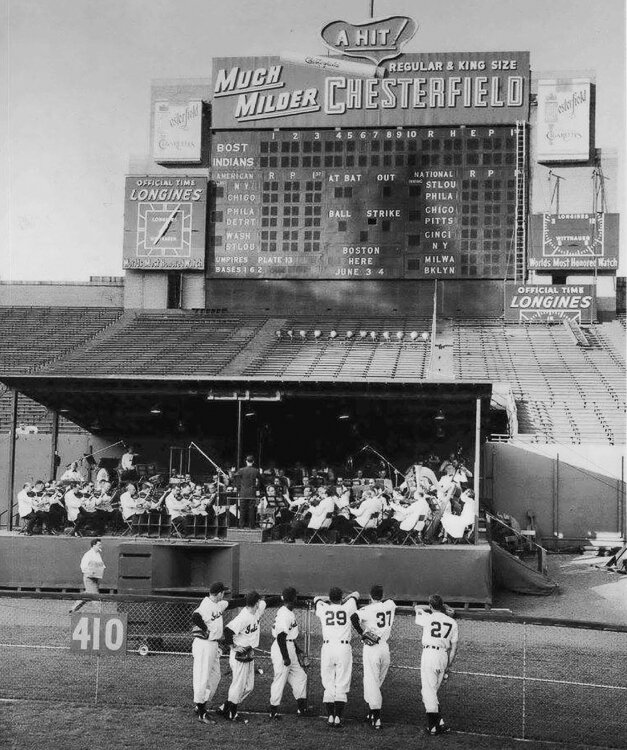

Cleveland Summer Orchestra at the first "Indipops" in the Municipal Stadium in 1953.The Stadium saw its share of triumphs—ranging from the Cleveland Rams victory over the Washington Redskins to win the NFL Championship in 1945, to the Cleveland Indians victory in the 1948 World Series, to the 1964 NFL Championship game that saw the Cleveland Browns shut out the Baltimore Colts 27-0.

Cleveland Summer Orchestra at the first "Indipops" in the Municipal Stadium in 1953.The Stadium saw its share of triumphs—ranging from the Cleveland Rams victory over the Washington Redskins to win the NFL Championship in 1945, to the Cleveland Indians victory in the 1948 World Series, to the 1964 NFL Championship game that saw the Cleveland Browns shut out the Baltimore Colts 27-0.

Unfortunately, the stadium also saw a good number of infamous disasters—the Red Right 88 play in a windy 1981 NFL playoff game against the Oakland Raiders and The Drive during the 1986 AFC Championship game against the Denver Broncos in January 1987—that both further contributed to the angst of local fans who had by then gone decades without a championship team.

The Stadium also hosted boxing matches, religious gatherings, and never-to-be-forgotten rock concerts—from The Beatles and Aretha Franklin to Pink Floyd and Michael Jackson.

Today’s Clevelanders typically remember the structure in its decline in the 1980s and 90s. To fully understand its importance to the city it is necessary to go back to the 1920s.

Cleveland’s early sports venue was League Park at East 66th Street and Lexington Avenue. As automobiles became more common, parking became an issue in the Hough neighborhood.

A site on the lakefront was chosen on land that didn’t exist a few years earlier. It was based on a landfill. Planning for the new stadium began in the mid-1920s.

Architecturally, the new stadium had an impeccable pedigree. It was constructed by Osborn Engineering and based upon a design prepared by renowned Cleveland architects Walker & Weeks.

Osborn Engineering was an excellent choice. Not only was the firm also involved with League Park, Osborn built New York’s Yankee Stadium, Chicago’s Comiskey Park, Boston’s Fenway Park, and a number of other sports venues across the country.

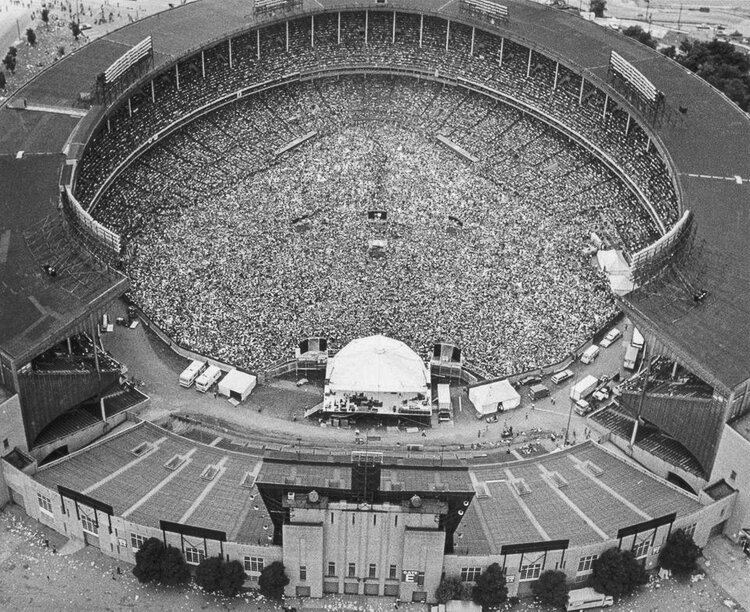

1964 NFL Championship Game, The Browns vs the Baltimore Colts

1964 NFL Championship Game, The Browns vs the Baltimore Colts

Municipal Stadium was completed in 1931 and hosted its first event on July 3—a boxing match between Max Schmeling and Young Stribling. Schmeling successfully defended his heavyweight championship. Ticket prices ranged from $3 to $25, and spectators witnessed Schmeling knocking down Stribling in the 15th round. The referee stopped the fight, declaring Schmeling the victor.

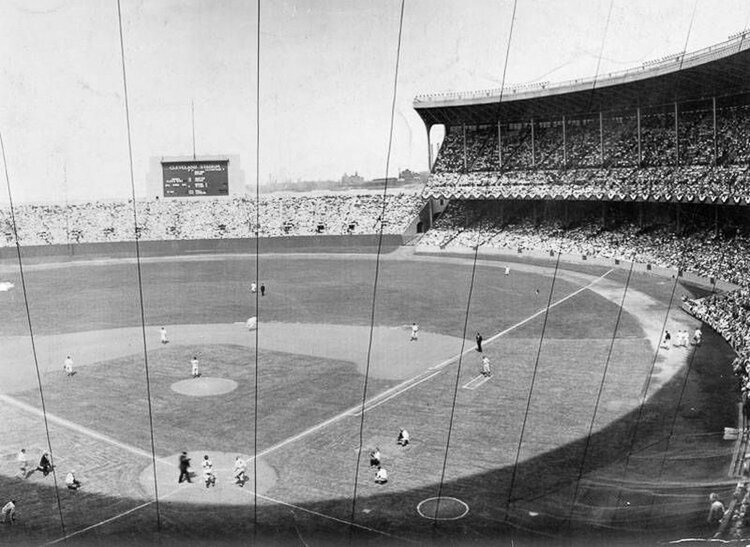

The Cleveland Indians first game in the new stadium was played in July 1932. For 15 years Indians games were divided between the Municipal Stadium and League Park until 1947 when the Indians abandoned the old ball field.

An early triumph at the stadium was the 1945 Cleveland Rams NFL Championship. Cleveland football fans weren’t given much time to savor this victory, as the team almost immediately announced a move to Los Angeles to become the first professional football team to play on the west coast. A disappointed wag among the crestfallen fans referred to the departed team as the “Cleveland Scrams.”

The disappointment proved temporary as the new Cleveland Browns began what proved to be a 50-year tenure at the lakefront stadium in 1946. Coached by the legendary Paul Brown, the team quickly became a powerhouse—winning multiple championships in the 40s and 50s.

The stadium provided the largest seating capacity of any outdoor venue in the world at the time, with seats for 78,189 spectators. This capacity was severely taxed in September 1935 when the stadium hosted the Seventh National Eucharistic Congress. A midnight mass drew 125,000 to the stadium (originally schedule to be at Public Hall)—the single largest crowd in the stadium’s history

Arguably the stadium’s finest hour came in 1948 with the Indians World Series victory over the Boston Braves, four games to two. It touched off a celebration unrivaled until the Cavaliers NBA Championship victory against the Golden State Warriors 68 years later in 2016 (although the Cleveland Browns 1964 Championship victory against the Baltimore Colts came close).

Unfortunately, 1964 marked the beginning of a very long drought for Cleveland professional sports.

Cleveland Municipal Stadium soldiered on, providing a familiar venue for multitudes of devoted Cleveland sports fans.

Music lovers were not overlooked at Municipal Stadium, as the World Series of Rock—an annual daylong rock festival from 1966 to 1980—brought many of the most renowned music acts of a generation to the stadium.

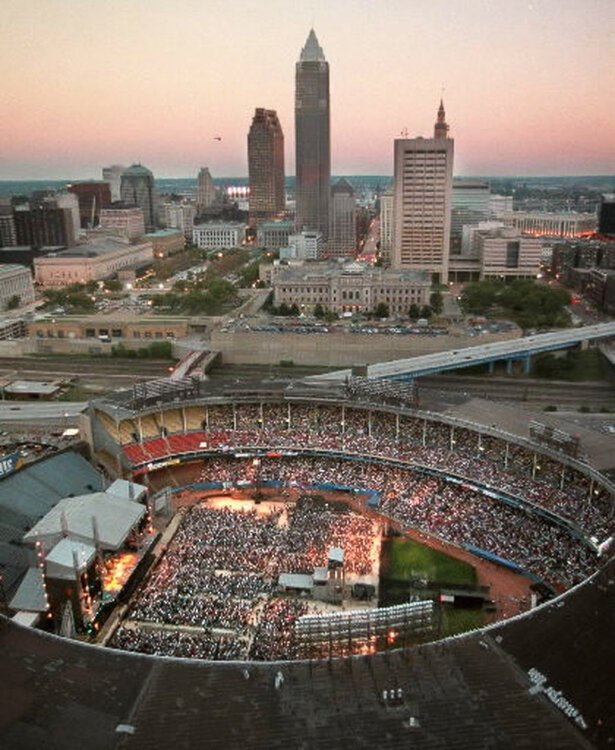

Cleveland Municipal Stadium during the concert for the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame and Museum on Sept. 2, 1995A notable event for the stadium in this era occurred on May 15, 1981. Indians pitcher Len Barker pitched a perfect game against the Toronto Blue Jays, defeating the visitors 3-0. Barker never allowed a single runner on base and struck out 11 batters. This was only the 10th perfect game in MLB history.

Cleveland Municipal Stadium during the concert for the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame and Museum on Sept. 2, 1995A notable event for the stadium in this era occurred on May 15, 1981. Indians pitcher Len Barker pitched a perfect game against the Toronto Blue Jays, defeating the visitors 3-0. Barker never allowed a single runner on base and struck out 11 batters. This was only the 10th perfect game in MLB history.

By the early 80s the stadium was really showing its age. Leased by Browns owner Art Modell for many years, long deferred maintenance issues caught up with the building in the early 1990s. Unable to reach an agreement with the city, Modell in November 1995 announced that he was moving the Browns to Baltimore where the team would be known as the Ravens.

The Indians had departed for Jacobs Field, leaving the old stadium without a resident team. This spelled the end of Cleveland Municipal Stadium and plans to demolish it were announced.

With a certain irony, Osborn Engineering, the company that took pride in building the structure in the 1930s, oversaw its demolition.

By March 1, 1997, Cleveland Municipal Stadium was gone—existing only in the memory of loyal fans who cheered on the Browns and the Indians there for two generations.

About the Author: Tom Matowitz

Recently retired after a 37-year career teaching public speaking, Tom Matowitz has had a lifelong interest in local and regional history. Working as a freelance author for the past 20 years he has written a number of books and articles about Cleveland’s past. He has a particular interest in the area’s rich architectural history.