Arthur Oviatt: Designed upscale summer getaways for local wealthy entrepreneurs

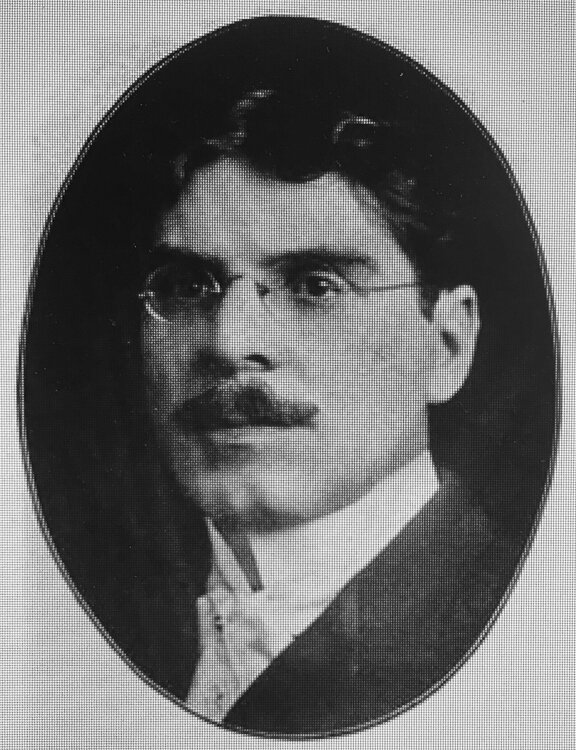

Arthur OviattArthur N. Oviatt, a Northeast Ohio native, was a self-educated architect, studying in several Cleveland architectural offices before gaining a measure of renown as the designer of several of elaborate summer homes for wealthy Cleveland businessmen.

Arthur OviattArthur N. Oviatt, a Northeast Ohio native, was a self-educated architect, studying in several Cleveland architectural offices before gaining a measure of renown as the designer of several of elaborate summer homes for wealthy Cleveland businessmen.

Born in North Dover, Ohio and a graduate of Lakewood High School, Oviatt worked as a draftsman with Hardway & Williams from 1889 to 1891 before opening his own practice.

Oviatt worked on projects with Frank Lloyd Wright and Charles Schweinfurth, and even completed a handwritten Ohio Architect and Builder index for the Cleveland Public Library that can still be found at the main branch in the fine arts department.

The Lake Shore Electric Interurbans at the Cleveland Railway Company's streetcar yards on Detroit Ave. in western LakewoodOviatt’s period of greatest activity was at the turn of the 20th Century, when he built his reputation designing upscale summer homes for wealthy young entrepreneurs. In particular, he designed homes in Lake County for those who made their fortunes on the interurban railroad system, which saw its heyday in the 30-year span between 1895 and 1925.

The Lake Shore Electric Interurbans at the Cleveland Railway Company's streetcar yards on Detroit Ave. in western LakewoodOviatt’s period of greatest activity was at the turn of the 20th Century, when he built his reputation designing upscale summer homes for wealthy young entrepreneurs. In particular, he designed homes in Lake County for those who made their fortunes on the interurban railroad system, which saw its heyday in the 30-year span between 1895 and 1925.

Oviatt’s clients and summer neighbors—Edward W. Moore, Henry Everett, and Horace Andrews—were prime examples of the wealth the system generated. These men were associated with the Cleveland, Painesville & Eastern and the Lakeshore Electric interurban lines, which connected to other lines that permitted efficient long-distance travel.

Moore and Everett created a syndicate that gave them a controlling interest in a large network of innovative interurban lines at the height of their popularity. Powered by electricity, railroads didn’t require the heavy infrastructure needed by their steam powered counterparts. They were found across the country, and enabled passengers to travel at high speed and great comfort.

Edward MooreBurgeoning fortunes in the days before federal income tax made it possible for wealthy young entrepreneurs to hire Oviatt to help them escape Cleveland and regain the pastoral scenes of their youth in Lake County—if only for summer weekends before returning to their downtown offices to make more money.

Edward MooreBurgeoning fortunes in the days before federal income tax made it possible for wealthy young entrepreneurs to hire Oviatt to help them escape Cleveland and regain the pastoral scenes of their youth in Lake County—if only for summer weekends before returning to their downtown offices to make more money.

Oviatt designed three important houses in Lake County in the late 1890s. His designs had a distinctive style. They tended to be large frame structures with a front door crowned by a pediment supported by columns and flanked by a pair of small oval windows. The homes were also known for the rich detail in their exterior decoration and vivid color schemes. Oviatt was not in favor of overall coats of white paint.

Oviatt’s summer houses succumbed to changing times as much as anything else. Only a handful of his houses remain in in Mentor, Bratenahl, and Cleveland. Knowledgeable observers can easily recognize his style.

In the late 1800s, on adjoining properties in Mentor, Oviatt built houses for Andrews and Moore. Andrews’ house was called Primrose Hill and stood on a bluff overlooking a beautiful expanse of lawn.

Half a mile away, and sited further south, stood Moore’s estate, Mooreland. A short distance further west in Willoughby stood a new house for Henry Everett. All this activity took place around 1897 and 1898.

Nothing lasts forever, and the glory of these houses and their owners was destined to be brief.

Choosing the wrong side in a dispute over street car fares, Andrews left Cleveland for New York City before World War I. His former home was purchased around 1914 by banker and Oglebay Norton partner David Z. Norton and Primrose Hill was thereafter known as Nortonwood.

The house Arthur Oviatt designed for Henry Everett. This is the building that burned and was replaced by the Frank Meade designed house that is now the Kirtland Country Club.Everett’s Oviatt-designed house was destroyed by fire sometime before 1909. Frank Meade designed a stone replacement house for Everett to take the place of the earlier Oviatt design. Everett died in 1917 and his heirs sold the Meade-designed house to the organizers of the Kirtland Country Club in the early 1920s.

The house Arthur Oviatt designed for Henry Everett. This is the building that burned and was replaced by the Frank Meade designed house that is now the Kirtland Country Club.Everett’s Oviatt-designed house was destroyed by fire sometime before 1909. Frank Meade designed a stone replacement house for Everett to take the place of the earlier Oviatt design. Everett died in 1917 and his heirs sold the Meade-designed house to the organizers of the Kirtland Country Club in the early 1920s.

In the summer of 1975, the Club building met with disaster. A violent thunderstorm caused a lightning strike that set the house ablaze. Despite the diligent efforts of several local fire departments, it was damaged so badly that in almost any other context it would have been considered a total loss.

Club members refused to accept this, and a careful restoration was undertaken. This proved to be a great success, but much of the character of the original structure was inevitably lost.

The fate reserved for Mooreland was almost worse. The great irony is that while Moore famously declared that private cars would not threaten his interurban empire—on the grounds that the good roads necessary to make them practical would never be built—in the end that is precisely what happened.

Within a generation of Moore’s death in the spring of 1928, traffic on I-90 just a few hundred yards away filled his formerly idyllic summer house with the sound of cars.

In 1967 what remained of Moore’s former property was sold to newly created Lakeland Community College. This was under the condition that Moore’s eldest daughter, Margaret Moore Clark, could live in the house undisturbed for the rest of her life.

The building had been extensively modified by J. Milton Dyer in 1906 and 1907. It was otherwise unchanged until Clark’s own death in 1982.

The house then entered a dark age—standing empty and neglected for the best part of decade. In 1989 a well-intentioned effort to save the house began. It was supplanted by a clumsy restoration in the mid-1990s that deliberately destroyed much of the house’s original character.

Within 60 years of its construction, Horace Andrews’ house was torn down, and the two survivors had seen extensive changes. While the Kirtland Country Club rose from the ashes to regain its status as a showplace, Mooreland is an entirely different matter. Showing obvious signs of neglect and surrounded by an unkempt and overgrown lawn, its future again looks uncertain.

Oviatt lived a long life, dying in retirement in Florida in 1960. Late in life he declared that houses like the ones he designed at the turn of the 20th Century would be sources of inspiration to future generations.

One is left to wonder what he would make of the fates that have overtaken them.

About the Author: Tom Matowitz

Recently retired after a 37-year career teaching public speaking, Tom Matowitz has had a lifelong interest in local and regional history. Working as a freelance author for the past 20 years he has written a number of books and articles about Cleveland’s past. He has a particular interest in the area’s rich architectural history.