Charles A. Platt: Designer of many Playhouse Square buildings, grand William Gwinn Mather estate

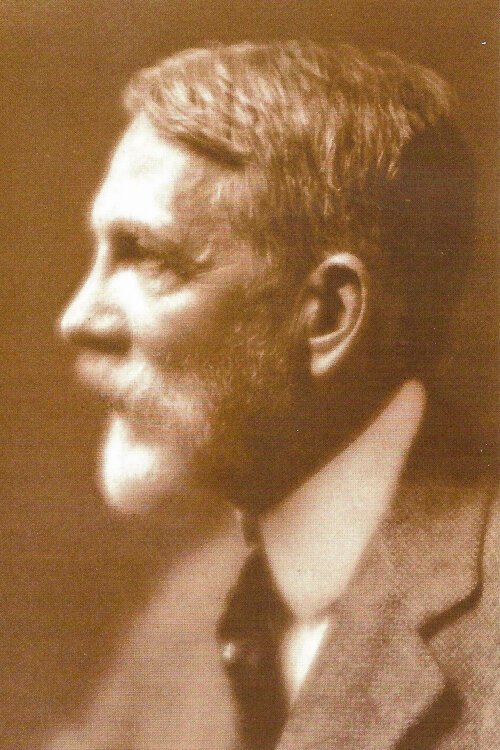

Charles A. Platt was a native New Yorker and a true renaissance man, renowned as an artist, an author, and an architect. Although he divided his time between New York City and New Hampshire, he was often called to Cleveland to design buildings and homes that still stand today.

His early notice came through his work as a painter and etcher, for which he had extensive formal training before his interest turned to architecture.

Platt’s training as an artist began at the age of 19 when he trained as a landscape painter and etcher as an apprentice in 1880 under Stephen Parrish in Gloucester, Massachusetts. He later studied art in Paris, where he exhibited paintings and etchings at the 1885 Paris Salon—giving Platt his first exposure to a wide audience.

Charles A. PlattShortly after his Paris break, Platt endured a level of personal tragedy that would have stopped many people in their tracks. In the span of 11 months in 1886 and 1887, he lost his father, his father-in-law, his new wife Ellen Corbin Hoe, and the newborn twin daughters she died giving birth to.

Charles A. PlattShortly after his Paris break, Platt endured a level of personal tragedy that would have stopped many people in their tracks. In the span of 11 months in 1886 and 1887, he lost his father, his father-in-law, his new wife Ellen Corbin Hoe, and the newborn twin daughters she died giving birth to.

At the time of these tragic events, Platt was just 26 years old, but he somehow recovered and continued his work. In 1893 he remarried Eleanor Hardy Bunker and they went on to have five children—two of them sons who followed their father’s footsteps to become architects.

A trip to Italy in 1892 to document surviving Renaissance villas and gardens sparked his interest in architecture. Platt studied at the National Academy of Design in New York as well as the Academie Julian in Paris to earn his certification as an architect.

By the turn of the 20th Century Platt’s career as an architect was established and he went on to design homes to Cleveland’s wealthy business leaders and several notable buildings in Playhouse Square.

One remarkable residential project occurred when Platt was commissioned to design the 1907 Gwinn Estate in Bratenahl—the stunning home of Cleveland business leader William G. Mather.

Mather led Cleveland Cliffs—creating one of the most successful iron ore trade firms—from his father’s death in 1890 until the 1940s. He was renowned for his generosity to the Cleveland Museum of Art, which reflected Mather’s strong personal interest in the arts. He was a benefactor who also served in important leadership roles culminating in a 16-year term as the museum’s president from 1933 to 1949.

Mr. William G. Mather standing amid his famed gardens at the Gwinn designed by Warren H. Manning in 1941.Platt engaged his outstanding contemporary, Warren Manning to do Gwinn’s landscape design in collaboration with Ellen Biddle Shipman, widely acclaimed as one of the greatest landscape architects of her generation.

Mr. William G. Mather standing amid his famed gardens at the Gwinn designed by Warren H. Manning in 1941.Platt engaged his outstanding contemporary, Warren Manning to do Gwinn’s landscape design in collaboration with Ellen Biddle Shipman, widely acclaimed as one of the greatest landscape architects of her generation.

Incidentally, Shipman’s career began after encouragement from Platt, who saw early examples of landscape designs and he encouraged her to continue.

The collaboration on the Gwinn estate produced what is arguably the finest private residence ever constructed in Cleveland. Instead of the Colonial Revival and Tudor designs in vogue at the time, Platt opted for a Classical motif.

With Manning’s guidance Platt selected a dramatic site on a bluff overlooking Lake Erie. Shipman contributed memorable flower gardens that were instrumental in a landscape design said to be every bit as striking as the house itself.

Mather lived a long life. He was 50 years old when he moved into Gwinn in 1907 and he lived in the house for 44 years until his death in 1951. After sharing the house with his sister for many years he married for the first time, at age 71, to his neighbor Elizabeth Ring Mather.

Upon her death in 1957 it was arranged that Gwinn would be made available to area nonprofit organizations as a venue for meetings and social gatherings.

The house was sold into private hands in 2007 and is no longer accessible to the public. After a recent renovation it was offered for sale at $6.5 million—one of the highest asking prices ever sought for a Cleveland area residential property.

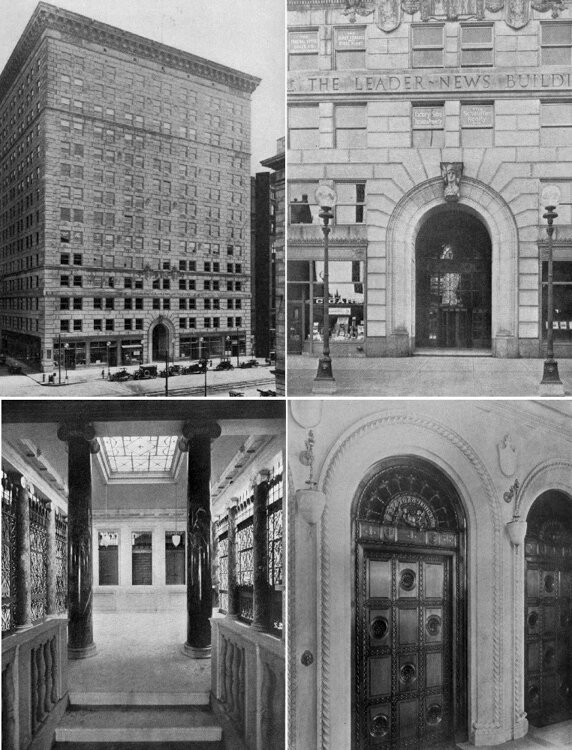

Hanna building as seen from across Euclid Avenue in 1924 shortly after the office building was completed.Working with Dan R. Hanna and his family, Platt is responsible for the designs of several notable buildings in Cleveland, including the Hanna Building, the Hanna Theater, the Leader Building.

Hanna building as seen from across Euclid Avenue in 1924 shortly after the office building was completed.Working with Dan R. Hanna and his family, Platt is responsible for the designs of several notable buildings in Cleveland, including the Hanna Building, the Hanna Theater, the Leader Building.

The 15-story Beaux Arts style Leader Building is clad in limestone and originally provided office space for the Cleveland Leader, a newspaper acquired by building owner, Dan Hanna.

Upon its completion in 1913, the Leader was the largest office building in Cleveland. The building took the place of the first Trinity Episcopal Cathedral which had occupied the site since 1854.

In 1917 the newspaper ceased publication. It’s place in the building was taken by the Cleveland News, another Cleveland paper owned by Hanna. The Leader Building has always been notable for the quality of its decoration—including marble walls in a distinctive lobby as well as bronze elevator doors ascribed to Tiffany.

The Leader underwent a renovation completed in 2017. The top 12 floors have been converted to apartments while the first three floors provide retail and office space.

The 1921 designs of the Hanna Building and Hanna Theater mark his final designs in Cleveland.

The Hanna Building was constructed in Playhouse Square and completed in 1921. The 16-story building was added to the National Register of Historic Places in 1978. The building remains in use as offices for many high-end Cleveland businesses today, while the annex was renovated and transformed into apartments several years ago.

The Hanna Theater opened on March 28, 1921—a bitter cold day in Cleveland. The first play performed was a production of an adaptation of Mark Twain’s novel, “The Prince and the Pauper.”

Hanna Theater - Photo Bob PerkoskiThe Hanna Theater played a major role in the restoration of Playhouse Square. After a long interval of neglect the Theater was refurbished and remains in use.

Hanna Theater - Photo Bob PerkoskiThe Hanna Theater played a major role in the restoration of Playhouse Square. After a long interval of neglect the Theater was refurbished and remains in use.

The theater remained in operation until 1989. After a long hiatus, the venue reopened as a cabaret theatre, with tables and chairs replacing the conventional rows of theatre seating. Since 2008 it has been the home of the Great Lakes Theater Festival.

Dan R. Hanna found little time to enjoy any of this. He died at his estate in Ossining, New York in November 1921—just short of his 55th birthday. He is buried in Lake View Cemetery.

The creative genius behind several of Cleveland’s most memorable early 20th Century buildings, Charles Platt lived for a dozen years after completing the Hanna designs. He died at his longtime summer home in Cornish, New Hampshire in September 1933 at the age of 72.

About the Author: Tom Matowitz

Recently retired after a 37-year career teaching public speaking, Tom Matowitz has had a lifelong interest in local and regional history. Working as a freelance author for the past 20 years he has written a number of books and articles about Cleveland’s past. He has a particular interest in the area’s rich architectural history.