George B. Post and Francis Millet: An architect and an artist created timeless beauty

At the turn of the 20th Century circumstances brought two major figures together to collaborate on one of Cleveland’s most recognizable buildings. George B. Post and Francis D. Millet had well-deserved national reputations and Cleveland is fortunate to have an example of their finest works. Post designed two notable Cleveland buildings, while Millet, an artist, painted murals in several Cleveland landmarks.

The Cleveland Trust rotunda at the intersection of East 9th Street and Euclid Avenue survives to this day, and Post’s earlier Williamson Building on Public Square was part of Cleveland’s daily life for more than three quarters of a century.

The Williamson BuildingGeorge B. Post was one of America’s most influential architects for an entire generation. Born in Manhattan in 1837, Post earned a degree in civil engineering from New York University in 1858. He then found employment in the office of renowned New York architect Richard Morris Hunt, who was recognized as one of America’s finest architects and is best remembered for his design of the Biltmore House—a chateau in Asheville, North Carolina that was designed for George Vanderbilt in the early 1890s and remains America’s largest private house to this day.

The Williamson BuildingGeorge B. Post was one of America’s most influential architects for an entire generation. Born in Manhattan in 1837, Post earned a degree in civil engineering from New York University in 1858. He then found employment in the office of renowned New York architect Richard Morris Hunt, who was recognized as one of America’s finest architects and is best remembered for his design of the Biltmore House—a chateau in Asheville, North Carolina that was designed for George Vanderbilt in the early 1890s and remains America’s largest private house to this day.

Post remained with Hunt for two years before opening his own established his own firm in 1867 in New York. He also maintained offices in Cleveland from 1907 to 1929.

Shortly after his time with Hunt, Post found his career interrupted by the onset of the Civil War. As a young officer in the Army of the Potomac he was among the traumatized survivors of the battle of Fredericksburg, Virginia. For two days in December 1862, 12,000 Union soldiers were killed or wounded in a series of doomed frontal attacks against Confederate infantry entrenched behind a stone wall on Marye’s Heights. This event stands as one of the war’s worst disasters for the Union.

A significant event in Post’s life was his marriage in October 1863 to Alice Matilda Stone. They had five children and two of their sons joined Post’s firm in the early 20th Century. The marriage lasted 46 years, ending with the death of Alice in 1909.

Post became well known for his designs of both elaborate private homes for the very wealthy and substantial office buildings. Post’s designs were highly regarded, and he was acclaimed as a true renaissance man—having strong ties to the arts community and deftly incorporating many different skills and decorative techniques in his buildings

Unfortunately, his buildings have a low survival rate since rising property values frequently made the land they stood on irresistible to developers.

Post was responsible for the design of two important buildings in Cleveland, the 1900 Williamson Building on Public Square and the 1903 Cleveland Trust Company building’s rotunda at the corner of East 9th Street and Euclid Avenue.

For eight decades the Williamson Building stood on the southeast corner of Public square. It was built on the site of a previous Williamson Building built in the 1880s that had been damaged by fire. This earlier building stood on the site of the Williamson house, the last private residence on Public Square.

The Post-designed Williamson Building was the tallest in Cleveland, at 17 floors, when it opened on April 1,1900, taking this honor from its neighbor across the square, the 1890 Burnham & Root-designed Society For Savings Building, which was only 10 stories.

The Williamson Building and the Cuyahoga Building were demolished in 1982 to make room for the proposed Sohio skyscraper.The Williamson Building stood shoulder to shoulder with the 1902 Cuyahoga Building, also designed by Burnham & Root. The loss of both buildings in 1982 to make way for the Sohio Building is still regretted.

The Williamson Building and the Cuyahoga Building were demolished in 1982 to make room for the proposed Sohio skyscraper.The Williamson Building stood shoulder to shoulder with the 1902 Cuyahoga Building, also designed by Burnham & Root. The loss of both buildings in 1982 to make way for the Sohio Building is still regretted.

Several blocks away stands Post’s 1907 Cleveland Trust Company Building, one of Cleveland’s most significant commercial buildings.

Cleveland Trust was founded in 1894. It is noteworthy as one of the first banks in Cleveland to offer service at branch locations (as opposed to offering services only at the main branch). After several years in rented offices, the bank decided to proceed with plans for a permanent headquarters.

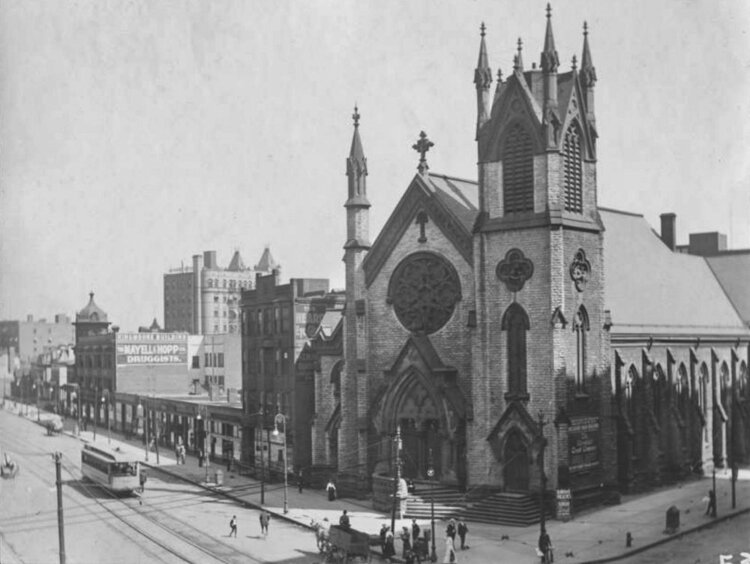

The location chosen was the former site of the First United Methodist Church on the southeast corner of Euclid Avenue and East 9th Street—replacing an earlier chapel on the site, a large Gothic structure that was built in 1874. The once-residential neighborhood had turned commercial, and most of United Methodist’s congregation had moved east, so the church sold the property for $500,000 and hired J. Milton Dyer to design a new church at Euclid Avenue and East 30th Street.

.

Banks desiredimpressive buildings to convey an impression of strength, stability, and permanence.

The Cleveland Trust rotunda fit that bill admirably. Ingenuity was required. The site is not symmetrical due to the acute angle of the intersection and hiding this from the casual visitor was a challenge.

Millet painted a series of 13 five-foot by 16-foot murals— “Pioneer and Discovery,” which chronicle America’s colonization, cultivation, and development. Millet’s works can also be found in the Metzenbaum Courthouse, where architect Arnold Brunner commissioned Millet to create a mural series, “Mail Delivery,” which 35 images on 23 canvas panels in the postmaster’s office.

He survived hard service in the Union Army to achieve fame as a war correspondent several years later. Starting as an avocation his skill as an artist lead to a career change. Although Millet was married to Elizabeth "Lily" Greely Merrill, and the couple had four children together, it was widely believed he was also in a relationship with journalist and U.S. Army officer Archibald Butt.

Several years after Millet worked on the rotunda, he joined Butt on a trip to Europe intended as a relaxing vacation. The fates dictated otherwise as both men found themselves returning on the maiden voyage of the Titanic. Neither man survived. While Butt disappeared, Millet’s body was recovered and released to his son, who brought it home for burial.

Ground was broken late in 1905 and the building required two years to complete. The projected cost was $ 600,000. This cost rose appreciably, most likely because the project took far longer than planned and ultimately cost $1million. The building was completed in late 1907.

After many years of daily service, the rotunda was closed for more than a year in the early 1970s for an extensive renovation.

Heinen’s grocery store opening in 2015 formerly the Cleveland Trust Company RotundaThis involved substantial modernization of the building’s infrastructure including installing modern air conditioning and upgrading other utilities.

Heinen’s grocery store opening in 2015 formerly the Cleveland Trust Company RotundaThis involved substantial modernization of the building’s infrastructure including installing modern air conditioning and upgrading other utilities.

A merger with Society National Bank in 1991 cost Cleveland Trust its identity. Yet another merger two years later between Society and Key Bank created a new bank called KeyCorp. All banking operations then became concentrated in Key Tower on Public Square.

Rendered superfluous, the rotunda was closed in December 1996 ending nearly a century of service to Cleveland’s banking community.

But then, in an unusual example of adaptive reuse, in February 2015 the venerable building has been repurposed as Heinen’s grocery store, today serving the needs of downtown residents.

About the Author: Tom Matowitz

Recently retired after a 37-year career teaching public speaking, Tom Matowitz has had a lifelong interest in local and regional history. Working as a freelance author for the past 20 years he has written a number of books and articles about Cleveland’s past. He has a particular interest in the area’s rich architectural history.