Rafael Guastavino, known for majestic vaulted ceilings in the West Side Market, Baldwin water plant

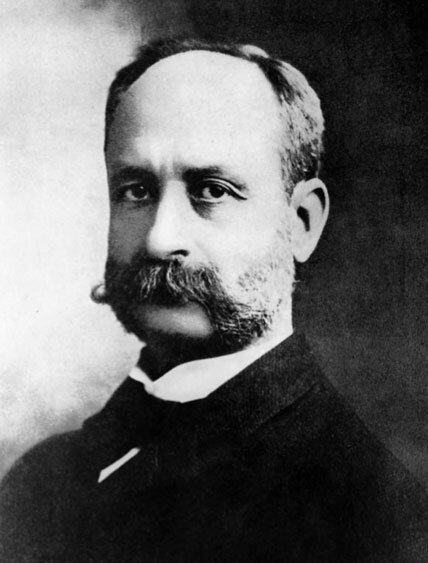

One of the more unusual figures in Cleveland’s architectural history is Rafael Guastavino.

Rafael GuastavinoBorn in Catalonia, Spain in 1842, he was from a large family of musicians. But Guastavino chose a different path, and in 1861 began an excellent technical education in Barcelona at the Escola Especial de Mestres d’Obres.

Rafael GuastavinoBorn in Catalonia, Spain in 1842, he was from a large family of musicians. But Guastavino chose a different path, and in 1861 began an excellent technical education in Barcelona at the Escola Especial de Mestres d’Obres.

The school provided excellent training for graduates seeking careers as master builders. Taught by renowned faculty made up of the leading architects of Catalonia, the course of study was arduous and took Guastavino 11 years to complete.

He aspired to certification as an architect, and took courses to further this goal, but never actually became an architect.

His life’s work was closely related to the field, since he invented a system of interlocking tiles that greatly facilitated the construction of vaulted ceilings. He improved upon a traditional Spanish system known as Catalan, or timbrel vault, which created economical, lightweight, and fireproof vaulted ceilings.

Traditional methods relied on elaborate wooden forms, called centering, and often used heavy stone blocks or brickwork and relied on substantial walls to provide support for finished ceilings.

Guastavino's process eliminated the need for centering, using interlocking ceramic tiles that were lighter and stronger than previous methods. Since centering wasn't required, and the plaster used to set the tiles cured quickly, construction could proceed at a rapid pace and saved money. His technique became very successful.

Well known in Spain by the early 1870s, Guastavino began to expand his influence by submitting designs to the 1876 Centennial Exhibition in Philadelphia. Five years later he made an abrupt decision to move to the United States. His personal life was turbulent, and it is suggested that he took this drastic step to place a failed marriage behind him.

Built in 1914, the Guastavino vaulted staircase in Baker Hall at Carnegie Mellon University is so complex that MIT students have not yet figured how to replicate it.The move led to great success as Guastavino established a firm based in New York City, R. Guastavino Co., and found commissions across the United States. The firm existed until 1962.

Built in 1914, the Guastavino vaulted staircase in Baker Hall at Carnegie Mellon University is so complex that MIT students have not yet figured how to replicate it.The move led to great success as Guastavino established a firm based in New York City, R. Guastavino Co., and found commissions across the United States. The firm existed until 1962.

A series of disastrous building fires across the country in the late 1800s and early 1900s—such as the Chicago fire of 1871, the Iroquois Theater fire in 1903, and the Triangle Shirtwaist fire in 1911—led to great concern about fireproof construction in the United States in this period. Guastavino’s methods were in the forefront of this movement, since they did not use flammable materials leading to structures far less vulnerable to fire.

His timing was excellent. There was great demand for Guastavino’s product and methods, and he found work across the United States. His Guastavino tile was patented in the United States in 1885. He adapted completely to his new life in this country—to such an extent that although he lived well into the 20th Century, he never returned to Spain, dying at his home in Black Mountain, North Carolina on February 2, 1908.

R. Guastavino Co. worked with architectural firms on more than 1,000 buildings around the United States, including more than 200 in New York—including Grand Central Station, the Cathedral of St. John the Divine, the Ellis Island immigrant station, and the Federal Reserve Bank.

R. Guastavino Co.’s work can be seen in more than 30 states and four foreign countries. The heaviest concentration is in the New England states, particularly New York, and

17 examples are found in Ohio, constructed between 1911 and 1932.

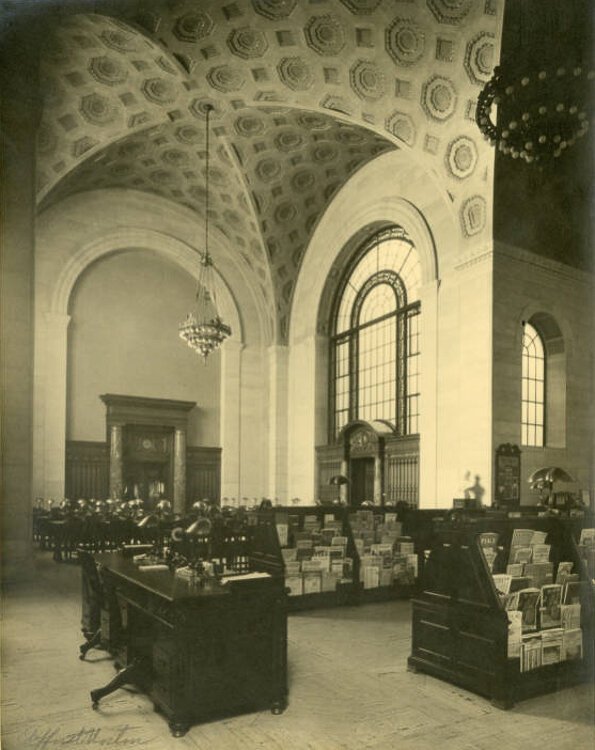

A dozen examples of his work survive today in the Cleveland area. The most notable is the Hubbell & Benes-designed West Side Market, where Clevelanders have done their grocery shopping beneath a Guastavino ceiling for 110 years.

Guastavino's vaulted ceilings are in the Baldwin Water Treatment Plant, a 1924 design by Herman Kregelius. Other examples figure in the design of the 1924 Walker & Weeks-designed Cleveland Public Library.

Visitors to Lake View Cemetery may see an example in the Hanna Family Mausoleum. A prominent illustration of Guastavino’s work may be seen in the Epworth-Euclid United Methodist Church in University Circle.

Hanna Mansion boasts a roofed structure extending from the entrance of a building over an adjacent driveway with a ceiling installed by R. Guastavino Co. in 1909.A rare instance of a McKim, Mead, and White structure in the Cleveland area, the Hanna Mansion on Lake Shore Boulevard in Bratenahl boasts a porte corchere (a roofed structure extending from the entrance of a building over an adjacent driveway to shelter those getting in or out of vehicles) with a ceiling installed by R. Guastavino Co. in 1909.

Hanna Mansion boasts a roofed structure extending from the entrance of a building over an adjacent driveway with a ceiling installed by R. Guastavino Co. in 1909.A rare instance of a McKim, Mead, and White structure in the Cleveland area, the Hanna Mansion on Lake Shore Boulevard in Bratenahl boasts a porte corchere (a roofed structure extending from the entrance of a building over an adjacent driveway to shelter those getting in or out of vehicles) with a ceiling installed by R. Guastavino Co. in 1909.

The high survival rate of the firm’s work across the United States is a testament to the imagination and quality of its design work and the skill of the artisans who executed it.

About the Author: Tom Matowitz

Recently retired after a 37-year career teaching public speaking, Tom Matowitz has had a lifelong interest in local and regional history. Working as a freelance author for the past 20 years he has written a number of books and articles about Cleveland’s past. He has a particular interest in the area’s rich architectural history.