The Soldiers' and Sailors' Monument: Honoring Cuyahoga County’s Civil War veterans

Thirty years after the Civil War ended, the young veterans of the late 1860s were middle aged men with time to reflect on the war experiences that defined their lives between 1861 and 1865.

Their service was far flung and included every theater and branch of service. Young men from Cleveland fought at Antietam and Gettysburg and served aboard naval vessels enforcing the blockade. They marched to the sea with William Tecumseh Sherman. They rode horseback in elite cavalry units and fired many rounds of ammunition from field artillery pieces on dozens of well-known battle fields.

By the early 1890s old soldiers wanted to remember the sacrifices they made and honor the memory of fallen comrades. This was a national trend as Civil War monuments began to appear on court house squares across the country.

Interest in this concept began early with the creation of a pyramid of stone on the battlefield of Stones River in Tennessee, shortly after the battle was fought at the end of 1862. This marker—the Hazen Brigade Monument—is said to be America’s earliest Civil War monument and it survives to this day.

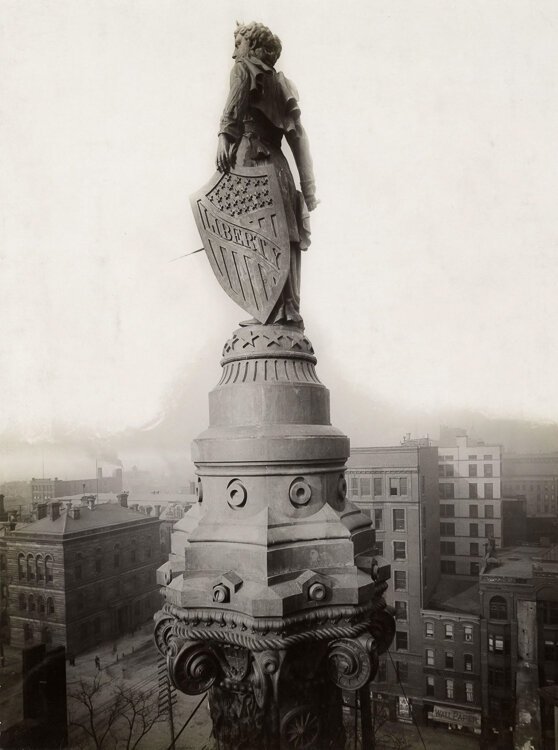

Here in Cleveland a commission was formed in order to determine the city’s best response to this perceived need. The need was fulfilled by Soldiers’ and Sailors’ Monument in Public Square.

Levi T. ScofieldOne of the most important figures to serve on this project was Levi Scofield. One of the city’s top architects at the time of his selection, 30 years earlier he was part of the throng of young Clevelanders who rushed to the sound of the guns.

Levi T. ScofieldOne of the most important figures to serve on this project was Levi Scofield. One of the city’s top architects at the time of his selection, 30 years earlier he was part of the throng of young Clevelanders who rushed to the sound of the guns.

A generation later, Scofield was a community leader with strong ties to Union veteran’s organizations. He was involved with the proposed Public Square monument from its earliest planning stages.

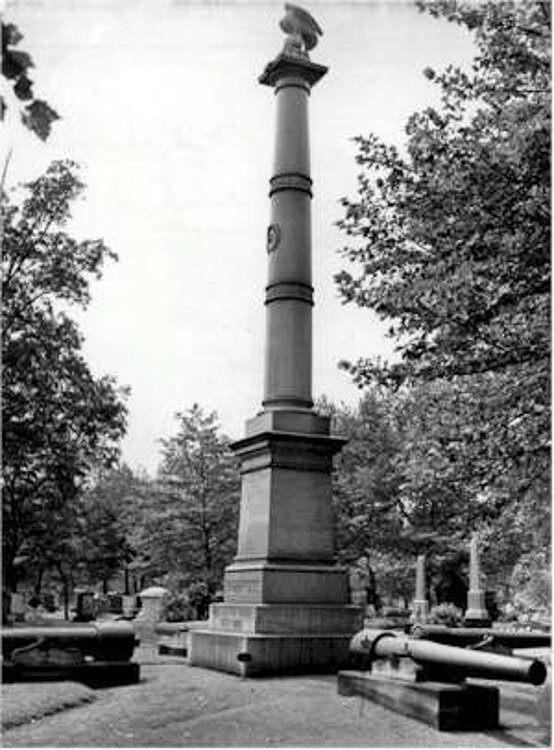

Clevelanders staunchly supported the Union war effort, and one of the first Civil War monuments in the country was a memorial placed in Cleveland’s Woodland Cemetery to honor men who lost their lives serving in the 23rd Ohio Volunteer Infantry. This monument was completed in July 1865, just months after the war was over. Two future presidents were present for the dedication, Rutherford B. Hayes and William McKinley. Both served in the regiment during the war.

In 1868, the Federal government purchased two parcels of land in the cemetery to bury Civil War dead. Today, these parcels are knowns as Woodland Cemetery Soldiers’ Lot and host the remains of 48 Union soldiers.

Woodland Cemetery has three monuments dedicated to the service and sacrifice of Union men in both the 23rd and 7th Ohio Volunteer Infantry Regiments, and the Grand Army of the Republic (G.A.R.).

Given the iconic status of the Soldier’s and Sailor’s Monument it is hard to believe that there was initially resistance to placing it on Public Square.

Opponents argued that it would disrupt traffic patterns and reduce property values. In the proposed monument’s favor was the vast influence of the G.A.R. This Union veterans organization held great political power in the early 1890s. Local chapters strongly supported the monument which proposed to honor everyone from Cuyahoga County who served.

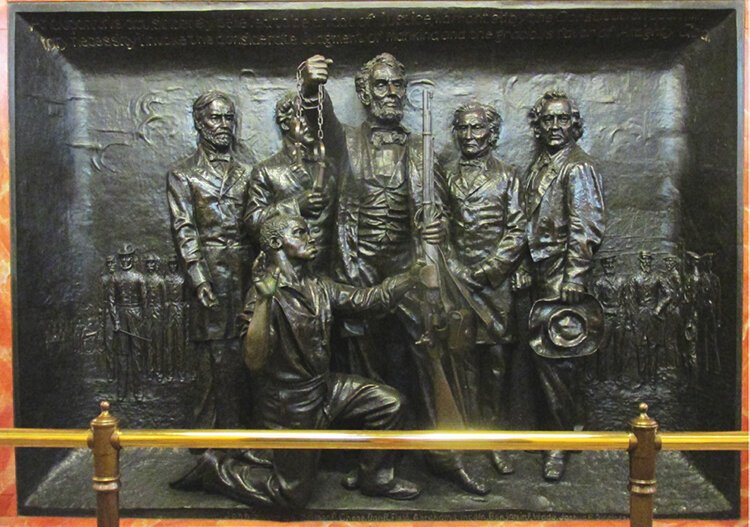

Scofield was selected to design the monument. His work included a number of bronze statues illustrating various scenes of the war. These sculptures are notable for their inclusion of Black combatants—long before their service was generally recognized.

Scofield’s wife, Elizabeth Clark Wright Scofield, played a critical role in the monument’s design, poring over decades-old written records to ensure that the names of 9,000 veterans inscribed within the monument were recorded accurately.

Scofield’s wife, Elizabeth Clark Wright Scofield, played a critical role in the monument’s design, poring over decades-old written records to ensure that the names of 9,000 veterans inscribed within the monument were recorded accurately.

On July 4, 1894, the monument was dedicated with great ceremony. Although the day was rainy thousands attended. Those present included William McKinley, who, 29 years earlier, stood in a crowd at the dedication of the 23rd Ohio Volunteer Infantry Monument at Woodland. In 1894 McKinley presided over the dedication of the Soldiers and Sailors Monument as president of the United States.

He proved to be the last Civil War veteran to hold the Presidential office. McKinley’s military service was important to him. In middle age he was asked what title he preferred: congressman or governor? He replied, “Call me major. I earned that. I’m not so sure of the rest.”

The Soldiers’ and Sailors’ Monument figured in ceremonies relating to the Civil War for years. In 1901 a G.A.R. encampment brought almost 300,000 visitors to Cleveland, and 46 years later the 81st annual G.A.R. encampment was held in Cleveland.

Time had inevitably done its work. In 1947 the once mighty organization claimed only 66 members. The final encampment in 1949 included just six Union veterans from a total of sixteen survivors.

Almost 130 years after it was built, the Civil War veterans the Soldiers’ and Sailors’ Monument was erected to honor are long gone, finally compelled to surrender—to the passage of time.

About the Author: Tom Matowitz

Recently retired after a 37-year career teaching public speaking, Tom Matowitz has had a lifelong interest in local and regional history. Working as a freelance author for the past 20 years he has written a number of books and articles about Cleveland’s past. He has a particular interest in the area’s rich architectural history.