St. Agnes Church: Weathered the Depression, racial tensions in Hough before its demise

For nearly 50 years motorists on Euclid Avenue have questioned the presence of a bell tower standing alone at the intersection of Euclid and East 81st Street.

Located on a large grassy plot, the bell tower’s origins have become obscure.

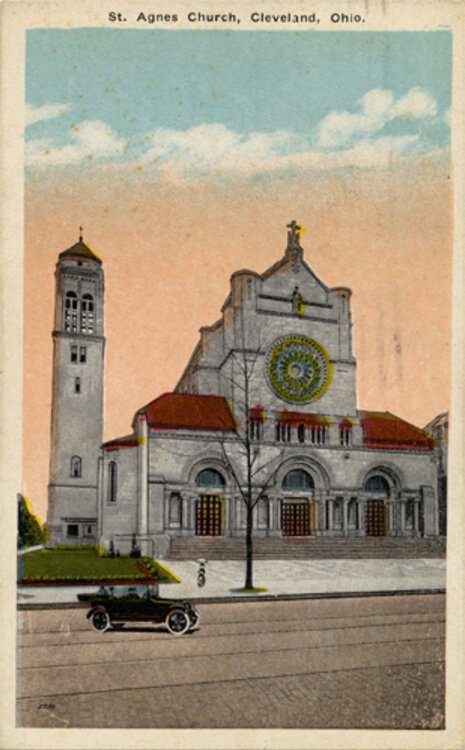

St. Agnes Church postcardTo learn the history of the sole remaining element of the 1916 St. Agnes Church—and architect John T. Comès’ only Cleveland design—it is necessary to look back more than 100 years.

St. Agnes Church postcardTo learn the history of the sole remaining element of the 1916 St. Agnes Church—and architect John T. Comès’ only Cleveland design—it is necessary to look back more than 100 years.

In 1888, a group of catholic women in the Hough neighborhood—which was predominantly white until the 1950s—lobbied Cleveland bishop Richard Gilmour to establish an east side Catholic church where services would be conducted in English.

Existing Catholic churches in Cleveland at the time served ethnic congregations with services often conducted in the congregations’ native languages.

After Gilmour’s death, the women continued to plead their case to bishop Ignatius F. Hortsman and were successful.

The cornerstone for the new St. Agnes Church was placed in March 1914.

Its designer was John T. Comès, a Pittsburgh architect who specialized in the design of grand Catholic Churches. He was born in Luxembourg in 1873 and brought to the United States as a child. He was one of five siblings, only two of whom survived to adulthood.

Comès grew up in St. Paul, Minnesota and attended parochial schools there. Comès began working in Pittsburgh in 1896 and established his own firm by 1902. He became widely known for his skill as a designer of grand churches and cathedrals. Bishops across the United States consulted with Comès, who was a highly regarded member of the American Institute of Architects (AIA).

Comès became seriously ill late in 1921 and died of cancer the following April at the early age of 49.

St. Agnes was the only example of his work in Cleveland. Under construction for more than two years, the church was dedicated by Bishop John P. Farrelly on June 18, 1916.

The new building was notable as the last grand church constructed on Euclid Avenue in what had to be considered the very end of the era of Millionaire’s Row.

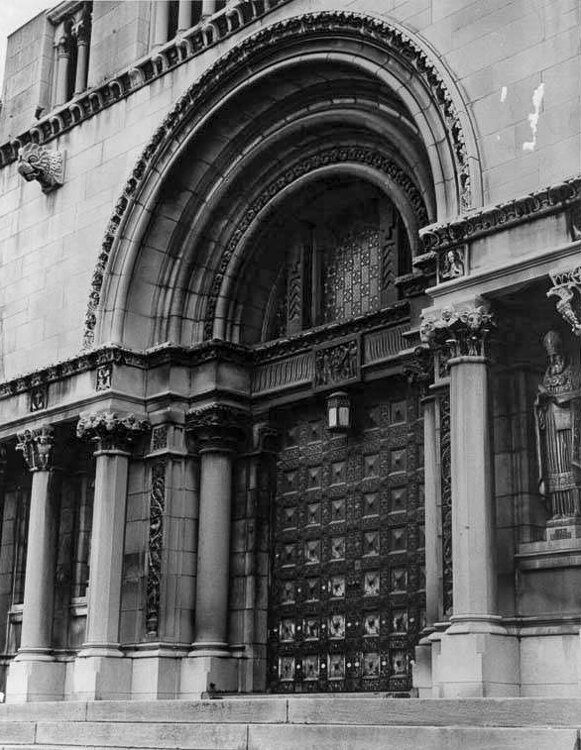

An interior view of the altar at St. Agnes Catholic Church. The photograph was taken during funeral services for Auxiliary Bishop John R. Hagan in 1946.The new church presented a magnificent French Romanesque design executed in Bedford stone and was notable for three deeply recessed doors surmounted by a large rose window. The interior was embellished by a large mural, “Christ in Majesty,” painted by noted artist Felix Lieftuchter in the church nave.

An interior view of the altar at St. Agnes Catholic Church. The photograph was taken during funeral services for Auxiliary Bishop John R. Hagan in 1946.The new church presented a magnificent French Romanesque design executed in Bedford stone and was notable for three deeply recessed doors surmounted by a large rose window. The interior was embellished by a large mural, “Christ in Majesty,” painted by noted artist Felix Lieftuchter in the church nave.

Born in Cincinnati in 1882, Lieftuchter was formally trained as an artist in Germany and had several notable collaborations with John Comès.

The parish initially prospered, but demographic changes in the neighborhood would ultimately spell doom for the church. A series of strong leaders delayed this process for as long as they could. But, the church’s devoted founding pastor, Monsignor Gilbert P. Jennings died in April 1941, ushering in a difficult era for St. Agnes.

In January 1949, the church’s fortunes changed with the assignment of Father Floyd Begin as pastor. He recognized the changes in the neighborhood and embraced them—encouraging Black residents to join the parish and promoted inclusion and imaginative approaches to the social problems and racial tensions that beset the area.

Father Begin’s efforts weren’t enough. In the 1960s Begin was reassigned and the church began to falter again—confronted by almost insurmountable financial difficulties. As the church’s fate was being decided, a Diocesan official was quoted as saying that the Catholic Diocese was not in the business of preservation.

In October 1975 Plain Dealer religion writer Darrell Holland wrote an article titled “Buildings go, People first, Catholic spokesman says.” The story covered the diocese’s plans to demolish St. Agnes and two other Cleveland churches. The Diocesan secretary for parish life and development, Rev Dr. John L. Fiala, responded to the suggestion that the church was “deserting the inner city because it was mostly Black.”

Saying that the church was not in the “business of restoration of old buildings, but exists to deal with the needs of the people.” He went on to say:

“One Black member said to me when we were discussing tearing down the building, ‘This is not a Black church, It is a European church…It’s beautiful but Blacks would never feel at home here and it would not meet the needs of the Black neighborhood.”

Demolition of St. Agnes Church in 1976We will never know.

Demolition of St. Agnes Church in 1976We will never know.

The church was demolished on Nov. 24, 1975, taking its place in a long line of once magnificent Cleveland churches that succumbed to changing times, interstate highway construction, and plain old indifference.

Built for the ages, in the end St. Agnes lasted for just two generations.

The silent bell tower alone remains, a reminder of past greatness, and the loss of what was arguably one of Cleveland’s most significant 20th Century buildings.

About the Author: Tom Matowitz

Recently retired after a 37-year career teaching public speaking, Tom Matowitz has had a lifelong interest in local and regional history. Working as a freelance author for the past 20 years he has written a number of books and articles about Cleveland’s past. He has a particular interest in the area’s rich architectural history.