The Van Sweringen brothers: Developers of the Terminal Tower

In 1866 a new railroad depot was built on Cleveland’s lakefront. Designed by noted railroad executive Amasa Stone, it was a large structure—603 feet by180 feet—making it the largest building under one roof in the United States as well as the largest railroad depot. It held these titles until Grand Central Station was constructed in New York City.

By the early 20th Century, the Cleveland Union Depot had seen better days. Its location was isolated and its appearance dingy.

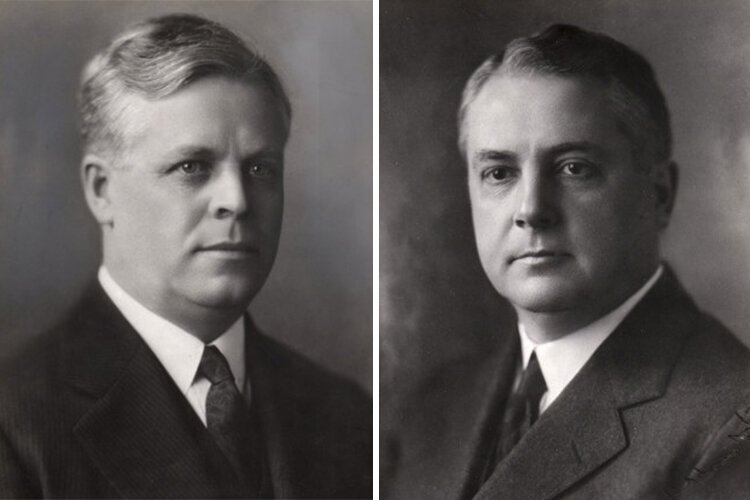

Mantis and Oris Van Sweringen 1935Noted real estate developers and brothers O. P. (Oris Paxton) and M. J. (Mantis James) Van Sweringen—foremost known for their development of Shaker Heights—addressed this situation with a plan for a new depot to be located on Public Square.

Mantis and Oris Van Sweringen 1935Noted real estate developers and brothers O. P. (Oris Paxton) and M. J. (Mantis James) Van Sweringen—foremost known for their development of Shaker Heights—addressed this situation with a plan for a new depot to be located on Public Square.

It was to be more than simply a depot—the new Cleveland Union Terminal, what is today known as the Terminal Tower, would be a complex involving a hotel and retail spaces.

Construction of the Terminal Tower transformed Public Square. Instead of the rundown 1860s structure on the lakefront, visitors were greeted by a state-of-the art facility that provided high end retail, top quality dining, a modern hotel, and a range of business services, all within walking distance.

Previously, the southwest quadrant of Public Square had no unifying feature other than an atmosphere of neglect and obsolescence.

The new structure identified Cleveland as a world class city.

But the plan also involved the destruction of a familiar Cleveland neighborhood and change that would be irreversible. The footprint of the new structure required the destruction of 2,000 buildings, as well as the vacating of a large grid of streets that would simply cease to exist.

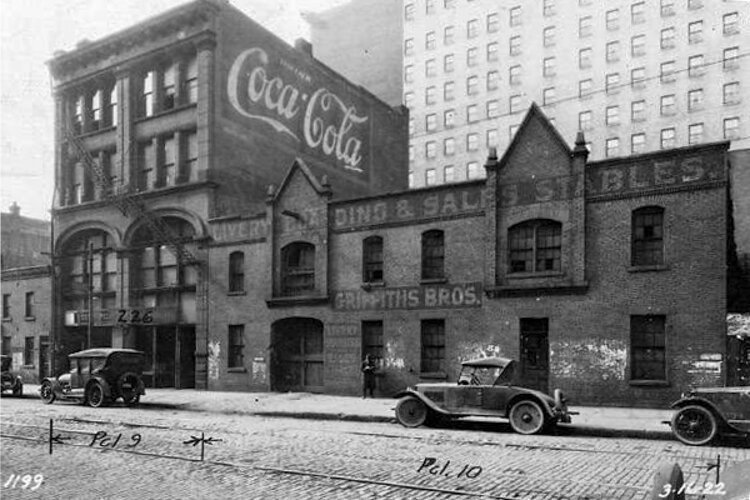

Second Central Station and Patrol Station #1 early 1920'sAmong the buildings slated for destruction was Cleveland Police Headquarters in the old Champlain Street Police station at the corner of West 6th and Champlain Streets. This large complex housed the city jail and courtrooms in addition to police headquarters. An adjoining building housed a stable for horses that provided the department's motive power. Destruction of these buildings ended a police presence in the neighborhood that began in the Civil War era. Nearby stood recently-completed office building the housed the headquarters of the local telephone company, as well as a Cleveland Fire station. These and all the others were erased as completely as if they had never existed.

Second Central Station and Patrol Station #1 early 1920'sAmong the buildings slated for destruction was Cleveland Police Headquarters in the old Champlain Street Police station at the corner of West 6th and Champlain Streets. This large complex housed the city jail and courtrooms in addition to police headquarters. An adjoining building housed a stable for horses that provided the department's motive power. Destruction of these buildings ended a police presence in the neighborhood that began in the Civil War era. Nearby stood recently-completed office building the housed the headquarters of the local telephone company, as well as a Cleveland Fire station. These and all the others were erased as completely as if they had never existed.

This project didn’t come cheap. It is estimated that this venture cost $170 million—a steep price in the 1920s.

Chicago-based architecture firm Graham, Anderson, Probst, and White (the successor of Burnham & Root, designers of the Western Reserve and Cuyahoga Buildings) was chosen to design the Terminal Tower.

The proposed new building would completely alter the character of Public Square. The southwest corner of the square was lined by undistinguished low rise commercial buildings adorned by a thicket of advertising signage.

All of this was swept away and replaced by a skyscraper, with a design that was said to have been inspired by celebrated New York architects McKim, Mead, and White (who designed noted structures such as the former Pennsylvania Station in New York City, the campus of Columbia University, the Brooklyn Museum, and the Boston Public Library).

Construction on the Cleveland Union Terminal began in 1926 after several years of advance planning and the acquisition of property. It was necessary to sink caissons 250 feet to reach bedrock. Construction took four years. The new building was anchored on its west side by the 1918 Hotel Cleveland, an earlier Van Swearingen project built with the eventual tower in mind.

As the tower rose so did the Van Sweringen fortunes. Their business empire was said to be worth $300 billion by 1929 but, ominously, this was largely based on leveraging borrowed funds.

Terminal Tower lobbyThe Cleveland Union Terminal opened on schedule in 1930, but the Van Sweringens’ days were numbered. Both men died by the end of 1936, their paper fortune largely gone, thanks to the Great Depression.

Terminal Tower lobbyThe Cleveland Union Terminal opened on schedule in 1930, but the Van Sweringens’ days were numbered. Both men died by the end of 1936, their paper fortune largely gone, thanks to the Great Depression.

In Cleveland, the Terminal Tower remains the Van Sweringens’ best-known monument, although skyscraper is perhaps rivaled by their development of Shaker Heights—their first great success as a benchmark as one of the country’s first planned communities, as well as a showcase for some of the finest residential architecture to be found anywhere in the country.

For years, the Terminal Tower was the tallest building between New York City and Chicago. Recent years have seen it overshadowed by taller buildings on Public Square, but the tower remains a symbol of Cleveland to this day.

For 85 years the Van Sweringens have lain side by side in Lake View Cemetery beneath a plain tombstone inscribed “Brothers.”

About the Author: Tom Matowitz

Recently retired after a 37-year career teaching public speaking, Tom Matowitz has had a lifelong interest in local and regional history. Working as a freelance author for the past 20 years he has written a number of books and articles about Cleveland’s past. He has a particular interest in the area’s rich architectural history.