A tale of two steamers: The tragic stories of The Western Reserve and the W.H. Gilcher

The Great Lakes became a highway of commerce in the late 19th Century. The ships that made this possible had changed drastically in design features, compared with the wooden schooners that first carried cargo in the region.

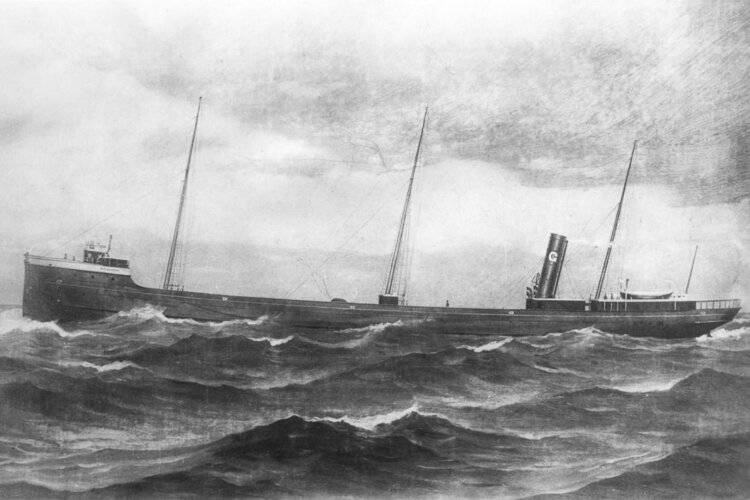

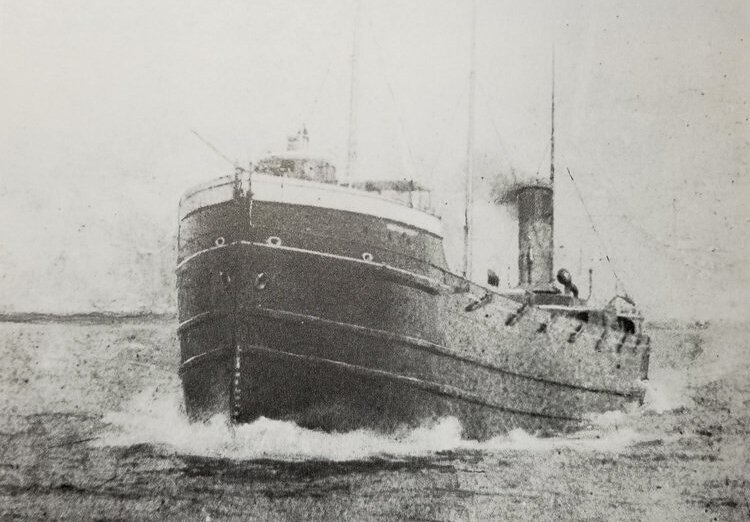

The steamer R.J. Hackett, built in Cleveland in 1869The steamer R.J. Hackett, built in Cleveland in 1869, pioneered the configuration of a pilothouse forward, a long unobstructed spar deck with hatches leading to a cargo hold, and the engine room and the galley aft.

The steamer R.J. Hackett, built in Cleveland in 1869The steamer R.J. Hackett, built in Cleveland in 1869, pioneered the configuration of a pilothouse forward, a long unobstructed spar deck with hatches leading to a cargo hold, and the engine room and the galley aft.

Despite these design improvements the vessel was still constructed of wood.

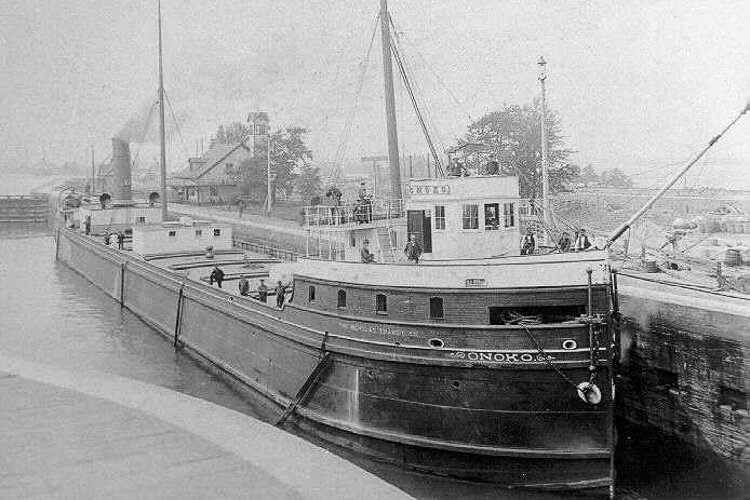

The next big innovation was the steamer Onoko—launched in 1882. It was the first Great Lakes freighter built of iron.

This ship was rendered obsolete in 1890 when the Globe Shipbuilding Company in Cleveland and its counterpart, Cleveland Shipbuilding (the two later joined in a merger that formed American Ship Building Company), built two new freighters made of steel.

Three hundred feet in length, these ships were large in their day, and the use of steel in their construction was considered very advanced.

The ships’ names were Western Reserve and W.H. Gilcher. The pride and excitement that attended their launch and entry into service quickly turned to grief and bewilderment—as both ships proceeded to sink with heavy loss of life when they were just slightly more than a year old.

The Western Reserve was lost first on the night of Aug. 30, 1892. Traveling without cargo, the ship was enroute to Two Harbors, Minnesota.

The circumstances were particularly tragic. In addition to the vessel’s crew, those on board included owner Captain Peter G. Minch, his wife, and two children traveling as vacationers. Minch’s sister-in-law and his niece were also present.

The only clue to the ship’s fate was the survival of 24-year-old wheelsman Harry W. Stewart, the only person to escape losing his life with the ship.

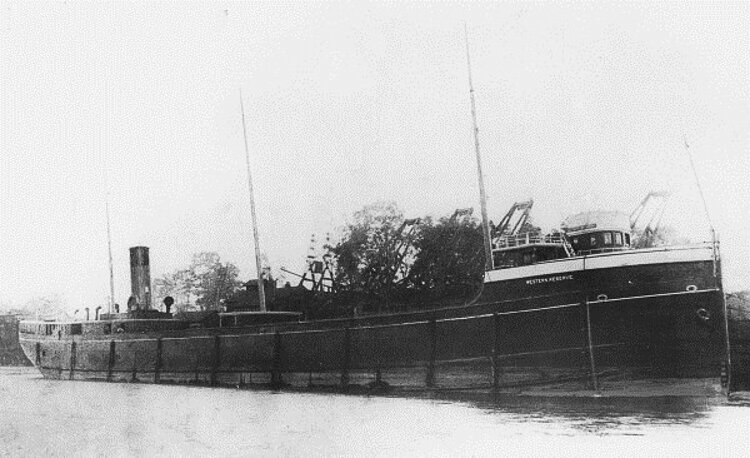

The Western Reserve was lost enroute to Two Harbors, Minnesota on the night of Aug. 30, 1892He reported that the Western Reserve broke in half without warning around 9 p.m. Two lifeboats were launched. One lifeboat capsized quickly, and two survivors were recovered by the second boat.

The Western Reserve was lost enroute to Two Harbors, Minnesota on the night of Aug. 30, 1892He reported that the Western Reserve broke in half without warning around 9 p.m. Two lifeboats were launched. One lifeboat capsized quickly, and two survivors were recovered by the second boat.

At 7 a.m. the following morning the lifeboat carrying Stewart and the others capsized a mile offshore—drowning everyone but Stewart, who made it to land exhausted after a struggle lasting for two hours.

Stewart then willed himself to walk 12 miles to the nearest lifesaving station, Deer Park on Michigan’s Upper Peninsula. He recovered and returned to the Great Lakes, rising to be a captain before dying at age 70 in 1938.

Valued at $ 200,000 at the time of her sinking, the Western Reserve was the largest insurance loss involving a Great Lakes freighter in the 19th Century.

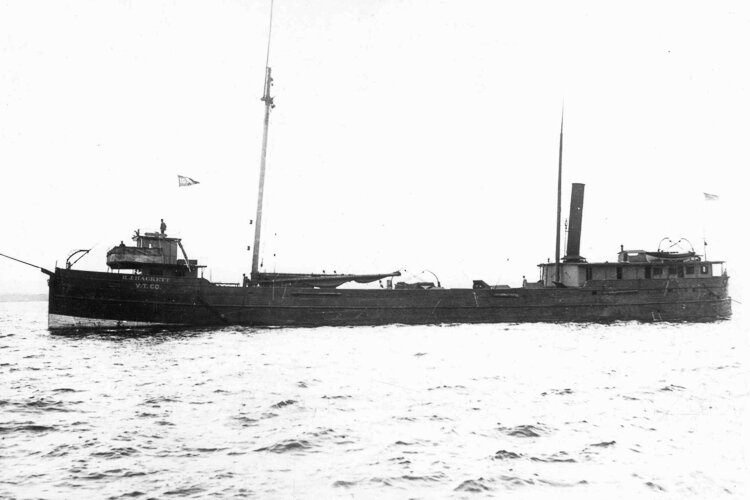

The W. H. Gilcher followed the Western Reserve to disaster less than 60 days later. Built by the Cleveland Shipbuilding Company, the ship was carrying a crew of 18 and loaded with a cargo of coal bound for Milwaukee, when it sailed into a moderate Lake Michigan gale on Oct. 28, 1892, and simply disappeared. This time there would be no survivors to recount what happened.

Despite modern search methods used for years, neither wreck has ever been located.

An investigation indicated that the two ships broke in half due to a flaw in the steel plates with which they were constructed, rendering their hulls rigid and inflexible.

Nearly 50 lives were lost when these two ships sank, and the story has a particularly sad postscript.

Discovered among planks and cordage that washed ashore after the sinking of the Western Reserve, was the ship’s green starboard running light.

The eldest son of the Minch family otherwise lost in the sinking was Phillip J. Minch—who did not travel with his parents and younger siblings because he was recovering from an illness.

The running light was given to him.

In later life this running light was wired for electricity and displayed in a window in his home in Mentor.

The house was named Starboard Light, and Phillip Minch kept the light burning in memory of his lost family every day for as long as he lived.

Harry AndersonThis article is respectfully dedicated to the memory of Harry Axel Anderson (born October 5, 1909, and died May 22, 2013 at age 103). A 42-year employee of Cleveland Cliffs, he was the fleet’s senior captain upon retirement in 1974. No finer gentleman ever graced the pilothouse of a Great Lakes freighter and no one else did more to encourage my interest in the history of Great Lakes shipping.

Harry AndersonThis article is respectfully dedicated to the memory of Harry Axel Anderson (born October 5, 1909, and died May 22, 2013 at age 103). A 42-year employee of Cleveland Cliffs, he was the fleet’s senior captain upon retirement in 1974. No finer gentleman ever graced the pilothouse of a Great Lakes freighter and no one else did more to encourage my interest in the history of Great Lakes shipping.

Thank you, Harry.

About the Author: Tom Matowitz

Recently retired after a 37-year career teaching public speaking, Tom Matowitz has had a lifelong interest in local and regional history. Working as a freelance author for the past 20 years he has written a number of books and articles about Cleveland’s past. He has a particular interest in the area’s rich architectural history.