The Union Club: Celebrating 150 years of elite social membership

For more than a century Cleveland has hosted important social clubs as venues for prominent citizens to gather and socialize. Some, like the Rowfant Club on Prospect Avenue, promoted intellectual pursuits like the study of books. Others, like the Hermit Club, off Playhouse Square on Dodge Court, were more social in nature, and devoted to theater and the arts.

One of the oldest such clubs is the Union Club, 1211 Euclid Ave., incorporated on September 25, 1872—next month celebrating 150 years of continuous operation.

he Union Club of Cleveland located on Euclid Avenue as it was in 1906The founding members included a cross section of Cleveland’s most influential citizens. Among the founding members were notable Cleveland figures Samuel Mather, Henry B. Payne, and William J. Boardman.

he Union Club of Cleveland located on Euclid Avenue as it was in 1906The founding members included a cross section of Cleveland’s most influential citizens. Among the founding members were notable Cleveland figures Samuel Mather, Henry B. Payne, and William J. Boardman.

In a distinction likely to remain unique, over the years the club’s membership came to include five U.S. presidents: Ulysses S. Grant, Rutherford B. Hayes, James A. Garfield, William McKinley, and William Howard Taft.

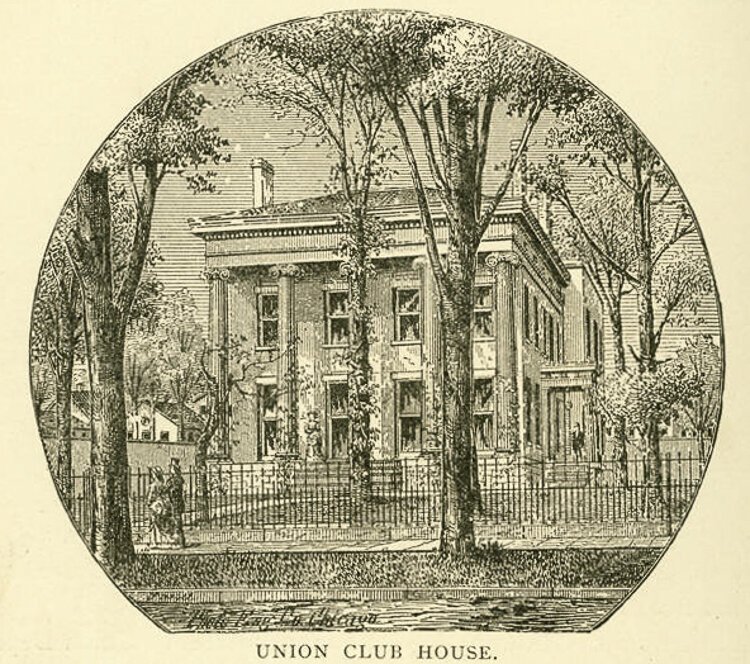

In 1872 the club purchased the former home of George B. Senter, located near the intersection of what is now East 6th Street and Euclid Avenue. Built in 1842 for prominent banker Truman Handy and designed by Jonathon Goldsmith, the Union Club paid $ 60,000 to make this two-story brick structure its first home. Senter, had died two years earlier, in 1870, after a notable career in politics and the military during the Civil War. He was responsible for logistics of several training camps and served as Cleveland’s mayor during the war.

An ardent Unionist throughout the war, it fell to Senter to proclaim a day of mourning on the day of Lincoln’s death, April 15, 1865.

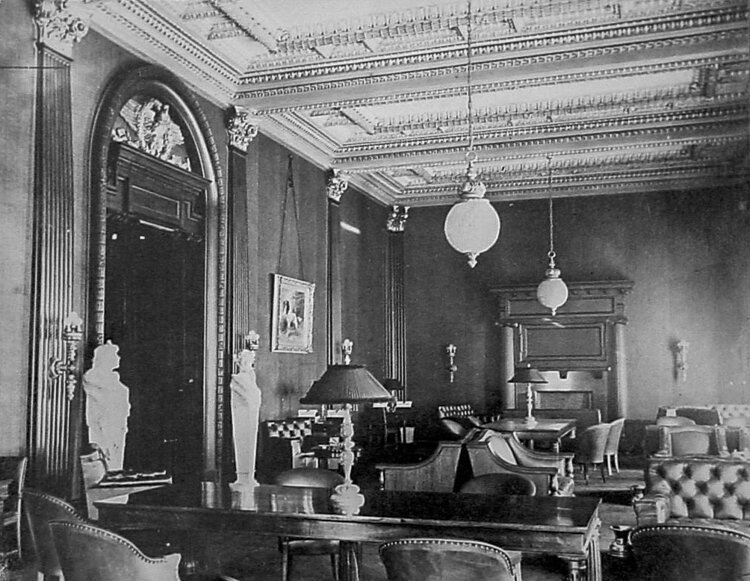

Ten years after the Union Club established its headquarters on Euclid Avenue, the facility provided a dining room and lounge for ladies but continued to deny them membership, a sexist policy later to be soundly rejected.

Beginning with a membership of 81 men, by the turn of the 20th Century the club’s roster included more than 500 men. On June 25, 1901, the Union Club was incorporated, becoming the Union Club Co.

The Club was badly needed a new clubhouse and the move to new quarters wasn’t very far—with the members purchasing what was once the Castle family home at East 12th Street and Euclid Avenue.

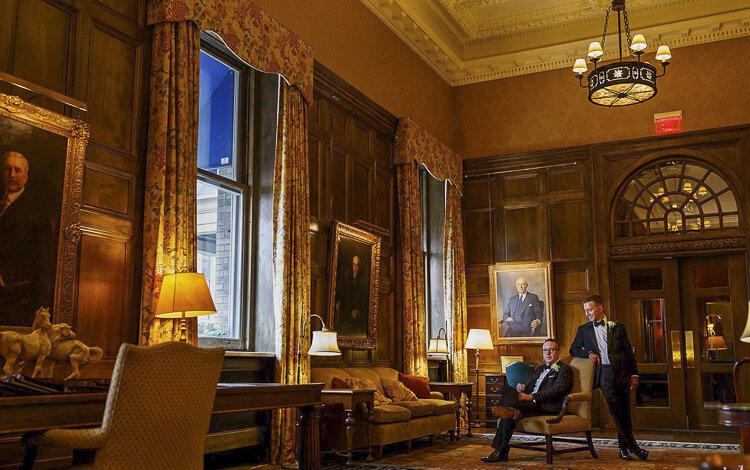

The new clubhouse was designed by Charles Schweinfurth, who was at the time at the height of his reputation as a Cleveland architect. He had come to the city in the early 1880s to design grand houses on Euclid Avenue. Originally, the club solicited a design from renowned New York architecture firm McKim, Mead & White. The firm’s plan was rejected in favor of the Schweinfurth plan—thus denying Cleveland a building designed by Stanford White.

Built with Amherst sandstone in an Italian Renaissance style, the new structure was ready for use by the end of 1905, dedicated with a ball in the clubhouse on Dec. 6. The membership by then had grown to almost 1,000—still entirely male.

For most of the 20th Century, women were relegated to second class status, given a side door to enter, and consigned to a separate dining room. Some argue convincingly that the side entrance offered privacy and freedom from traffic, noise, and confusion on Euclid Avenue sidewalks.

The ladies dining room was said to provide a congenial environment, free of cigars and discussion of business matters, which may have held little interest to the women dining there. In any case, this reflected different times and very different standards.

The ladies dining room was said to provide a congenial environment, free of cigars and discussion of business matters, which may have held little interest to the women dining there. In any case, this reflected different times and very different standards.

The 1983 appointment of Karen Horn as director of the Federal Reserve Bank of Cleveland rendered the Union Club’s archaic policy untenable. She was the first woman to be accorded full privileges, and literally opened doors for other women as they could now enter the clubhouse through the front door for the first time in the club’s 111-year history.

Having undergone a facelift in the past 20 years to remove a century of industrial pollution, the club’s exterior today has the warm glow of sandstone and an appearance that the attendees of the Union Club’s inaugural ball would quickly recognize.

Spanning three centuries, the club thrives today—an unmistakable landmark dating back to the days when Euclid Avenue was renowned as grandest street in Cleveland.

About the Author: Tom Matowitz

Recently retired after a 37-year career teaching public speaking, Tom Matowitz has had a lifelong interest in local and regional history. Working as a freelance author for the past 20 years he has written a number of books and articles about Cleveland’s past. He has a particular interest in the area’s rich architectural history.