Superior Viaduct: Cleveland's first high-level bridge

In Cleveland’s earliest days a problem arose—namely, how to get vehicle traffic across the Cuyahoga River in a quickly-developing city.

Although the traffic was sparse, on both the river and on the roads compared to today, it had to be accommodated. Teams of horses pulling wagons faced the challenge of climbing the grades leading to Cleveland and Ohio City from the river’s edge. The solution was a tall bridge with a structure high enough to handle this traffic without the obstacle of steep approaches.

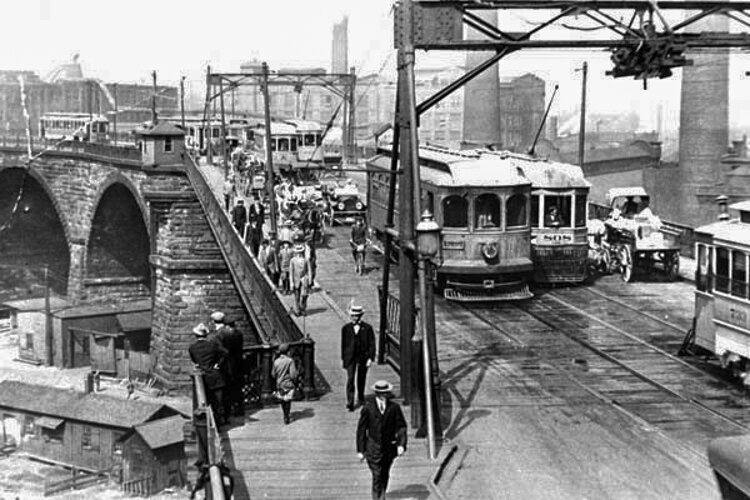

Streetcars, pedestrians, and private automobiles cross the Superior Viaduct, circa 1910sBy the 1870s the traffic issue had become acute. The answer was the Superior Viaduct—the city’s first high level bridge. Previously, the low-level bridges that required navigating the steep banks of the Cuyahoga and long waits for river traffic to pass.

Streetcars, pedestrians, and private automobiles cross the Superior Viaduct, circa 1910sBy the 1870s the traffic issue had become acute. The answer was the Superior Viaduct—the city’s first high level bridge. Previously, the low-level bridges that required navigating the steep banks of the Cuyahoga and long waits for river traffic to pass.

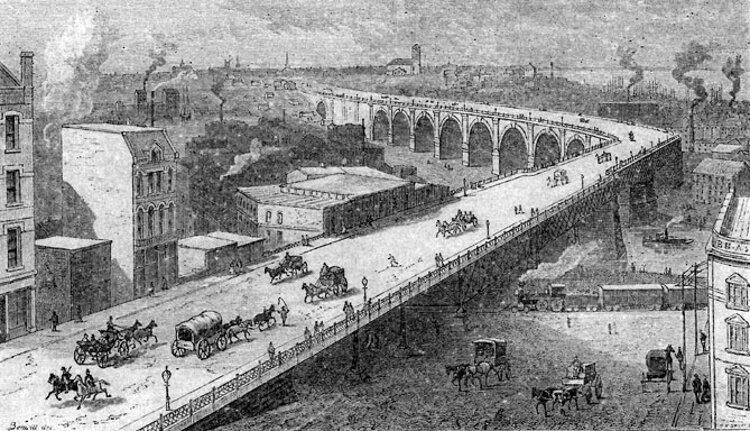

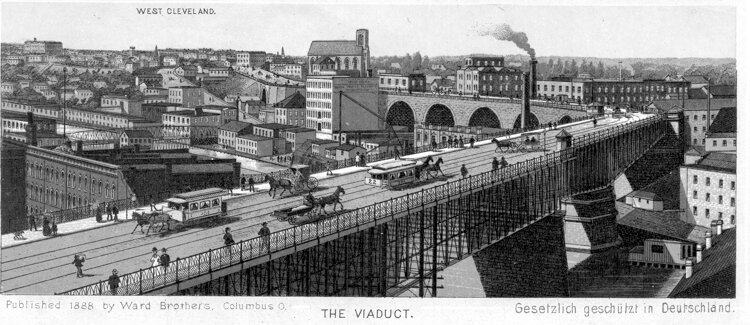

The term viaduct refers to a particular type of bridge—a structure incorporating a series of arches that typically carry a road or railroad across a valley. This sort of design extends back into antiquity.

Opened to traffic on December 27, 1878, overwrought newspaper reporting predicted that the bridge would last for 1,000 years. Described as an engineering marvel, the $2.17 million bridge design (the equivalent to more than $50 million today) contained an inherent flaw that would limit its useful life to roughly 40 years.

The problem was the river. The western approach involved 10 massive arches made from Berea sandstone. Carrying traffic to the east bank required a 322-foot-long swing section in the center because as tall as the bridge was, it could not provide clearance to all river vessel traffic without this pivoting section.

Passing cargo ships had priority, and each ship required five-minute interruptions of traffic on the bridge’s roadway—causing increasing ire of downtown commuters. This happened as many as 300 times per month and the 1,000-year bridge was used for the last time in 1922.

None of this was foreseen on the day the bridge opened. It took eight years of effort to reach that day, and a project so involved that it could be seen as the 19th Century’s answer to the Terminal Tower construction effort.

Planning for the bridge began in 1870 and was attended with much controversy. There were disputes about cost, routing, the question of tolls, and the economic impact it would have on both sides of the river.

After lengthy discussion actual construction of the bridge began in March of 1875 with driving 80-foot lines of 20-foot high wooden piles into the ground. By late May, the process of building the masonry arches began. The 10 stone arches amounted to a total length of 1,382 feet. Two million cubic feet of sandstone quarried in Berea was required to complete this segment of the finished bridge. Beyond the swing section, the east end of the bridge was composed of a 900-foot steel structure.

The bridge opened with great fanfare, celebrations, and testimonial dinners. A very welcome addition to the cityscape, as the years went by the swing span became increasingly problematic. The frequent cycling of the bridge to allow ships to pass became intolerable.

The idea of a new purpose for the remaining structure of the bridge has been raised several times. It has been suggested that shops and restaurants might be built to encourage visitors to linger creating a sort of Cleveland Ponte Vecchio.The viaduct was finally rendered obsolete by construction of the Detroit Superior high-level Bridge, which was completed in 1917. Somehow, the old Superior Viaduct swing span remained in use until 1922 when 150 pounds of dynamite brought it down.

The idea of a new purpose for the remaining structure of the bridge has been raised several times. It has been suggested that shops and restaurants might be built to encourage visitors to linger creating a sort of Cleveland Ponte Vecchio.The viaduct was finally rendered obsolete by construction of the Detroit Superior high-level Bridge, which was completed in 1917. Somehow, the old Superior Viaduct swing span remained in use until 1922 when 150 pounds of dynamite brought it down.

Seventeen years later in 1939, the three easternmost arches were destroyed with great difficulty in the course of a project to widen the Cuyahoga River.

Resembling something built by the Mayans the surviving arches remain in place providing an excellent vantage point for pedestrians seeking memorable views of Cleveland’s Flats. They are currently the subject of a study seeking a way to repurpose them for use in their third century.

The idea of a new purpose for the remaining structure of the bridge has been raised several times. This 1870s construction project was so well built that it has proven almost impossible to remove. It has been suggested that shops and restaurants might be built to encourage visitors to linger, in the process creating a sort of Cleveland Ponte Vecchio.

About the Author: Tom Matowitz

Recently retired after a 37-year career teaching public speaking, Tom Matowitz has had a lifelong interest in local and regional history. Working as a freelance author for the past 20 years he has written a number of books and articles about Cleveland’s past. He has a particular interest in the area’s rich architectural history.