Wilbur J. Watson, designer of the region’s most elegant and functional concrete bridges

Civil engineer and Northeast Ohio native Wilbur J. Watson not only set the standard for bridge construction across the country, he is also known for building some of the most beautiful bridges in Cleveland.

Born in Berea on April 5, 1871, Watson was educated in Cleveland and spent his professional career working here. He was trained as a civil engineer and held a B.S. from the Case School of Applied Science (later becoming Case Institute of Technology and eventually Case School of Engineering).

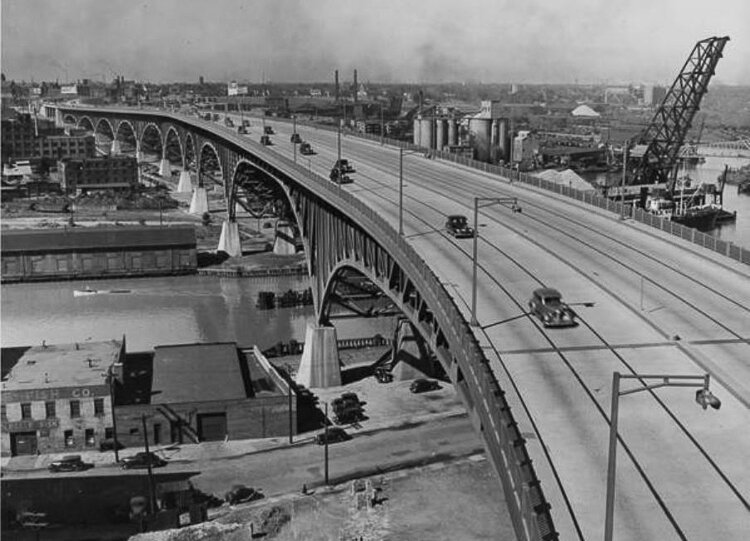

Main Avenue Bridge Construction, 1939Watson was highly regarded as a bridge designer—creating structures that combined aesthetics and engineering in a way that led to some of the most elegant and functional bridges in Northeast Ohio.

Main Avenue Bridge Construction, 1939Watson was highly regarded as a bridge designer—creating structures that combined aesthetics and engineering in a way that led to some of the most elegant and functional bridges in Northeast Ohio.

Starting his career with Osborn Engineering, Watson began designing bridges in 1898, several years before he even turned 30 years old.

Founded in July 1892, the Osborn firm is the oldest engineering firm in Cleveland—having been in continuous operation for nearly 130 years. Founded by Frank C. Osborn, the firm had an excellent bridge building pedigree given that Osborn was formerly chief engineer of Cleveland’s King Iron Bridge Company—the largest highway bridge company in the United States in the 1880s and developer of the metal truss bridge.

The first decade of the 20th Century was a significant time in Watson’s life. He married Harriet Barnes in 1900. Seven years later he struck out on his own, founding Wilbur J. Watson & Associates in 1907.

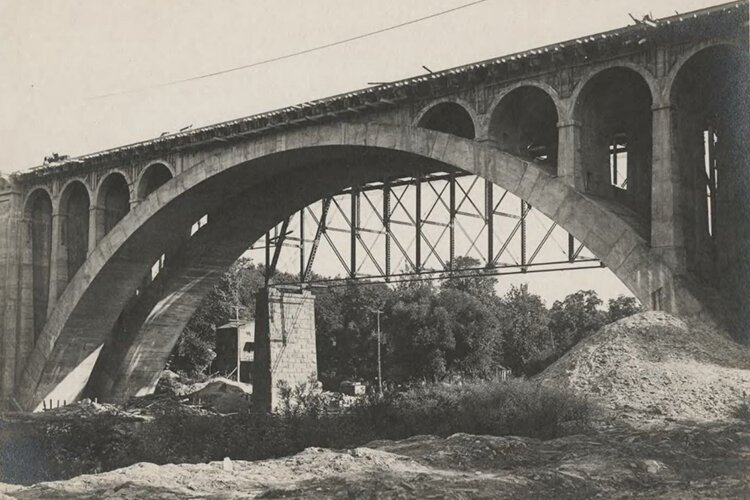

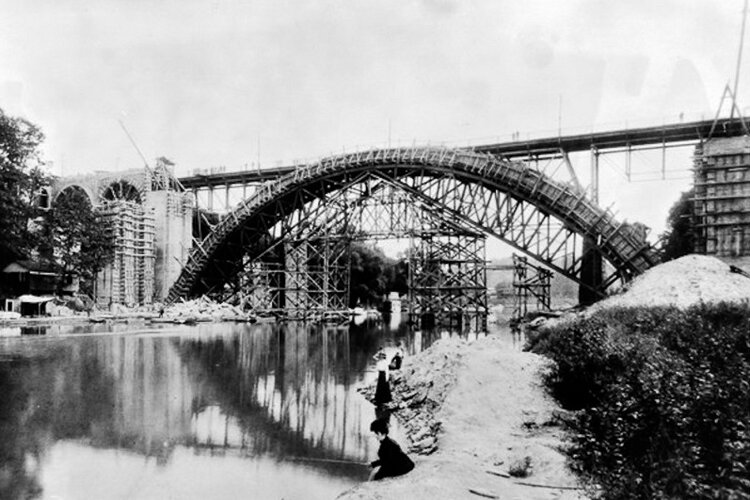

The 1910 Detroit Rocky River Bridge Construction, 1909Watson quickly pioneered several innovations in design, such as precast concrete beams and steel centering in the erection of concrete bridges. A notable example Watson’s concrete bridges is the 1910 Detroit-Rocky River Bridge, which spanned the Rocky River valley on a series of graceful arches for 75 years.

The 1910 Detroit Rocky River Bridge Construction, 1909Watson quickly pioneered several innovations in design, such as precast concrete beams and steel centering in the erection of concrete bridges. A notable example Watson’s concrete bridges is the 1910 Detroit-Rocky River Bridge, which spanned the Rocky River valley on a series of graceful arches for 75 years.

Built of built of concrete and steel, the Detroit-Rocky River Bridge was the longest stretch of unreinforced concrete in the world at the time, measuring 208 feet.

When the bridge began to deteriorate, a new bridge was built, and Watson’s bridge was demolished in 1980. The west piers of Watson’s bridge remained intact—and they now serve as the foundation for the Bridge Building in Rocky River.

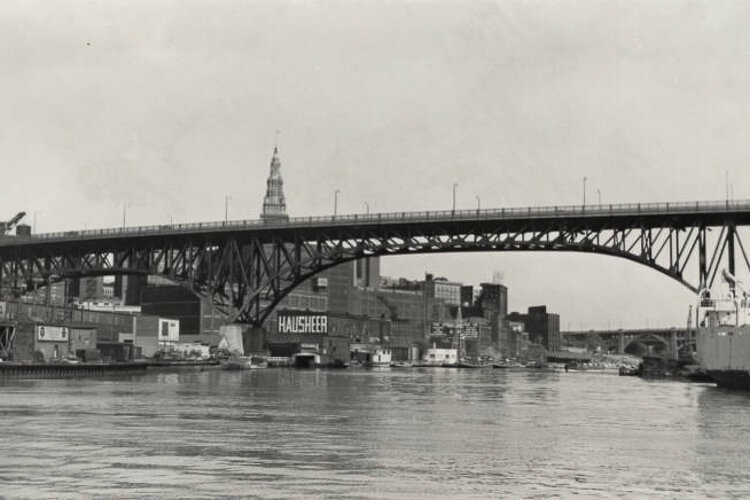

Watson’s later work includes both the Main Avenue Bridge and Lorain-Carnegie Bridge (today, the Hope Memorial Bridge) in Cleveland—both dating from the 1930s.

The Main Avenue Bridge is 8,000 feet long, making it the longest elevated structure in Ohio. Watson’s 1939 bridge is the third one this site. It replaced an early swing bridge built in 1869, thereby eliminating a choke point for river traffic.

The present Main Avenue bridge was built over a 17-month period at a cost $7.5 million—and five human lives.

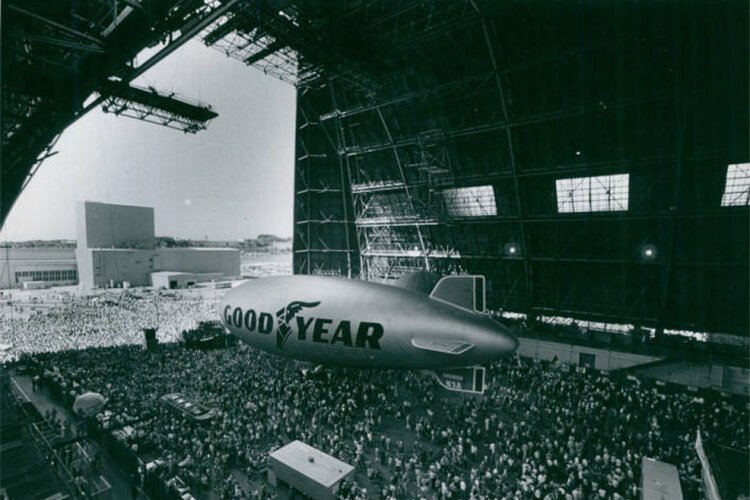

Goodyear Airdock, Akron, 1986Watson’s work was not confined to bridges. In Akron he designed the 1929 Goodyear Zeppelin Airdock. This enormous building covers eight-and-a-half acres, making it the largest uninterrupted interior space in the world.

Goodyear Airdock, Akron, 1986Watson’s work was not confined to bridges. In Akron he designed the 1929 Goodyear Zeppelin Airdock. This enormous building covers eight-and-a-half acres, making it the largest uninterrupted interior space in the world.

The airdock was built to service rigid airships built by Goodyear for the United States Navy. Two rigid airships were built by the firm: The U.S.S Akron and the U.S S. Macon. Both were lost in disastrous accidents by 1935. Their former hangar continues to be used today, an extraordinary and unmistakable artifact from U.S. aviation’s Golden Age.

Watson wrote several well received books on the subject of bridge design and construction. His final book was “Bridges in History and Legend,” written with the assistance of his daughters Emily and Sara Ruth and published in 1937.

Two years later Watson died at the age of 68 on May 22, 1939.

About the Author: Tom Matowitz

Recently retired after a 37-year career teaching public speaking, Tom Matowitz has had a lifelong interest in local and regional history. Working as a freelance author for the past 20 years he has written a number of books and articles about Cleveland’s past. He has a particular interest in the area’s rich architectural history.