Woodland Cemetery: An early example of a garden cemetery

Early American cemeteries were stark and forbidding. Made up of orderly rows of tombstones and generally devoid of landscaping, they were not places where people were inclined to linger.

In the mid-19th Century, that landscape began to change with the advent of what are known as garden cemeteries—rural landscaped cemeteries located outside a city’s urban core. An early example in the United States was Mount Auburn Cemetery in Cambridge, Massachusetts.

Mount Auburn was characterized by winding paths and carriage drives combined with elaborate landscaping. It provided inviting surroundings for mourners to reflect on and enjoy.

Here in Cleveland, one of the earliest examples is Woodland Cemetery in today’s Central neighborhood. Created in 1853, it was located on property the city had purchased two years earlier.

Here in Cleveland, one of the earliest examples is Woodland Cemetery in today’s Central neighborhood. Created in 1853, it was located on property the city had purchased two years earlier.

It was inspired by Cleveland’s growth—both geographically and in terms of population. It was obvious that an early cemetery like the 1826 Erie Street Cemetery wouldn’t be able to meet the city’s needs much longer.

Woodland Cemetery blazed a trail as the first garden cemetery of its type in Cleveland, predating both Lake View and Riverside Cemeteries by 15 to 20 years.

It contains interments that recognize a wide cross-section of Cleveland residents, from political leaders as to people involved in about every controversy of the 19th Century.

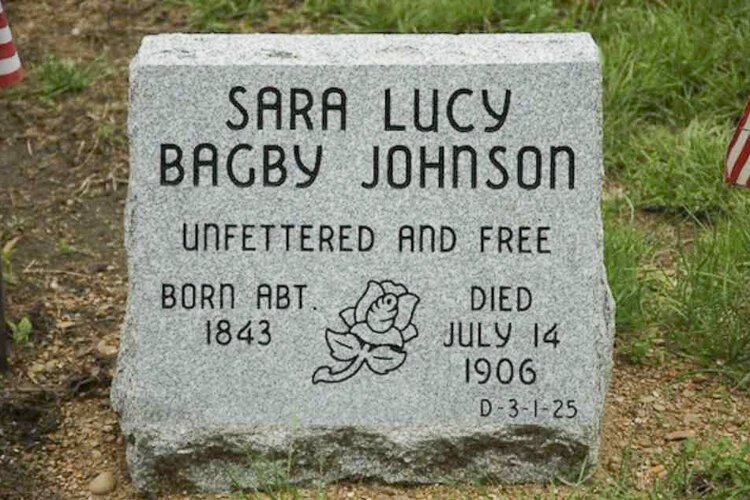

Carrie CliffordA perfect example is Sara Lucy Bagby Johnson, the last person prosecuted under the Fugitive Slave Act. The cemetery provides a last resting place for several prominent members of the Underground Railroad and even a well-known African American poet, Carrie Williams Clifford.

Carrie CliffordA perfect example is Sara Lucy Bagby Johnson, the last person prosecuted under the Fugitive Slave Act. The cemetery provides a last resting place for several prominent members of the Underground Railroad and even a well-known African American poet, Carrie Williams Clifford.

Cleveland’s first chief of police, John N. Frazee was buried in Woodland in 1917.

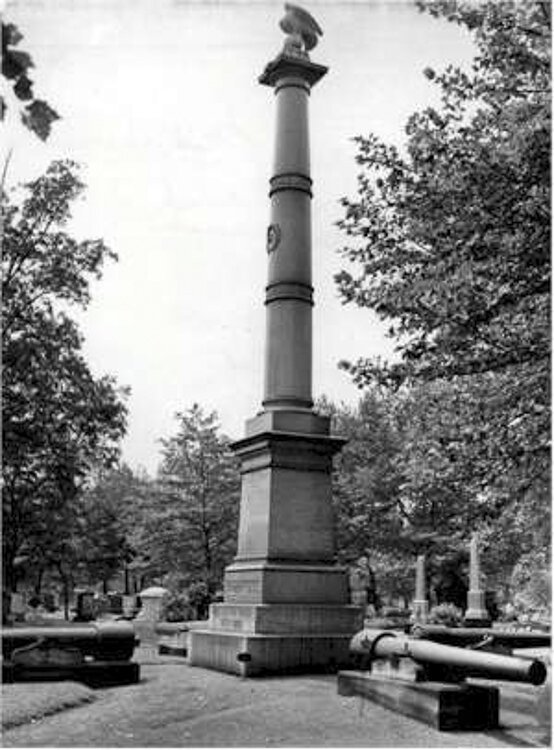

While Woodland hosts one of the earliest Civil War monuments in the United States—a memorial to the 23rd OVI erected in 1865—it was recently updated with a monument to honor 86 Black Union veterans buried there.

The cemetery even shelters the remains of a single veteran of the Confederate Army.

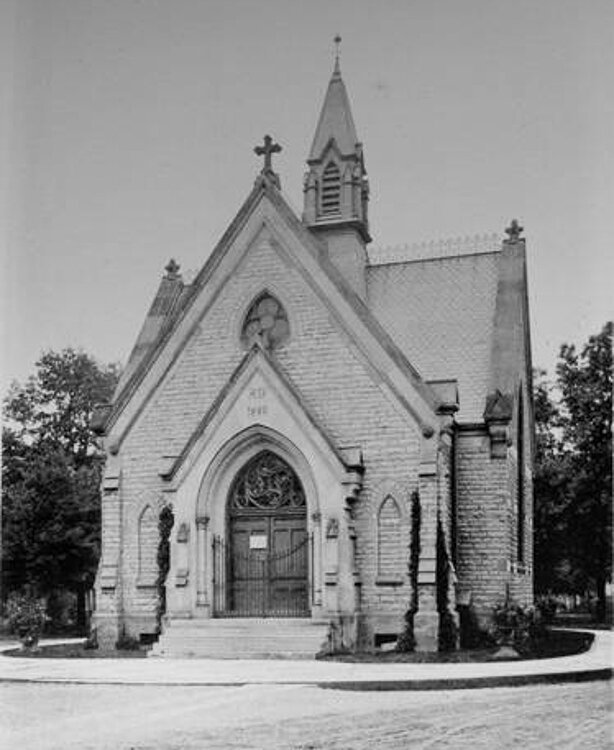

By the late 19th Century, the cemetery was embellished by a stone gatehouse, substantial landscaping, and elaborate iron fencing, as well as intricate tombstones in every style.

John Brough, the last Ohio Civil War governor, was buried in 1865 at Woodland.In addition to military figures the cemetery guards the remains of major political figures such as John Brough, newspaper publisher and Ohio’s Civil War governor. Another notable burial is the body of once-renowned Cleveland architect J. Milton Dyer, remembered as the designer of Cleveland City Hall.

John Brough, the last Ohio Civil War governor, was buried in 1865 at Woodland.In addition to military figures the cemetery guards the remains of major political figures such as John Brough, newspaper publisher and Ohio’s Civil War governor. Another notable burial is the body of once-renowned Cleveland architect J. Milton Dyer, remembered as the designer of Cleveland City Hall.

With the advent of newer garden cemeteries Woodland’s popularity began to wane. When Lake View Cemetery was established in 1869 40% of its burials in the first year were reinterments from Woodland.

The establishment of new cemeteries like Highland Park and West Park at the turn of the 20th Century further undermined Woodland’s popularity.

Woodland suffered another blow in the early 1930s when a secretary was found to have embezzled $ 19,000—a very large sum of money at the time.

While the funds were recovered, this crime led to a lot of deferred maintenance.

By the mid-20th Century, changing demographics and World War II brought great changes to Woodland Cemetery.

Wartime scrap drives took many of the metal decorations the place was once noted for, and neglect and harsh Ohio winters wreaked havoc on once imposing stonework.

There was an interval when the cemetery had an air of abandonment. There was talk in the early 1950s of closing the cemetery and relocating all the graves to make way for a city housing project. Public opinion strongly rejected this.

Concerned citizens who are part of the Woodland Cemetery Foundation who understood its significance refused to allow Woodland to pass into history.

A grass roots movement to restore Woodland began at the turn of the 21st Century and continues to this day. Recent improvements include reconstruction of the original stone gate house that had fallen into disrepair.

After considerable effort, the cemetery is once again a showplace—a proud setting for the multitude of Cleveland history it offers to visitors.

About the Author: Tom Matowitz

Recently retired after a 37-year career teaching public speaking, Tom Matowitz has had a lifelong interest in local and regional history. Working as a freelance author for the past 20 years he has written a number of books and articles about Cleveland’s past. He has a particular interest in the area’s rich architectural history.