Zenas King: Built the bridges that connect Cleveland’s east and west sides

From the region’s earliest days, the Cuyahoga River has been both a thoroughfare and an obstacle. A means of crossing it that didn’t obstruct late 19th Century river traffic posed a dilemma.

Zenas King contributed to the answer by founding a company that built three major bridges across the Cuyahoga River.

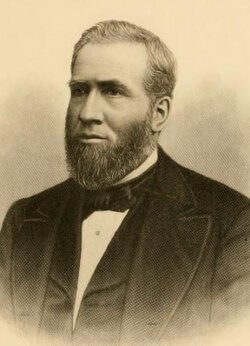

Zenas KingKing was a native of Vermont, born in the farm community of Kingston in the spring of 1818. He worked as a farm laborer until the age of 21 when he moved to Milan, Ohio to become a building contractor. Health issues lead to a career change, and he began to study the design and construction of iron bridges as early as 1858. He moved to Cleveland in the early 1860s.

Zenas KingKing was a native of Vermont, born in the farm community of Kingston in the spring of 1818. He worked as a farm laborer until the age of 21 when he moved to Milan, Ohio to become a building contractor. Health issues lead to a career change, and he began to study the design and construction of iron bridges as early as 1858. He moved to Cleveland in the early 1860s.

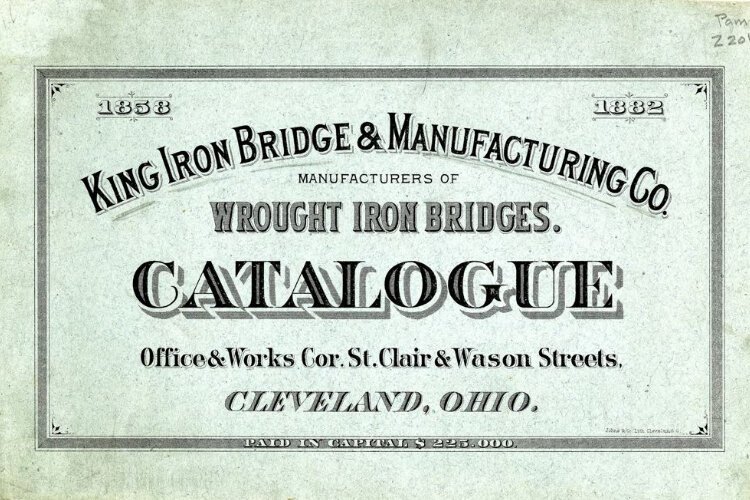

He established in 1871 the King Iron Bridge and Manufacturing Company in Cleveland, and shrewdly located his plant on a railroad line—greatly facilitating the shipping of bridge components to job sites.

King was responsible for several innovations in bridge design and became renowned for his sales and marketing ability. He established a network of agents to seek bridge building contracts and by the 1880s King Bridge and Manufacturing was the largest manufacturer of highway bridges in the United States. By the time of King’s death in 1892 his firm had constructed thousands of bridges across the United States.

The three bridge he built in Cleveland were innovative and well-designed in bridging the east and west banks of the Cuyahoga.

The Center Street Swing Bridge taken from the American Courage freighter with the Detroit-Superior bridge in the background.King Bridge built the Center Street Swing Bridge at Center Street and Merwin Avenue, the Central Viaduct which extends from West 14th Street to Carnegie Avenue, and the Detroit-Superior high level bridge (Veterans Memorial Bridge).

The Center Street Swing Bridge taken from the American Courage freighter with the Detroit-Superior bridge in the background.King Bridge built the Center Street Swing Bridge at Center Street and Merwin Avenue, the Central Viaduct which extends from West 14th Street to Carnegie Avenue, and the Detroit-Superior high level bridge (Veterans Memorial Bridge).

Built in 1901, the Center Street bridge is a rare example of a bobtail swing bridge—meaning the bridge pivots from one end rather than the center. This design was important in this location because of the necessity to avoid a pier that would obstruct the river channel. The bridge deck is 350 feet long by 24 feet wide.

Watching the bridge in action is fascinating—an alarm rings, the gates descend, and the deck begins to turn to a position parallel to the river. The movement is rapid and carefully balanced, functioning reliably almost 125 years after completion. The bridge is about to undergo an $8.6 million maintenance and renovation to insure its safe operation far into the future.

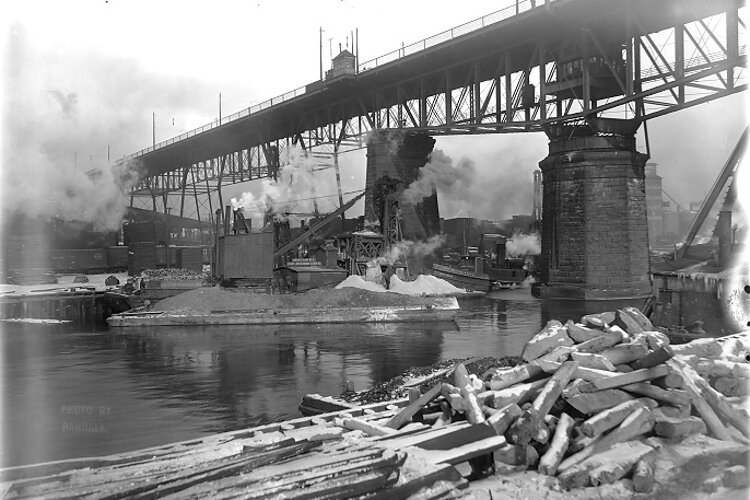

The Central Viaduct was the earliest of the three King bridges, having been constructed in the late 1880s. It was a steel structure positioned approximately where the Innerbelt bridge is located now. On a dark night in 1895 it was the scene of a terrible accident when a safety interlock failed—resulting in a streetcar filled with late-night commuters plunging without warning into the river and drowning 17 people.

The Central Viaduct was in bad condition by the early 1940s and was condemned and scrapped to supply steel for the war effort.

King Bridge’s most notable project is the Detroit-Superior Bridge. The 1878 Superior Viaduct had reached obsolescence by the 1910s, with its swing section a constant source of aggravation as the bridge closed for at least five minutes each time a ship passed by.

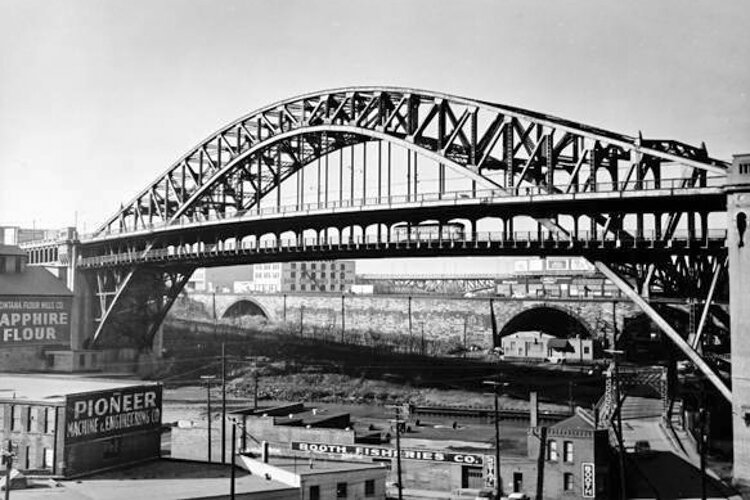

Detroit - Superior Bridge, shows streetcar travelling across lower deck.The new Detroit-Superior bridge formed a graceful arch that rose high above the river and posed no obstacle to river traffic. An unusual aspect was the streetcar tracks that ran below the bridge’s deck. This feature included passenger stations at each end—all of which closed in 1954 when streetcars disappeared from Cleveland streets.

Detroit - Superior Bridge, shows streetcar travelling across lower deck.The new Detroit-Superior bridge formed a graceful arch that rose high above the river and posed no obstacle to river traffic. An unusual aspect was the streetcar tracks that ran below the bridge’s deck. This feature included passenger stations at each end—all of which closed in 1954 when streetcars disappeared from Cleveland streets.

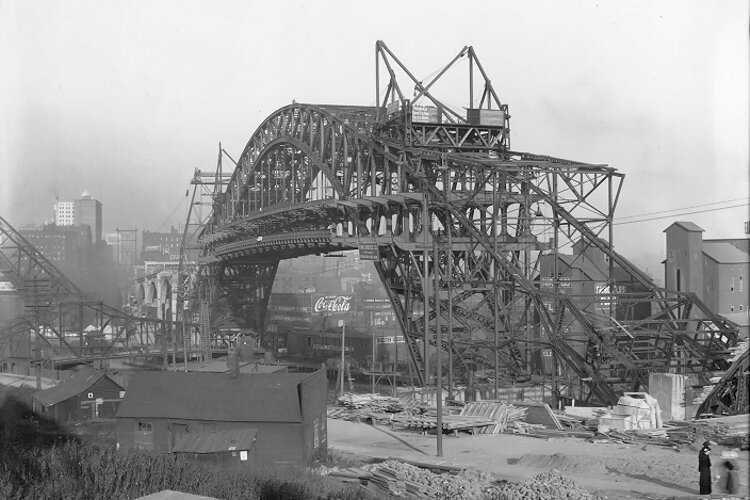

The Detroit-Superior bridge was under construction for five years, ending with its dedication on Thanksgiving Day 1917. The bridge cost $5 million to build a century ago. The equivalent cost today would be approximately $85 million.

Over 3,000 feet in length, the bridge was built outward from each bank, the structural steel being joined in the middle. While the two halves of the bridge failed to align exactly, this was anticipated and easily adjusted with winches and cables as the last rivets were set in place.

When the new bridge was completed, the Superior Viaduct was no longer needed. Explosives were used to bring down the offending swing section, ending an era in Cleveland history and transforming the remnant of the old bridge into a relic.

Representing two different technologies and approaches to bridge design, the surviving King bridges remain in excellent condition in daily use more than a century after they were built.

About the Author: Tom Matowitz

Recently retired after a 37-year career teaching public speaking, Tom Matowitz has had a lifelong interest in local and regional history. Working as a freelance author for the past 20 years he has written a number of books and articles about Cleveland’s past. He has a particular interest in the area’s rich architectural history.