The National Air Races: The ace pilots who drag raced the skies before the start of WWII

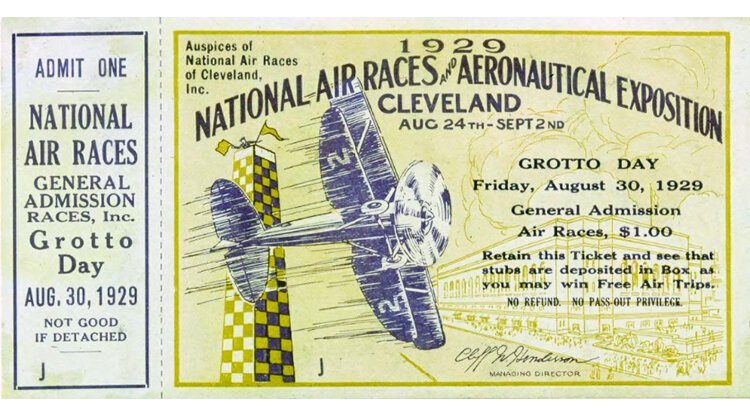

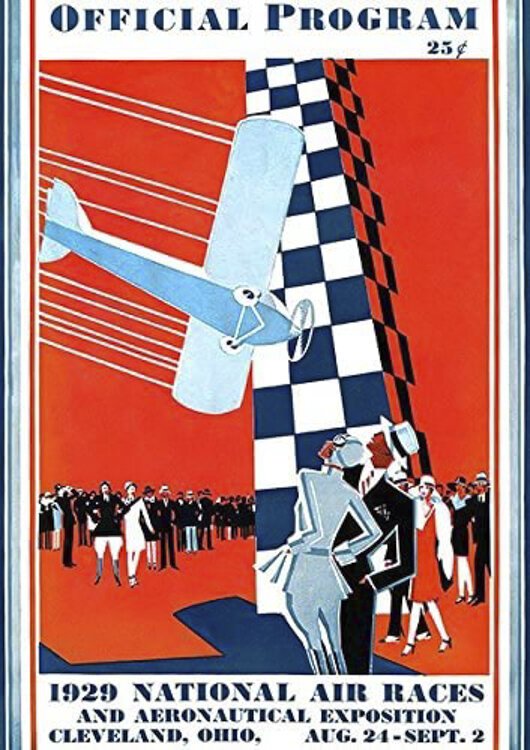

Aviation history was written in Cleveland from 1929 through 1949 when the city hosted the National Air Races over Labor Day weekend—an event so popular that it frequently drew a daily crowd of 100,000 spectators during some of the grimmest years of the Great Depression.

Part of the draw was the Cleveland Municipal Airport (today Cleveland Hopkins International Airport). Located at the intersection of Rocky River and Riverside Drives on the city’s far southwest side, this 1,000-acre facility was established in 1925 to accommodate airmail flights.

Cleveland was a stop along the transcontinental airmail route that connected New York City with San Francisco. The new airport’s first official flight operation was the landing of a De Haviland DH-4B mail plane, arriving from the west on the evening of May 1, 1925.

The airport was the largest anywhere in the world at the time, and Cleveland was home to several major aviation-themed businesses.

The airport was the largest anywhere in the world at the time, and Cleveland was home to several major aviation-themed businesses.

The Glenn Martin Company and Great Lakes Aircraft Company built airplanes in Cleveland, while Thompson Products (which later merged to become TRW) and Cleveland Pneumatic Tool (later Goodrich Landing Gear) manufactured vital aircraft components and sponsored prizes for the races.

The finest aviators in the world—both men and women—descended upon Cleveland for the Air Races event each year.

This event was largely the brainchild of master promoter Clifford Henderson. Starting from scratch, he created a world class event that drew attention from all over the world. The Air Races featured two major events—the Thompson Trophy Race and the Bendix Trophy Race. The Bendix Trophy involved a cross country race from Los Angeles to Cleveland. The Thompson Trophy was a pylon, or closed course race, that spectators could watch from the stands.

The airplanes were as colorful as their pilots. The vast majority of the prewar racing planes were homebuilt designs—original designs made specifically for air racing—as opposed to factory-built airplanes made in large numbers. These planes were so effective that they routinely outperformed the newest military designs. Examples include the Gee Bee Sportster,The Wedell-Williams racer, and the Howard racers.

The pilots were household names, and heroes to a generation of boys who grew up to fight World War II from the cockpits of Army Air Force, Navy, and Marine aircraft.

Clevelander Blanche Noyes stands in front of her plane, "The Miss Cleveland," which she used in the 1929 Women's "Powder Puff" Air Derby.The pilots included names like Roscoe Turner and Jimmy Doolittle, Mary Haislip, Louise Thaden, and Jacqueline Cochran.

Clevelander Blanche Noyes stands in front of her plane, "The Miss Cleveland," which she used in the 1929 Women's "Powder Puff" Air Derby.The pilots included names like Roscoe Turner and Jimmy Doolittle, Mary Haislip, Louise Thaden, and Jacqueline Cochran.

One of the most renowned figures in U.S. aviation history, Doolittle won the 1932 Thompson Trophy Race at the controls of a Gee Bee Sportster, built in Springfield Massachusetts by the Granville Brothers and widely regarded as one of the most treacherous airplanes of its era.

The Gee Bee Sportster Doolittle flew was essentially a barrel shaped fuselage with enough wing area just to get off the ground. It was powered by a large radial engine and provided poor visibility for the pilot. The airplane was directionally unstable and built purely for racing. In the right hands it did this well, but most of the Gee Bee racers were lost in fatal accidents.

Roscoe Turner flew a Wedell-Williams racer for multiple Thompson Trophy victories—usually accompanied to the races by his pet lion, Gilmore.

Turner’s Wedell-Williams racer is on display at the Crawford Auto Aviation Museum.

The National Air Races came to an abrupt stop in September 1939 with the beginning of the war in Europe. When the races resumed in 1946, they were of a considerably different character. A new generation of pilots flew highly modified WW II surplus fighters—the prewar homebuilts consigned to memory.

The new generation included pilots like Cook Cleland and his team who flew Super Corsairs, dominating the postwar Thompson Trophy races. A P-51 Mustang flown in the postwar races is also At the Crawford Museum.

No one ever said this wasn’t dangerous. A young pilot on Cleland’s team, Tony Janazzo lost his life when he was overcome by carbon monoxide in the cockpit of his Super Corsair during the 1947 Thompson Trophy Race.

Aircraft accident at the 1932 Cleveland National Air RacesTwo years later the curtain rang down when Bill Odom lost control of a highly modified P-51C during the 1949 Thompson race. His airplane plummeted out of control into a residential neighborhood in Berea—killing Odom and a mother and child on the ground.

Aircraft accident at the 1932 Cleveland National Air RacesTwo years later the curtain rang down when Bill Odom lost control of a highly modified P-51C during the 1949 Thompson race. His airplane plummeted out of control into a residential neighborhood in Berea—killing Odom and a mother and child on the ground.

While other reasons have been cited as factors that ended these races, the tragic deaths resulting from this crash proved to be an unrecoverable public relations disaster.

Cleveland Police Chief George Matowitz commented that, from a public safety standpoint, continuing the races could not be justified and many local municipalities enacted ordinances forbidding air racing in the skies overhead.

The races vanished, not to return until creation of the Cleveland National Air Show in 1964, creating an event that is directly descended from Cliff Henderson and the 1929 Cleveland National Air Races.

The popular Thunderbird exhibition was canceled in 1981 because of an accident in a Northrop T-38 Talon jet—birds ingested into the engines on takeoff caused engine failure. Subsequent Thunderbird performances for decades involved airplanes flying from Cleveland Hopkins over Burke without ever landing at Burke.

The Cleveland National Air Show continues today, with this year’s show—complete with Thunderbirds—scheduled for Labor Day weekend, Saturday, Sept. 4 through Monday, Sept. 6 at Burke Lakefront Airport.

Tickets are only available online. There will be no tickets sold at the gate.

For more information on the National Air Races, read Tom Matowitz's book "Cleveland's National Air Races."

(Editor’s note: Cleveland police Chief George Matowitz was Tom Matowitz’s grandfather).

About the Author: Tom Matowitz

Recently retired after a 37-year career teaching public speaking, Tom Matowitz has had a lifelong interest in local and regional history. Working as a freelance author for the past 20 years he has written a number of books and articles about Cleveland’s past. He has a particular interest in the area’s rich architectural history.