Just add mushrooms: How the Hulett Hotel could spawn other new construction in Ohio City

For most people, mushrooms bring to mind a pizza topping or another culinary dish (or even an invasive lawn growth). But Chris Maurer, principal architect and founder for redhouse studio in Ohio City, sees mushrooms—or mycelium, the organism that sprouts to fruit mushrooms—and thinks building materials.

In fact, Maurer and his team have translated that vision into an innovative way to recycle debris from demolished homes and buildings. His approach turns mycelium into biomaterial that can be used to rebuild in disaster zones, save millions of tons of debris from landfills, or even take debris from the renovation of a 19th century building on W. 25th for the proposed Hulett Hotel and create a new storage shed for Refugee Response and Ohio City Farm.

“Cleveland is ground zero for biocycling,” says Maurer, citing projects like the hotel or the approximately 9,000 abandoned and condemned houses that have been demolished in Cleveland since 2006.

All that debris could be used to recycle demolished structures into new construction—using mycelium.

“In a nutshell, we use mushrooms to turn old building into new buildings,” says Maurer. “We take organic materials from demolition—two-by-fours, wood sheeting, some insulation, and sometimes drywall—and chip it into smaller pieces, innculate that substrate with micro-organisms and fungi, and grow new materials. We then make forms out of acrylic or wood coated in plastic and make any shape of building material out of it.”

Maurer’s dream is to incorporate this process into a construction standard, saving more than 534 million tons of construction waste each year from landfills and instead recycling that debris into building materials (or "bioterials").

His first proof of concept will soon come with the proposed construction of the Hulett Hotel at 1468 W. 25th St. in Ohio City. Designed by Maurer for Cleveland Hostel owner Mark Raymond, the 19th century, three-story building will require some demolition work to retrofit and create the look of mechanical ore unloaders invented by George Hulett.

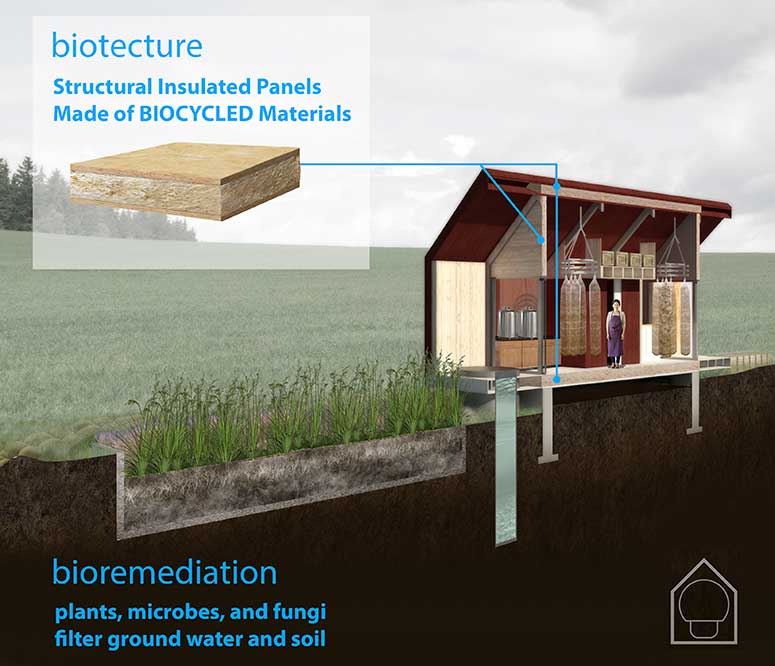

Maurer plans to take the debris from the Hulett, create bioterials, and build a 200-square-foot shed structure for Refugee  Response. He will then create structural insulating panels (SIPs) to form the floor, walls, and roof of the building, while using commercial weather barriers and some metal brackets to join the SIPs. As Maurer sees it, the shed could be used for storage and eventually even a growing house for mushrooms—a possible cash crop for Ohio City Farm and Refugee Response.

Response. He will then create structural insulating panels (SIPs) to form the floor, walls, and roof of the building, while using commercial weather barriers and some metal brackets to join the SIPs. As Maurer sees it, the shed could be used for storage and eventually even a growing house for mushrooms—a possible cash crop for Ohio City Farm and Refugee Response.

He estimates the whole structure should only cost about $10,000, not including research and development. Maurer's goal is to raise $25,000 for the project, which would also include a battery of tests to prove the construction is safe and effective.

One of the question marks is how long the project will take. “This proof-of-concept project will help understand the timelines,” explains Maurer. “We are certain, however, that these processes would help expedite relief in that they will clear debris and may lead to the production of entire structures ‘grown’ on site.”

Refugee Response executive director Patrick Kearns is intrigued by Maurer’s proposal. “We always need space,” he says, adding that they would first use the shed for storage and then consider using it to grow mushrooms.

Maurer's inspiration was derived from MycoWorks Phillip Ross’ work with mycelium, and that vision was strengthened by further research confirming the resilience of building materials created out of recycled material and mycelium.

“Tests that we and other researchers have conducted show that these easily-formed bioterials have compressive strength similar to wood framing,” says Maurer. “Their bending strength is better than concrete, and their insulation value is better than fiberglass batts.”

That knowledge sent Maurer on a humanitarian mission. “Imagine if there was a way to build directly from the ruins,” Maurer says in a video he made for a recent unsuccessful Kickstarter campaign to raise $25,000 for a mobile recycler station for creating bioterials. His goal was to take the mobile recycler around the country to different construction or disaster sites to illustrate the approach's efficiency and effectiveness.

“It will be much cheaper and more environmentally sustainable to rebuild this way,” Maurer explains. “We are advocating using trash as the building material and microorganisms as the laborers—neither require much money or carbon expenditure."

Of course, Maurer still needs the funding to build not only the shed, but his mobile biocycler and eventually bioshelters around the world made using mycelium-based materials. “It’s not technical at all and can be used in the developing world very easily,” he says of the practice.

Larger organizations have taken notice of Maurer’s work. Right now, he has proposals out to University of Akron and has talked to NASA and MIT about mycelium’s possibilities. “MIT [sees] the possibility of food security, and NASA sees [mycelium] as a resource for building off-planet,” he says, adding that the uses of bioterials reach into devices like smoke detectors and cell phones and even medical applications. “We’re looking at making a more sophisticated material that can be grown anywhere.”

Like right here in Ohio City.