New hope for historic Scofield Mansion restoration

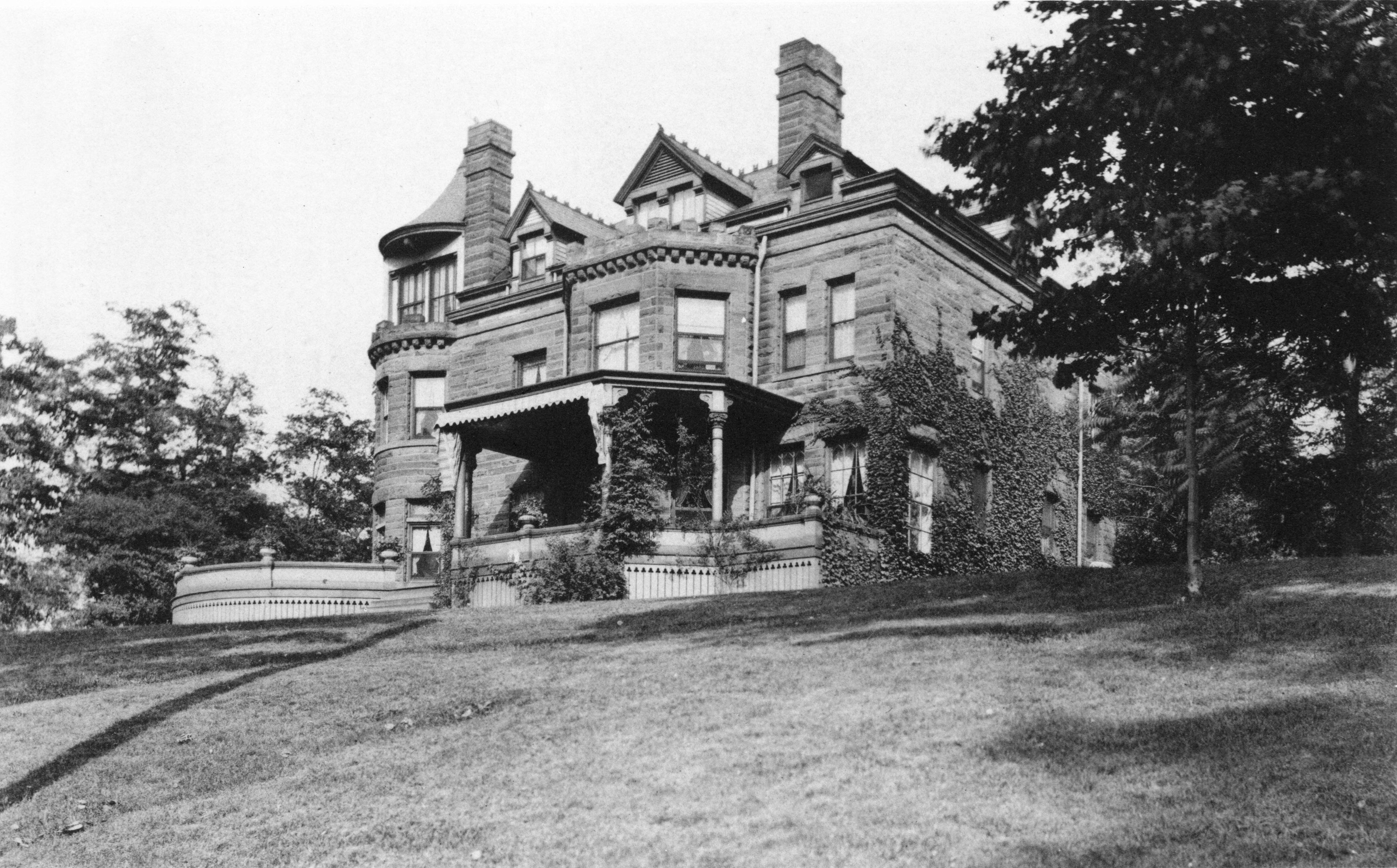

The 1898 dilapidated mansion of renowned Cleveland architect Levi Scofield is about to get a makeover and a new chance to become a crown jewel of the Buckeye Woodhill neighborhood, thanks to the valiant efforts of the Cleveland Restoration Society (CRS), Cleveland Neighborhood Progress, the Cuyahoga County Land Bank and a team of volunteers.

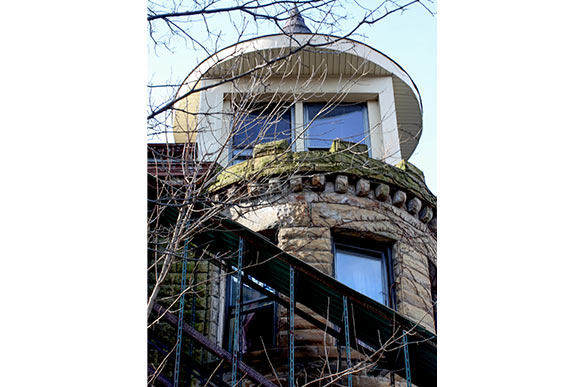

Scofield’s vacant historic home, tucked away at 2438 Mapleside Road, has fallen into disrepair over the past two decades.

“It’s in a forgotten corner of this neighborhood, in an area you wouldn’t normally go to,” says CRS president Kathleen Crowther. “It’s like a haunted house. But if it’s restored and sold, it could be a showcase for the city and could really turn this neighborhood around.”

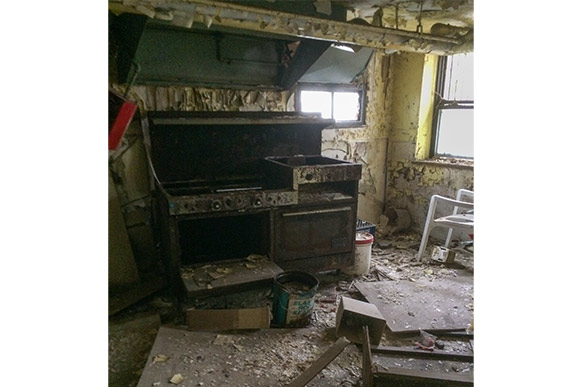

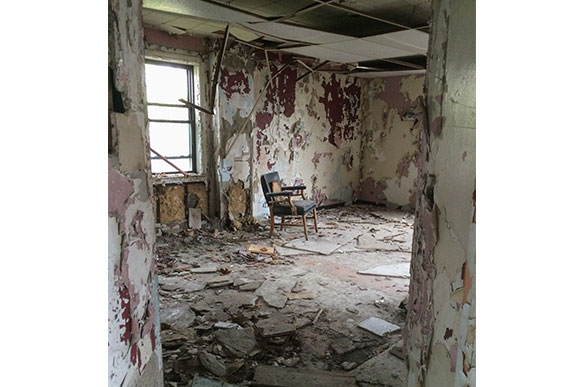

That optimism is why the CRS formed a blue ribbon task force last year with the hope of saving and restoring the home. “This is a last-ditch effort on this property,” Crowther says, noting the structure has been flagged for potential demolition. “It’s completely open to the elements, kids can get in there. It’s horrible. It’s now or never.”

Despite the repairs needed because of vandals and exposure, Crowther says the house is structurally sound. “The stone is Berea sandstone, the wood is hard as steel,” she says, adding that the original slate roof is still intact. “The wood that was used back then was hard, dense lumber. The building was very well-built.”

Saving the mansion is now looking like a possibility, as the property could be signed over to the Land Bank as earlier as the end of this week, says Justin Fleming, director of real estate for Neighborhood Progress.

The move was made possible through a legal deal in which the current owner agreed to donate the property to the Land Bank in exchange for the court waiving $55,000 on back property taxes. In turn, the Land Bank has agreed to hold the property for two years while Neighborhood Progress and the task force try to save the house.

“We’ve been working on it in earnest since last spring and not it’s really all hands on deck,” says Fleming of the effort. “This gives us time to clean it out, stabilize it and secure the house and really set the stage for what could happen.”

When Scofield, who is best known in Cleveland for the Soldiers and Sailors Monument in Public Square and the Schofield Building, now the Kimpton Schofield on E. 9th, was looking to move to the country in the late 1890s, he bought six acres of land on a bluff overlooking the Fairmount Reservoir and built the 6,000-square-foot, three-story Victorian home.

“It was designed in a very picturesque setting to overlook the city,” says Crowther. “He built it in a bucolic area to have magnificent views of the city.”

After Scofield’s death in 1917, his family remained in the house until 1925. Over the years the house served as a chapel, a convent, and finally a nursing home until 1990. Sometime in the 1960s, a second building was erected on the land as an extension of the nursing home.

Both buildings stood vacant and went into disrepair since 1990. In 2011 a buyer, Rosalin Lyons, bought the property for $1,400 at a foreclosure auction, thinking she was just buying the 60s building. But the sale included the mansion, according to Fleming.

“I can understand the thought process on the building because it has really good bones,” he says. “But Lyons was in way over her head and nothing ever happened to either property.”

Crowther says the owner had plans to transform the property into a rehab center, but nothing every came of it and Lyons ended up in housing court. “She had dreams of doing something good for the community there but that dream needed money,” Crowther says. “She was between a rock and a hard place.”

Now members of the task force are making preparations for stabilization work on the house as soon as they get the word the transfer is complete. “The clean-out, the stabilization and securing of the house really sets the stage for what could happen,” proclaims Fleming. “Let’s save the asset.”

Three companies have already committed their time, labor and services to stabilize the house, says Crowther, who calls the process “mothballing,” which means preserving the property for future renovations.

Joe DiGeronimo, vice president of Independence-based remediation company Precision Environmental, has pledged to clean up both the mansion and a 1960s building built on the property. The DiGeronimo family has roots in the neighborhood, says Crowther, and has an interest in revitalizing the community.

“They have been heroes in this endeavor,” says Crowther of Precision Environmental.

Steve Coon, owner of Coon Restoration and Sealants in Louisville, Ohio, sits on the CRS board of trustees and has committed to roof and wall stabilization as well as masonry work. Cleveland-based SecureView will measure all of the doors and windows and fit them with the company’s patented clearboarding—clear, unbreakable material. The help is a relief for proponents of the renovation.

“In the beginning we were knocking out heads because we didn’t know what to do—there were so many pieces, all moving at the same time,” says Crowther of the project. “But inch by inch, we got somewhere.”

Crowther says CRS continues to raise money for the project. Once the building is stabilized, CRS and Neighborhood Progress will figure out the next steps in saving the house, marketing it and selling it. Both Crowther and Fleming say there is no concrete plan yet for the final outcome of the project, but they say they are pleased with the initial progress.

“I think it illustrates what can happen with lots of partners willing to come in and do something,” Crowther says.

John Hopkins, executive director of the Buckeye Shaker Square Development Corporation and task force member, says he sees restoring the Scofield Mansion as beneficial for the neighborhood in three ways.

“It would bring stability for the neighborhood,” says Hopkins. “It would not just stabilize the building, but stabilize the neighborhood. Second is the economic impact in that it would increase the value of some of the homes around it [the mansion]. Third, there will be a sense of pride in this great building we saved.”

Fleming says Neighborhood Progress must next bring in an architect to draft new floor plans for the home, as the originals are lost. “That will help us talk to a tenant,” he explains.

Eager to move forward, organizers on the task force are encouraged by the pending transfer.

“They are trying to save it as an anchor and a monument,” Fleming says. “The neighborhood deserves it. The house deserves it.”