clifton boulevard-style transit eyed for 25th street corridor

A study conducted by Cleveland Neighborhood Progress (CNP) and funded by the Cleveland Foundation and Enterprise Community Partners regarding the West 25th Street corridor (extending from the State Road intersection north to Detroit Avenue) has concluded that a dense residential neighborhood and reliable transit line go hand in hand.

The final report for the W. 25th Transit Oriented Development Strategy is due out at the end of this month, but Fresh Water got a preview from Wayne Mortensen, CNP's director of design and development.

"The study was designed to answer two sets of very critical interrelated questions. One being: what is the ultimate desired level of transit along corridor in terms of frequency, service and style?" says Mortensen, adding that the other focus was on the amount and type of area housing that would be required in order to support that transit and sustain it economically.

Wayne Mortensen

Wayne Mortensen

"West 25th is perhaps the most critical north/south connection in the city of Cleveland," he says of the 3.8-mile stretch, "and definitely for the West Side."

The group conducted three public meetings using eight different working groups, each of which focused on a separate issue including, commerce, education, housing, the pedestrian experience, recreation, services, transit and workforce.

"One of the most poignant points of feedback came from workforce group," says Mortensen. The group cited a hypothetical single mother, who might rely on public transit for daily stops at a daycare facility, a workplace and a grocery store. "She is relying on transit to be on time and efficient six to eight times a day. That's not something a lot of people in Cleveland understand or empathize with."

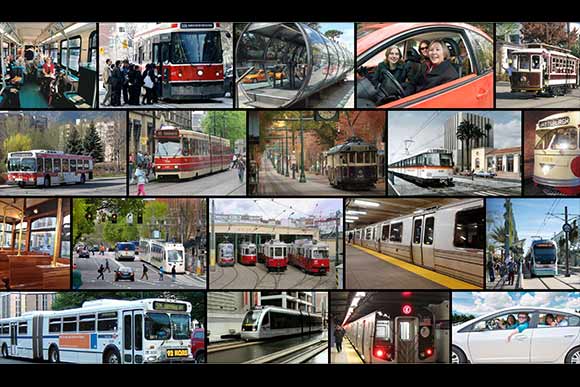

To meet those needs, the study concludes that a transit system similar to the Cleveland State Line, which runs along Clifton Boulevard, would be the best fit. Mortensen cites the line's frequency, improved waiting environments and a dedicated bus lane during certain times of the day. The line is also branded.

"So everyone knows when they hop on exactly where they're headed. It's more friendly in terms of way-finding and getting around the city," says Mortensen. "That's the closest example to what we think we can achieve.

"I want to be clear: we don't think of this as the next Euclid Health Line," he adds. "This is not as invasive or as capital intensive as what we see on Euclid."

In order to support transit efficiency similar to the Clifton Boulevard experience and keep that mom on time, a certain level of population density is required, which leads to the housing portion of the study.

"Depending on which part of corridor we're in," says Mortensen, "every housing project should be at least eight to 12 units per acre in terms of concentration density and be of an urban quality."

But is density desirable? That's a subjective question. It is, however, natural for areas such as the 25th Street corridor.

"Urban neighborhoods are more predisposed to attracting residents that have proactively--or just through the logistics of their lives have--foregone private transit," says Mortensen. Since people opt out of public transit for different reasons, they breed diversity in the urban communities they populate while creating a customer base for the public transit suppliers.

Committing to residential density leads to perhaps the most challenging implication of the study.

"It's going to be really important that all the community development corporations and communities work together and nobody develops projects along the corridor or within a ¼ mile that create less dense residential neighborhoods."

It's a tall order, one that Mortensen estimates could take up to 10 years.

"What's most important is patience by the community right now."