3D printing brings the sexy back to Cleveland's manufacturing sector

The manufacturing industry in Northeast Ohio has always carried a soot-stained appearance of dirty smoke stacks and imposing brick factories, Matt Hlavin knows.

Those days are finished, declares the CEO of Rapid Prototype + Manufacturing (rp+m), an Avon Lake company dedicated to the "printing" of three-dimensional solid objects from digital files, a process formally called additive manufacturing, but known in common parlance as 3D printing.

"Manufacturing is cool again; it's sexy," says Hlavin. "You can have facilities that look the same as any software company in Silicon Valley."

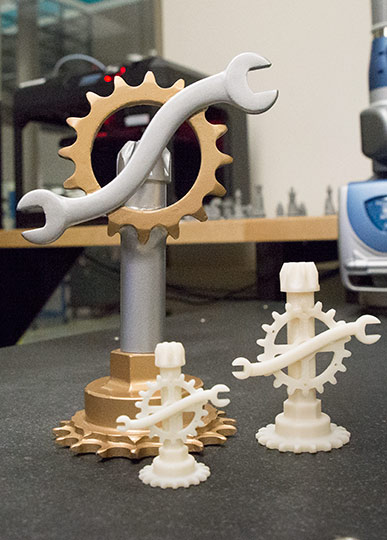

3D printing is ideal for complex projects requiring a high degree of customization, maintain proponents of a practice that takes ultrathin layers of plastic, steel or other materials and fuses them onto a flat surface, creating an exact three-dimensional replication of a digitally designed object.

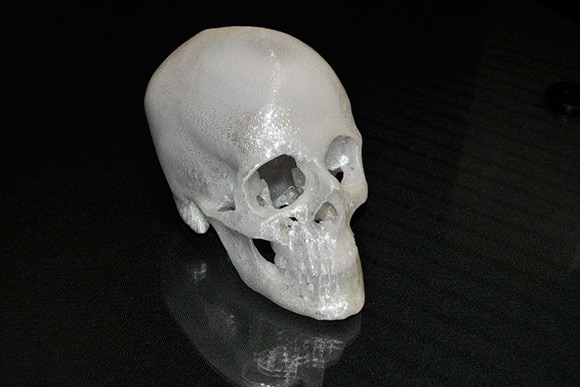

Rapid Prototype + ManufacturingFor example, rp+m recreates CT scans of human skulls with trauma injuries to aid surgeons in preparing for complex surgeries. The company, a spin-off of a family-owned plastic injection molding business, also makes single-piece aerospace solutions that would traditionally be assembled with a dozen or more total components.

Rapid Prototype + ManufacturingFor example, rp+m recreates CT scans of human skulls with trauma injuries to aid surgeons in preparing for complex surgeries. The company, a spin-off of a family-owned plastic injection molding business, also makes single-piece aerospace solutions that would traditionally be assembled with a dozen or more total components.

"We're creating shapes and geometries (on a computer) that don't exist," Hlavin says. "With 3D printing, it's a one-shot deal."

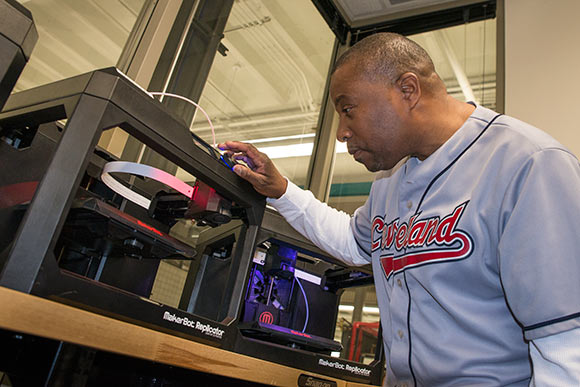

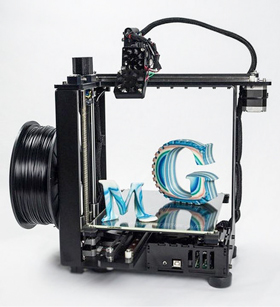

MakerGear founder Rick Pollack is always seeing something new and interesting within his chosen industry. Pollack, whose Beachwood-based company builds affordable 3D printers, points to the one-to-one creation of organs and blood vessels, or the ability of astronauts to print parts on demand from the reaches of outer space.

"The sweet spot for 3D printing is you can make a one-off part in short-run production," says Pollack. "You're not investing in the tooling up front, so you can make those parts relatively inexpensively."

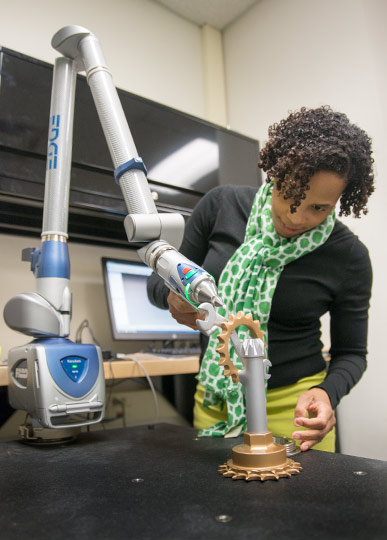

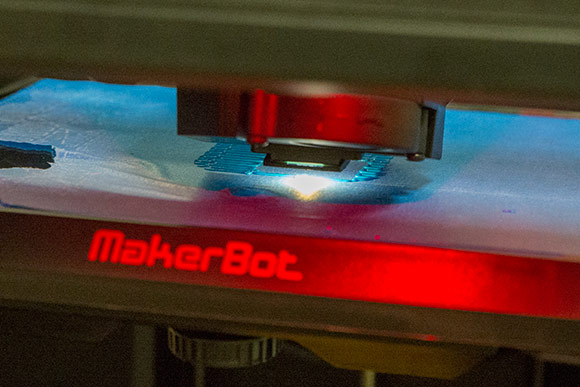

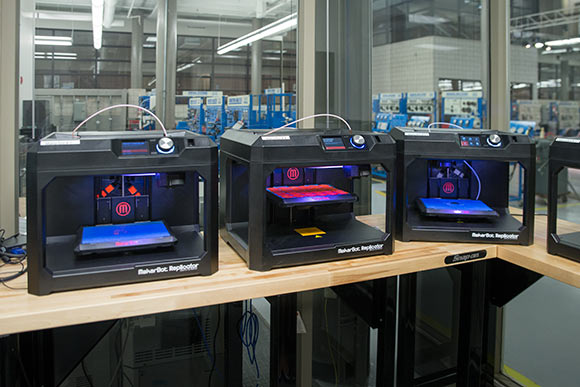

MakerGear 3D printerThe technology is often used to build prototypes or small quantities of tools and other products. Though the tech is not new - the first 3D printing innovations became visible in the late 1980s - those involved with the industry locally believe Northeast Ohio is ready to compete on a global scale when it comes to harnessing additive manufacturing for fabrication of parts that fit into real working products.

MakerGear 3D printerThe technology is often used to build prototypes or small quantities of tools and other products. Though the tech is not new - the first 3D printing innovations became visible in the late 1980s - those involved with the industry locally believe Northeast Ohio is ready to compete on a global scale when it comes to harnessing additive manufacturing for fabrication of parts that fit into real working products.

Fresh Water talked to a handful of Cleveland-area companies, universities and organizations excited about bringing sexy back to the region's changing manufacturing sector.

You say you want an evolution

Rp+m is a sister company of Thogus, a 65-year-old enterprise started by Hlavin's grandfather. A dedication to 3D printing has allowed Hlavin to minimize his supply chain and concentrate on improving or creating products not available through old-school manufacturing processes.

"3D printing is an evolution, not a revolution," he says. "Customers want suppliers with more solutions."

A recently founded partnership between rp+m and Case Western Reserve University could further push additive manufacturing into the mainstream, Hlavin believes. The company moved its research and development arm to the university last summer, where it joined forces with faculty researchers to develop new technologies and assist students interested in tech-related entrepreneurship opportunities.

Housed in a research laboratory in Case's department of material science and engineering, the partnership has been working to convert a laser hotwire welding technique into a 3D manufacturing process. The project is funded by America Makes, a Youngstown-headquartered institute created to scale up the use of 3D printing throughout the U.S.

Jim McGuffin-Cawley, chairman of the university's materials science and engineering department, believes the joint effort represents a natural extension of Northeast Ohio's already robust manufacturing base. In addition to in-house projects allowing students and rp+m staff to work side-by-side, the partners have discussed pursuing research grants and development deals with 3D printing companies both local and global.

"We're collaborating to develop technology that can be used in industry," says McGuffin-Cawley. "It's an experiment on both our parts, and it seems to be working so far."

Programs harnessing industry growth

The Case program is not just buoying research in a burgeoning field, it's also preparing students for a career in 3D design, says Hlavin. Though there has been much written about the role that high-level science, technology, engineering and math (STEM) skills will play in Cleveland's resurgent labor market, the tech-savvy entrepreneur would like to add an "A" to the mix - as in "arts."

3D printing in particular requires aesthetic values in the area of design. "These are skills you need to know for a new paradigm," Hlavin says. "Art is going to bring a different component (to additive manufacturing) outside of a broad-based, mechanical skill set."

Meanwhile, the operation of sophisticated 3D printing machines is going to require skilled technicians, says J. Craig McAtee, executive director of the 3D Digital Design & Manufacturing program at Cuyahoga Community College.

Chess Pieces printed at Tri-C's Unified Technologies Center at Tri-C

Chess Pieces printed at Tri-C's Unified Technologies Center at Tri-C

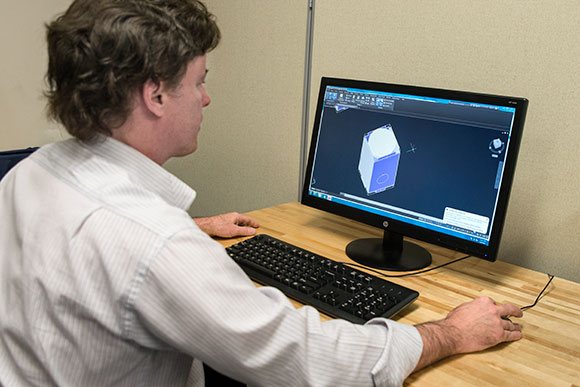

Under a grant from the U.S. Department of Labor, Tri-C launched a certificate program for individuals aiming to gain entry-level employment in careers related to additive manufacturing . Through the year, students learn to use Computer-Aided Drafting software (CAD), 3D scanners and printers, reverse engineering software, rapid prototyping, and Computer Numerical Control (CNC) programs.

The takeaway is a one-year certification that could land grads a job as a 3D designer, engineering technician, tech support specialist and more. Students also earn credit hours toward a two-year degree at Tri-C, or those credits may be transferred to a four-year college or university.

As 3D manufacturing is used in a variety of industries including aerospace, biomedical and automotive, local employment opportunities can be found at companies both large and small, McAtee says. "There's 40 companies involved with the technology regionally, either directly or indirectly," he says. "It's becoming a huge industry."

More than 35 percent of engineering professions need knowledge and skills related to 3D printing/additive manufacturing, notes McAtee, citing an April 2015 report from data company Wanted Analytics. According to national trends, 3D manufacturing will only get bigger. A 2014 report from consulting group Wohlers Associates, Inc. stated that the sale of 3D printed products and services will approach $6 billion worldwide by 2017, with those figures ballooning to almost $11 billion by 2021.

"Like other areas in technology, you need a pipeline of talent," says McAtee. "Many people still don't know what 3D printing or additive manufacturing are, but they see what's happening here and want to know more."

Manufacturing with a cool factor

MAGNET (Manufacturing Advocacy & Growth Network), a Cleveland-based manufacturing advocacy association, is partnering with Tri-C on its three-dimensional venture. Dave Pierson, a senior design engineer with MAGNET, is excited about a process that can build everything from robotic hands to economy-class airplane seats.

The upwards of 90 percent cost and time savings printing a quality steel part has over an ordinary stamped steel part may not have the same sex appeal as robots and comfy plane chairs, but it nicely illustrates the limitless possibilities presented by 3D design, Pierson says.

"To be competitive we have to look at the resources available in additive manufacturing and plug them into local area manufacturers," says Pierson. "If companies don't have their finger on the pulse of the industry, they're going to fall behind very quickly."

The tech has come a ways from decades-old stereolithography practices, when Pierson would send files by snail mail to California or New York and get back the finished part within a few weeks. Today, he can transmit a prototype design from his laptop to MAGNET's offices and have a part ready and waiting for him hours later. Young job seekers at Tri-C, Case or Lorain Community College's Fab Lab who want to operate outside the confines of traditional manufacturing now have the same opportunity, a thrilling proposition for a region trying to change its image.

"The industry is no longer a dull, oily, greasy environment where things gets made, like it was 20 years ago" Pierson says. "This is manufacturing with a cool factor."

![3D printing at Case Western Reserve's think[box]](/galleries/Features/2015/April_2015/Issue_207/3D_printing/3d_printing_csu-think-box_08.jpg)

![3D printing at Case Western Reserve's think[box]](/galleries/Features/2015/April_2015/Issue_207/3D_printing/3d_printing_csu-think-box_17.jpg)

![3D printing at Case Western Reserve's think[box]](/galleries/Features/2015/April_2015/Issue_207/3D_printing/3d_printing_csu-think-box_36.jpg)

![3D printing at Case Western Reserve's think[box]](/galleries/Features/2015/April_2015/Issue_207/3D_printing/3d_printing_csu-think-box_34.jpg)

![3D printing at Case Western Reserve's think[box]](/galleries/Features/2015/April_2015/Issue_207/3D_printing/3d_printing_csu-think-box_46.jpg)