The Allen-Sullivan House: Euclid Avenue Grande Dame takes its final bow

The story of one of Cleveland’s most colorful grand houses ended abruptly in June 2021, with the demolition of the Allen-Sullivan House (often mistakenly known as the Hall-Sullivan mansion), followed by Signet Real Estate Group’s groundbreaking on a new mixed-use residential project.

Located at what became 7218 Euclid Ave., this 1880s house sheltered two prominent Cleveland families for three decades.

This is the story of the mansion’s ascent to glory and its demise into eventual demolition—and the efforts to save a piece of Cleveland history.

The Queen Anne style Allen-Sullivan House at 7218 Euclid Avenue was built in 1887 for Richard N. Allen, the inventor of the paper car wheelThe beginning

The Queen Anne style Allen-Sullivan House at 7218 Euclid Avenue was built in 1887 for Richard N. Allen, the inventor of the paper car wheelThe beginning

The story begins in the mid-19th Century with the success of the railroad industry and the personal fortunes it created.

The earliest reference to a house on the future Euclid Avenue site of the Allen-Sullivan House comes in the 1850s. A house was built there for prominent Cleveland attorney Ephraim Estep. His reputation was such that future president James A. Garfield visited him in October 1875 to discuss forming a law partnership with him. Unfortunately, the house is not well documented and no images of it are known.

Estep’s house was sold to the Richard N.Allen family in the 1880s. The new owner made a fortune in the railroad industry, having patented an ingenious design for improving wheels on sleeping and dining cars on trains—providing a smoother and quieter ride for diners and passengers trying to sleep.

Allen earned his place on Euclid Avenue when it still held the reputation of being the most beautiful street in the world.

After living in the former Estep home for several years, Allen became dissatisfied with the house and had it demolished to make way for a new three-story Queen Anne style house.

One can only guess at the reasons for this decision. Allen’s choice may have represented an outdated architectural style, or the house may have become too small to accommodate his increasingly large extended family.

Whatever the reason, the original house was gone by the late 1880s, replaced by what would come to be known as the Allen-Sullivan House. A January 2000 Ohio Historic Inventory form indicates that the home was designed and built by an unknown architect and builder.

The new house towered over the property, with a large room on the top floor that was notable for an arrangement of windows that resembled the pilothouse of a Great Lakes freighter. The house included the turrets deemed necessary for decoration, a dramatic entryway with a large fireplace bordered by ceramic tile, and a substantial staircase leading to the upper floors.

The property was transformed into an unmistakable display of wealth, but upon Allen’s death in the early 1890s the house came up for sale. His widow, Susan, would later leave Cleveland for Massachusetts.

Jeremiah J. Sullivan, an Irish immigrant who came to America in 1850, owned and resided in the Allen-Sullivan House from 1898 until his death in 1922A transition

Jeremiah J. Sullivan, an Irish immigrant who came to America in 1850, owned and resided in the Allen-Sullivan House from 1898 until his death in 1922A transition

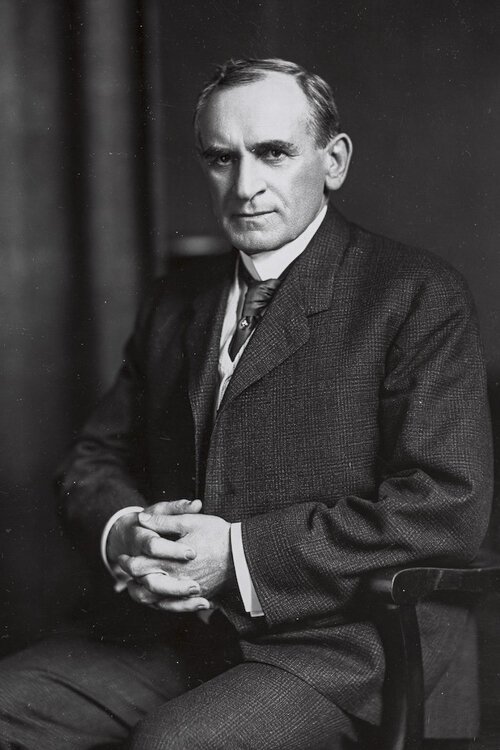

The new owner was Colonel Jeremiah J. Sullivan, a prominent Cleveland banker.

Sullivan was a classic immigrant success story. A native of Ireland, he came to America in 1844 at age 10. He gained what was known as a common school education and rose to importance early in life, becoming a state senator by 1879 when he was 35 years old. He was one of the organizers of the Soldiers’ and Sailors’ Home in Sandusky, where he also served as a trustee.

His interest in veterans affairs and later high rank in a local militia unit strongly suggests that Sullivan served in the Union Army in the Civil War.

Continuing to attract notice through his public service, he was selected by President Grover Cleveland to serve as a national bank examiner for Ohio in 1887.

Sullivan moved to Cleveland in the late 1880s and in 1890 he was one of the founders of Central National Bank of Cleveland. Ten years later, he was president of the bank and was involved in several prominent banking organizations.

Additionally, in 1905 Sullivan was president of the Cleveland Chamber of Commerce—the direct predecessor of the Greater Cleveland Growth Association (today the Greater Cleveland Partnership).

Sullivan was noted as one of a small number of influential bankers who supported the Federal Reserve Act of 1913 and was instrumental in bringing a Federal Reserve Bank to Cleveland.

Sullivan married Selina J. Brown in 1873. They shared the Euclid Avenue house with three children—Helen, Selma, and Corliss.

Sullivan died on February 2, 1922 and is buried in Lake View Cemetery.

Shortly after Jeremiah Sullivan’s death, the Sullivan family moved out of the home to an English cottage style property in Hunting Valley.

A place to shop, gather, and party

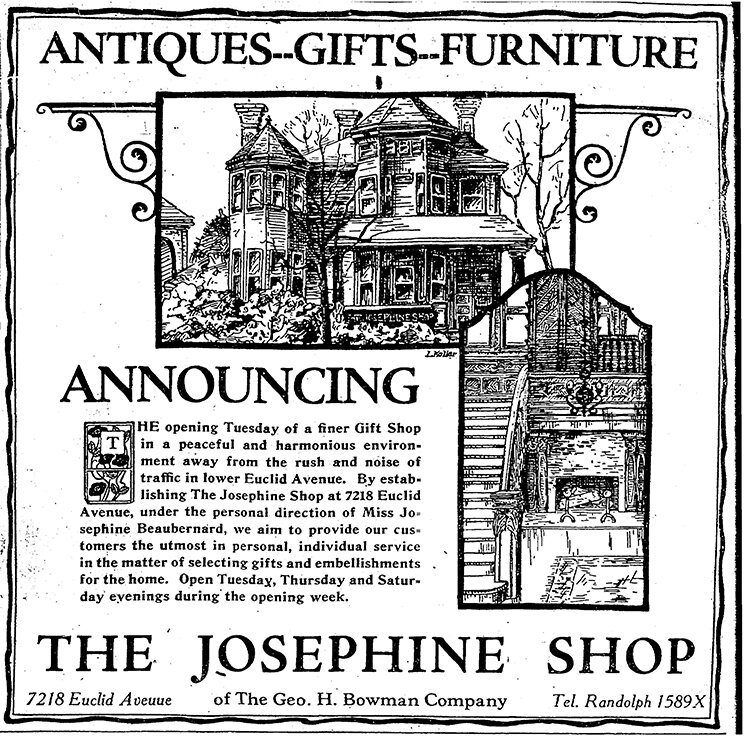

In 1923, Josephine Beaubernard transformed this once-grand residence into an equally grand home high-furnishings shop, known as the Josephine Shop and associated with the George H. Bowman Company, a fine furniture retailer in today’s Warehouse District.

Beaubernard routinely traveled to Europe to select high end merchandise to offer for sale in her shop. An ad published in the November 18, 1923 "Cleveland Plain Dealer" promoted its grand opening.

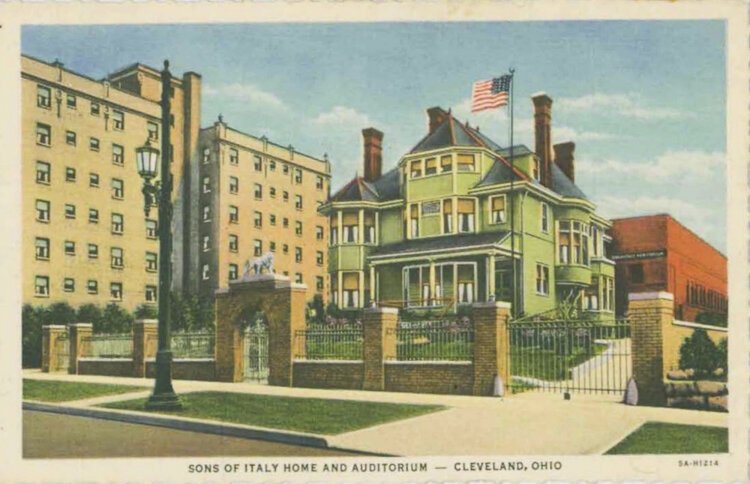

1935 circa postcard colorfully presents an image of the Allen-Sullivan House in the 1930s.By 1935 the house became Grand Lodge or Fraternal Lodge of Ohio, order Sons of Italy (SOI) in America, an Italian-American fraternal organization, providing a venue for events of great pride, as well as a platform for political controversy and incidents of illegal gambling.

1935 circa postcard colorfully presents an image of the Allen-Sullivan House in the 1930s.By 1935 the house became Grand Lodge or Fraternal Lodge of Ohio, order Sons of Italy (SOI) in America, an Italian-American fraternal organization, providing a venue for events of great pride, as well as a platform for political controversy and incidents of illegal gambling.

By 1933, 30 senior and 10 junior branches of the order developed in Cleveland—making the need for a grand lodge pertinent for SOI branch members to meet.

Frank Azzerelli was the architect of the auditorium added to the rear of the house. The addition cost $75,000 to build and could seat up to 200 people.

The June 2, 1935 dedication ceremony held by SOI was attended by 25,000 local, state, and foreign dignitaries. The Italian ambassador, Augusto Russo, visited Ohio for the first time. A grand ball was held in the newly built auditorium in Russo’s honor for his two-day visit in Cleveland.

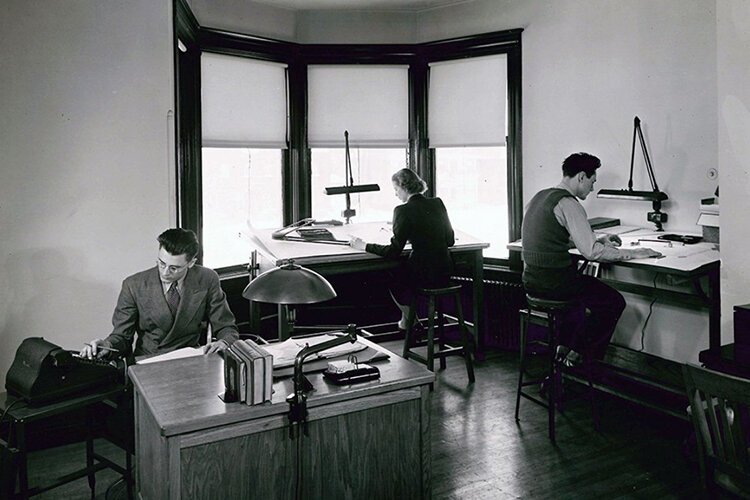

In 1947 the house became the headquarters for a national engineering company, American Society of Heating and Ventilating EngineersSOI occupied the house until 1946, when it became the headquarters for a national engineering company, American Society of Heating and Ventilating Engineers (today known as ASHRAE-American Society of Heating, Refrigerating and Air Conditioning Engineers). The Allen-Sullivan house and its auditorium served as a national research laboratory and offices for ASRAE until 1961.

In 1947 the house became the headquarters for a national engineering company, American Society of Heating and Ventilating EngineersSOI occupied the house until 1946, when it became the headquarters for a national engineering company, American Society of Heating and Ventilating Engineers (today known as ASHRAE-American Society of Heating, Refrigerating and Air Conditioning Engineers). The Allen-Sullivan house and its auditorium served as a national research laboratory and offices for ASRAE until 1961.

After this interval the house donned its final hat—serving as the Coliseum (or Colosseum) Party Center from 1964 to the late 1990s.

Mary and Benjamin Fisco, who restored the house to the condition of when it existed as the SOI Grand Lodge. The Fiscos ran the night club and party center until Benjamin Fisco’s death in the late 1990s. The house had fallen into disrepair and was neglected—foreshadowing its death at the hands of developers.

Signet Real Estate Group attempted to save the structure by working with the Cleveland Restoration Society and the Cleveland Landmarks Commission to find a buyer for the abandoned property.

Land on the other side of Euclid Avenue was set aside by the City of Cleveland and offered the plot for the relocation of the Allen-Sullivan house. But the developer didn’t want to take on the expensive task of restoring and relocating the property.

The Allen-Sullivan house in 2020 before demolition in 2021In 2021 Ken Prendergast, a writer for the NEOtrans blog, reported on the last efforts made to save the Allen-Sullivan House from demolition. Before its demise, the house and auditorium were documented by architectural historian Lauren Pacini and photographer Glenn Petranek.

The Allen-Sullivan house in 2020 before demolition in 2021In 2021 Ken Prendergast, a writer for the NEOtrans blog, reported on the last efforts made to save the Allen-Sullivan House from demolition. Before its demise, the house and auditorium were documented by architectural historian Lauren Pacini and photographer Glenn Petranek.

Although efforts to save the house ultimately failed, a number of architectural artifacts from the Allen-Sullivan house remain. Those artifacts will soonbe incorporated into common areas within MidTown’s Foundry Lofts, which now sits on the same property.

The artifacts will help to preserve the story of Euclid Avenue, which has transitioned from gritty thoroughfare to Millionaires' Row, back again to a gritty thoroughfare, to today’s resurgence as a stretch of comfortable middle-class housing developments.

Who can say what the next century holds?