Black Environmental Leaders and Global Shapers collaborate to fight environmental injustices

The concept of environmental justice is that all people, regardless of race, ethnicity or national origin, have the right to live, work, and recreate in a clean and safe environment.

But historically, that hasn’t been the case. Too many citizens, particularly in Cleveland, live in neighborhoods where environmental factors lead to health problems, poor quality of life, pr even lack of basic resources.

According to The Cleveland Comprehensive Environmental Policy Platform: a vision for 2021-2025, systemic racism embedded within state and federal policies from the past—like slavery, Jim Crow laws and redlining—perpetuate the environmental issues associated with environmental injustices, and similarly, state and federal policies, going forward, are needed to solve these problems.

Kwame Botchway & Global Shapers Curators from from North America & CarribeansTwo organizations, The Black Environmental Leaders Association (BEL) and the Global Shapers Cleveland Hub, have partnered to advance environmental justice in some very intentional and unique ways.

Kwame Botchway & Global Shapers Curators from from North America & CarribeansTwo organizations, The Black Environmental Leaders Association (BEL) and the Global Shapers Cleveland Hub, have partnered to advance environmental justice in some very intentional and unique ways.

Local environmentalists began talking as early as 2016 before formally establishing BEL in November 2020—aligning themselves as stewards of the natural and built environment to collaborate and raise awareness and advocate for environmental and economic justice.

The Global Shapers Community is an international network of young people driving dialogue, action, and change as part of an initiative of the World Economic Forum. Within The Global Shapers Community network, there are over 300 city-based hubs across the globe.

The hubs, each led by a curator (similar to president), consist of a diverse group of young people united by common values: inclusion, collaboration, and shared decision-making. Together, they create projects and change for their communities.

The BEL method

The BEL method

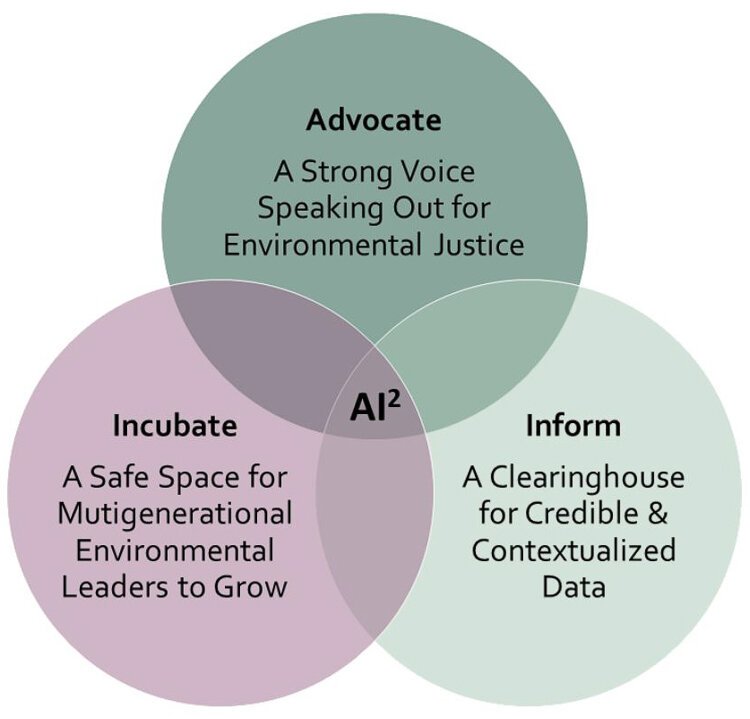

BEL’s strategy is to Advocate, Incubate and Inform, or A12. The late Jacqueline E. Gillon (in memoriam), David Wilson, SeMia Bray lead the organization in unison as co-facilitators.

“We utilize the distributed leadership model, which focuses on who is best to lead based on what we’re doing at the time,” says Bray, who explains that this approach avoids putting the burden on one person.

The group adopted this model, says Bray, because Gillon—considered one of the founders of Cleveland’s current environmental advocacy movement—believed everybody is a leader, bringing a level of expertise and agency to the table.

“We were very intentional about creating a circle of leaders,” says Bray.

BEL also implemented the concept of “head, heart, hands,” which speaks to how respective leadership styles complement each other for exponential growth. “Head, heart, hands” symbolizes the unique skill set each co-facilitator brings to the organization.

SeMia BrayBray represents the head and Wilson represents the hands. “It really sunk in when Jacquie passed away that she was the heartbeat of the organization,” recalls Bray. “She had a way of sharing her heart to where so many people considered her to be their best friend.”

SeMia BrayBray represents the head and Wilson represents the hands. “It really sunk in when Jacquie passed away that she was the heartbeat of the organization,” recalls Bray. “She had a way of sharing her heart to where so many people considered her to be their best friend.”

GIllon saw the humanity in everyone, Wilson adds. “She brought people into conversation. They came because of the topic and stayed because of the humanity.”

If Gillon saw something that needed to be changed, she wasn’t afraid to stand up and make her voice heard, says Wilson, and she unapologetically expressed her passion for improving the environment.

Environmental issues—such as poor air and water quality, lack of access to quality green space— especially in urban communities—toxic soil, climate change, food insecurity, transportation, and infrastructure, as well as lead in paint and pipes—are causing adverse health outcomes among the people who live where these problems persist and these issues are destroying the planet.

Some poor health outcomes as result of exposure to environmental problems or lack thereof include anemia, weakness, kidney and brain damage, chronic disease, and infant mortality. In Cleveland, the top environmental justice issues are lead exposure, lack of quality green space and a shrinking tree canopy, energy and water, air quality, infrastructure, and transportation and equity.

“People are still having adverse health issues because of decisions made 50, 60 years ago,” says Bray. “Take redlining—the impact is still felt.”

Dave WilsonFor example, due to redlining, you have food deserts in many urban communities which lead to obesity, diabetes and other weight-related concerns because the only food option is often junk food. That’s an injustice. Another injustice resulting from redlining is lack of green space in disinvested neighborhoods.

Dave WilsonFor example, due to redlining, you have food deserts in many urban communities which lead to obesity, diabetes and other weight-related concerns because the only food option is often junk food. That’s an injustice. Another injustice resulting from redlining is lack of green space in disinvested neighborhoods.

Bray explains that having adequate green space in a community has many benefits, including fresher, cleaner air and better soil.

Wilson says access to parks has psychological and mental developmental benefits as well. “It reduces stress and is proven that healthy child development occurs when they have access to green space.”

Additionally, Wilson says people coming together in public spaces helps foster greater social cohesion, connections, and improves the overall wellbeing of communities.

At BEL, different people are working on different issues simultaneously. In honor of Africa’s tribal traditions and vibrant cultures, BEL has five tribes based on environmental solutions areas, two affinity groups, and one overarching area to which all members contribute to and learn from, to facilitate collaborative decision making.

This shared leadership model enables the members to maximize all of the human resources within the organization by empowering individuals and giving them an opportunity to take leadership positions in their respective environmental solution areas of expertise.

“[It] allows us to get more done,” says Bray.

Some of the environmental issues BEL is currently addressing are the built environment, energy waste reduction, green building and healthy homes, healthy neighborhoods, land, air, and water to name just a few. Most importantly, BEL develops standards to inform policy.

Additionally, BEL co-facilitators genuinely believe young people have a lot of agency and perspective, yet are often disregarded and not heard.

So, from the early days, BEL’s co-facilitators knew they needed to take an intergenerational approach to address environmental issues by creating a seat at the table for younger voices.

“These are generational issues that require generational solutions,” says Wilson.

Bray adds, “So, we’re saying young people are not the leaders of tomorrow. They are the leaders of today.”

Today’s leaders

The Cleveland Hub of Global Shapers Community formed in 2011, shortly after the establishment of the international network. The only chapter in Ohio, it has 26 members between ages 18 and 29 years old. The goal is to leverage the passion of the group to create local change through a global lens by sparking critical conversations, prototyping design solutions, supporting community partners through project sprints, and approaching problems through the lens of human-centered design.

Kwame BotchwayKwame Botchway, a native of Accra, Ghana who currently works as director of impact and innovation at the nonprofit Cleveland Neighborhood Progress, is the curator of The Global Shapers’ Cleveland Hub.

Kwame BotchwayKwame Botchway, a native of Accra, Ghana who currently works as director of impact and innovation at the nonprofit Cleveland Neighborhood Progress, is the curator of The Global Shapers’ Cleveland Hub.

Botchway the group hosts two retreats each year to select issues members are passionate about, decide what projects members will work on in the community together, and tie these issues to the broader Sustainable Development Goals (SDG’s) of the global network.

“The Cleveland Hub has been doubling down on the environment over the last few years,” says Botchway. “So, we decided to host a Northeast Ohio Youth Climate Future Forum.”

The Cleveland Hub reached out to BEL in 2019 to co-sponsor the October 2020 forum, and Gillon played a major role in pulling the panel together, explains Botchway. Gillon also offered to have BEL act as the hub’s fiscal sponsor.

“This collaboration [with Global Shapers] is an attempt to push back and show what an intergenerational model could look like,” says Wilson.

Bray says Global Shapers checked all the boxes for what BEL looks for in youth partners.

“Black Environmental Leaders Association is sent from heaven,” says Botchway. “They have been incredible partners. My fondest memory of Jacqueline Gillon is her warmth and big smile. Even through her illness, she always checked in. We are inspired by her work and will be carrying that torch forward.”

Elena StachewElena Stachew, a Cleveland native and Ph.D candidate studying biomimicry at the University of Akron with a focus on coastal erosion, has been a member of Global Shapers’ Cleveland Hub since Sept. 2017. She has served as vice curator and project lead.

Elena StachewElena Stachew, a Cleveland native and Ph.D candidate studying biomimicry at the University of Akron with a focus on coastal erosion, has been a member of Global Shapers’ Cleveland Hub since Sept. 2017. She has served as vice curator and project lead.

As a more senior member, Stachew is the “climate action guru” who helps get a lot of the climate projects off the ground. She represented Cleveland at the 2019 U.N. Youth Climate Summit.

Stachew, who initiated the relationship with BEL, says she considers the members to be true partners, mentors, and friends—adding the group has been accessible, transparent, friendly, and welcoming.

“It’s been absolutely amazing,” Stachew says. “I love working with SeMia, David, and Jacquie, when she was with us. She just warmed everyone’s heart.”

As a result of the NEO Youth Climate Future Forum, Global Shapers established the Northeast Ohio Youth Climate Action Fund which issues small grants up to $2,500 for local teenagers with project ideas addressing the environment.

Global Shapers also plans to host “Listen, Lead, Share” community conversations on environmental justice as it pertains to Northeast Ohio, through the support of the Ohio Climate Justice Fund. The group also works with BEL to inform broader community awareness of best practices regarding equity, jobs, and justice in Ohio.

Global Shapers are always actively recruiting new members and encouraging young people to build long-term careers in any industryin Cleveland by offering support and professional development.

“We help our members gain leadership experience and broaden their skills in ways they may not get a chance to on their day jobs,” says Stachew.

Knowing environmental justice issues are all interconnected, that they need a holistic approach and are going to be even more aggravated in the future, Botchway says, “The goal is to work together, collectively, to address the issues in a more comprehensive way.”

Stachew says what frustrates her the most is how sustainability became its own entity and isn’t embedded in every discipline.

“I wish no matter what major [in college] you are in, that you are required to take a sustainability or ecology class to connect to your local place, [to] understand the geography, the geology, the natural history, and to even be able to identify some local plants and trees,” says Stachew.

Stachew explains that this knowledge can inspire people to call a place like Cleveland their “home” and be embedded within their communities to make our region a more livable, happier, and equitable place for all.

The late Jacqueline E. Gillon—considered one of the founders of Cleveland’s current environmental advocacy movement, is one of BEL’s co-facilitators.The legacy of Jacqueline E. Gillon

The late Jacqueline E. Gillon—considered one of the founders of Cleveland’s current environmental advocacy movement, is one of BEL’s co-facilitators.The legacy of Jacqueline E. Gillon

Gillon died of cancer at age 65 last August 24. Prior to her passing, in addition to her commitment to BEL, she worked at the Western Reserve Land Conservancy. Her contributions in the environmental justice space are well-known and respected not only across Cleveland, but throughout the country.

Gillon’s younger brother Sidney Gillon explains that their dad was active in politics. That interest spilled over to his sister, who became the youngest East Cleveland city commissioner, right out of college and served as a member of East Cleveland City Council.

“For her, it was the impact, what you can do for your neighbor,” Sidney Gillon says. He recalls “The Renaissance for East Cleveland” at Pattison Park, as one of her early land use projects and her enthusiasm for the passage of the Clean Water Act in 1972 — the first environmental legislation ever enacted.

“That was a big motivator for her,” Sidney Gillon recalls. “Things that motivated others didn’t motivate her.”

Mark McClain, Gillon’s oldest friend, says she was a longtime community advocate, which sparked her interest in environmental issues. “Environment is paramount to community work,” says McClain. “It touches the community.”

McClain says this work became important to Gillon because she was a people person and you can’t be a people person without concern for the collective. “When you take a holistic approach, you have to look at the conditions in which people live.”

McClain says Gillon also tried to help people make the connection between environmental issues and poor health outcomes and that she looked at environmental issuesfrom a spiritual lens. She believed God created the environment and we are destroying it.

“She always talked about the lack of buy-in, the fact that we didn’t pay attention and tried to connect those dots for the average ‘Joe;’” says Sidney.

McClain hopes Gillon’s efforts were not in vain. “We have to continue the fight,” he says.

Elise Thompkins, Gillon’s roommate at Hiram College, says one thing she learned from Gillon is that the environment impacts our overall wellbeing, “It all came together, she tied her whole life’s work together,” Thompkins.

“Food insecurities, infant mortality, asthma—it all ties back to the environment.”

Thompkins says one of Gillon’s pet peeves was how the majority community thought Black people didn’t care about the environment. Gillon knew otherwise. She traveled to other cities and met other minorities with interests and passions in addressing environmental injustices. She also says Jacquie really appreciated young people.

“She wanted to do everything she could to inspire and support [them],” says Thompkins.

“Jacquie spent a lot of time making sure the generation who are becoming adults now has a firm understanding of where they’re at and how they got to where they are at. It’s not just random. There was work done,” says Sidney.

Garden of 11 Angels on Imperial Avenue in Cleveland’s Mount Pleasant neighborhood.Anyone who knew Gillon knew that adequate greenspace and land use, especially the repurposing and reimagining of vacant lots, were her passion. It was Gillon who, early on after the discovery of the Anthony Sowell murders, advocated for the Garden of 11 Angels on Imperial Avenue in Cleveland’s Mount Pleasant neighborhood. Gillon even played a major role in influencing its design but passed away before its November dedication.

Garden of 11 Angels on Imperial Avenue in Cleveland’s Mount Pleasant neighborhood.Anyone who knew Gillon knew that adequate greenspace and land use, especially the repurposing and reimagining of vacant lots, were her passion. It was Gillon who, early on after the discovery of the Anthony Sowell murders, advocated for the Garden of 11 Angels on Imperial Avenue in Cleveland’s Mount Pleasant neighborhood. Gillon even played a major role in influencing its design but passed away before its November dedication.

“Jacquie had a vision to see that land used in that way,” says Bray. “Her vision was to create a park where people can come together and gather to memorialize victims and survivors and be used for communal and collaborative purposes.”

And in true Jacquie fashion, Sidney says, she requested to be cremated and planted with a tree on the grounds of her beloved Elizabeth Baptist Church.

One thing about Gillon people may not know, notes her sister Sharon Simmons, is Jacquie’s musical talents and how much she loved to dance. “She was a gifted violinist. She played all through elementary and junior. high and was a part of the all-city orchestra.”

This story is the first of a ten-part series of articles designed to highlight how this intergenerational model is helpful in moving the needle in so many aspects of Cleveland as well as to uplift narratives of resilience and impact within the environmental justice space. Upcoming stories will spotlight different organizations working on environmental justice and climate change as well as capture the intergenerational voices working on these issues.