Original grassroots: How Buckeye Woodland activists agitated for affordable utilities in the 1970s

Over the decades thousands of people have faced soaring gas, light, and water bills. In recent months the government started to end COVID-19 utility bill moratoriums, forcing low-income residents to wade through a maze of assistance programs.

It turns out that the struggle to keep the lights on is an old one. More than 40 years ago, the Buckeye Woodland Community Congress (BWCC) shut down the East Ohio Gas building, crashed an energy company board meeting, and disrupted a fancy lunch in Gate Mills to get the corporate executives of major utility companies to reduce heating costs for seniors and get accurate meters for resident’s homes.

Some of their efforts resulted in victories. Others in defeat. However, it seems that even when they were defeated the compromise yielded great benefits and the organizers achieved their goals.

Some of their efforts resulted in victories. Others in defeat. However, it seems that even when they were defeated the compromise yielded great benefits and the organizers achieved their goals.

The BWCC was the brainchild of the Catholic Diocese of Cleveland as an effort to bring together the ethnically diverse and divided Hungarian, Italian, and Black residents that comprised the Buckeye and Woodland neighborhoods.

Many white families had moved from Buckeye Woodland, and those that remained were at odds with the influx of Black people coming from the South. The goal of the BWCC was to work toward obtaining everyday needs—like housing, reasonable utility costs, ending redlining, and other actions that were harmful to the local communities.

The BWCC held its inaugural meeting on February 15, 1975, at Benedictine High School in Woodland Hills.

In a May Zoom meeting, NEO SoJo writer Sharon Lewis spoke with George Barany, a BWCC organizer who was hired just two weeks after graduating from Case Western Reserve University in 1976.

The BWCC was looking for a Hungarian-speaking community organizer because of the heavy concentration of Hungarian residents in the Buckeye Woodland neighborhoods. Barany—a first-generation Hungarian American who resided in the neighborhood and had experience in political campaigns—fit the bill.

George BaranyBarany, 67, worked for BWCC for a little more than three years. Today, he lives in today in Cleveland Heights and is the executive director of America Saves.

George BaranyBarany, 67, worked for BWCC for a little more than three years. Today, he lives in today in Cleveland Heights and is the executive director of America Saves.

Lewis in April also interviewed Randy Cunningham, author of “Democratizing Cleveland: The Rise and Fall of Community Organizing in Cleveland, Ohio 1975-1985.” While not a member of the BWCC, he worked at the Near West Housing Corporation—a spinoff housing organization of the community activist group Near West Neighbors in Action.

Cunningham, also 71 and a resident of Cleveland, was present at several of the “actions” or “hits” undertaken by the BWCC and the coalition of community organizations against target corporations like East Ohio Gas and SOHIO. He worked in housing for 30 years.

Lewis spoke with both Barany and Cunningham to travel the backroads of the early days of community organizing in Cleveland. Here is that conversation:

Sharon Lewis (SL): Can you both describe the BWCC from your perspective?

George Barany (GB): The BWCC was one of the first of its kind in the country. Its purpose was to promote racial harmony and generate power for underserved and impoverished communities. BWCC used [community activist] Saul Alinsky-style strategies and tactics. The Catholic church supported the organization via the Campaign for Human Development and nationally by the National Conference of Bishops, its initial funder. BWCC was an experiment by the Catholic Diocese of Cleveland to generate social justice in a community ravished by a slew of issues, from panic peddling by realtors and redlining by banks and insurance companies and disinvestment on the part of the city and state.

Randy Cunningham (RC): The Buckeye Woodland Community Congress was an attempt to successfully organize in one of Cleveland's most racially conflicted neighborhoods at the time. It was an experiment of the Commission for Catholic Community Action to bring together the ethnics (Italian, Hungarian) of the neighborhood with the rising Black community moving into the area on issues of mutual concern.

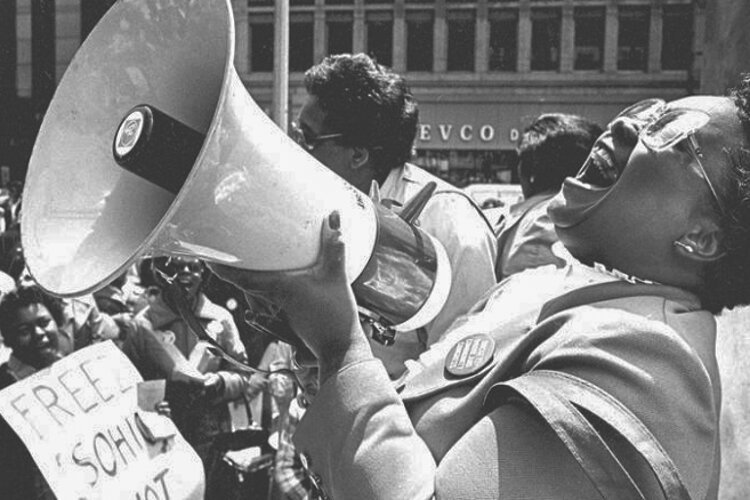

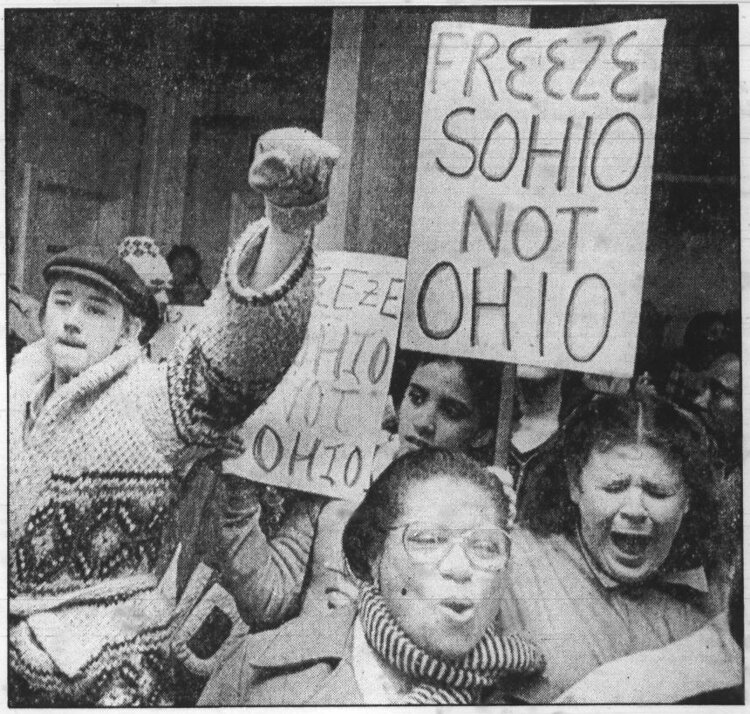

“No way, we won’t pay” Buckeye Woodland Community Congress’ protesters chant at Stouffer’s Inn on the Square outside Sohio’s annual meeting.

“No way, we won’t pay” Buckeye Woodland Community Congress’ protesters chant at Stouffer’s Inn on the Square outside Sohio’s annual meeting.

A first of its kind

SL: American community activist and political theorist, Saul Alinsky’s work was pivotal to the success of the BWCC and other community activist organizations then and now. His work through the Chicago-based Industrial Areas Foundation helping poor communities organize to press demands upon landlords, politicians, and business leaders won him national recognition and notoriety. For some, his tactics crossed the line of civility. For example, CEOs, politicians, and businesspeople were pursued both professionally and personally. It was commonplace to protest at someone's home, church, or social gathering.

From what I read, BWCC was an umbrella organization because it was the strongest of the community organizations. Was that the case?

GB: I would not describe the BWCC as a coalition. I would describe it as a community organization with a defined geography. Since it was the first of its kind, it took on the persona of being the biggest and baddest. We relished that reputation that we were just badass and tough and tougher than anybody else.

That reputation probably started because there were these neighborhood conferences—convenings where all the neighborhood organizations came together. BWCC always outproduced everyone in terms of the number of attendees. They had more people and more leaders upfront. Sometimes these meetings got crazy. I remember one where Fanny Lewis just went nuts on stage and threw a chair.

SL: So, with these meetings, if you brought the most people, you appeared to be the most powerful?

GB: Correct. I think that influenced the overall plan. We probably had more leaders engaged.

SL: Tom Gannon was the first lead organizer for the BWCC. What kind of person was Gannon?

GB: Tom Gannon was a good guy. I learned a lot from him and spent a good bit of time with him. We lived near each other. We used to go running a lot. He is the one who brought the swashbuckling, heavy drinking attitude to BWCC. If you were going to be a community organizer, you must be this “badass” kind of guy. I am not sure that that served us all that well. But that is the persona that we all sort of took. I think he liked being at the Diocese more than being at BWCC.

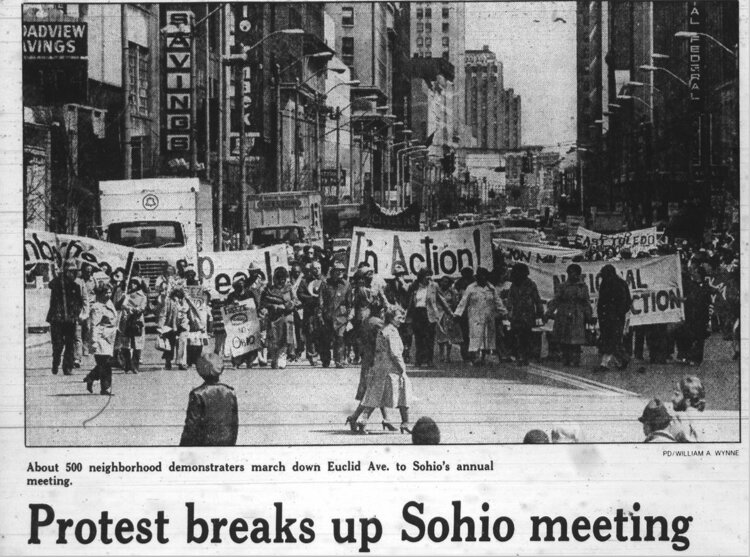

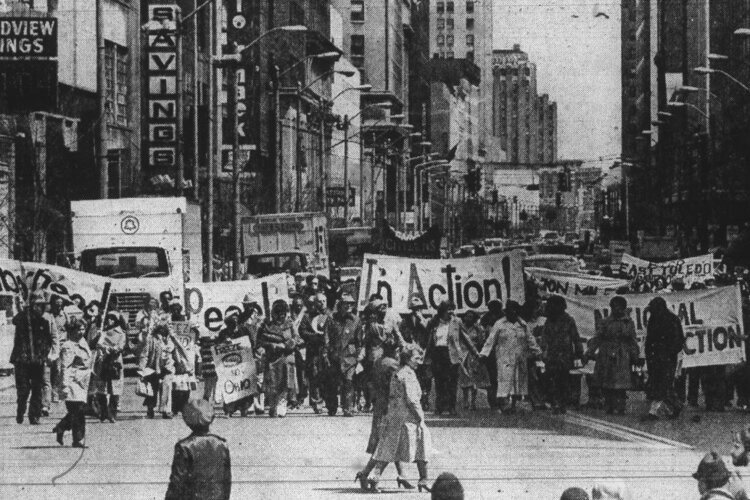

About 500 neighborhood demonstrators march down Euclid Ave. to Sohio’s annual meeting.SL: I want to focus on the energy campaigns undertaken by the BWCC and the coalition of community organizations in Cleveland from 1975 to 1985. The initial campaign was against East Ohio Gas (EOG), followed by SOHIO (Standard Oil of Ohio, currently named BP). How did the energy campaigns personally impact you?

About 500 neighborhood demonstrators march down Euclid Ave. to Sohio’s annual meeting.SL: I want to focus on the energy campaigns undertaken by the BWCC and the coalition of community organizations in Cleveland from 1975 to 1985. The initial campaign was against East Ohio Gas (EOG), followed by SOHIO (Standard Oil of Ohio, currently named BP). How did the energy campaigns personally impact you?

GB: The energy campaigns moved me out of community organizing for all intents and purposes. I became the focal point for the “powers that be” as if I were the sole determiner of policies and actions so, George got his funding cut. I then went to work in Lorain County organizing seniors for about a year and a half. I remade myself and returned to Cleveland as the Director of the Senior Citizens Coalition.

Campaigning for change

SL: What can you tell me about your recollections of the energy campaigns? Start with East Ohio Gas.

GB: We took over the East Ohio Gas building several times. Keep in mind that no one organization was responsible for an "action." The Senior Citizens Coalition offices were at the Catholic Diocese in downtown Cleveland. We were just doors from the East Ohio Gas Building. So, we would gather at the Diocese and march the half block to their building on the days we planned to take over the East Ohio Gas Building. They would usually shut down the facility and not let us in, which means they did not let anybody enter. Even if we did not get in, we shut down the building.

An interesting tactic that we used in the fight against EOG was to get a couple of hundred seniors to pay their gas bills in pennies at National City Bank. We did that because the CEO of National City Bank was on the board of EOG. That held up the lines in the bank for quite a while.

On one occasion, when we shut down EOG, I had a staff member who was quite tall dressed up as a chicken because the CEO of EOG was too chicken to meet with senior citizens.

On another occasion, they were waiting for us. EOG tried to block the road. They had people with video cameras recording us. Also, the public relations person at EOG, Pitt Curtis, was trying to tell city leaders that I was a communist and an outside agitator and that they should not be listening to me. I believe they generated an FBI file on me.

SL: What was the goal of the campaign against East Ohio Gas (EOG)?

GB: The goal was to reduce heating costs for seniors and get gas meters placed on the outside of everyone’s home because everyone was getting electronically generated bills that were not real or reflective of their actual usage.

We did end up winning that. We got free meters for seniors throughout Cuyahoga County. That was mostly a senior effort going after EOG.

RC: The East Ohio campaign resulted in intangible accomplishments. East Ohio ceased winter shut offs and, under pressure from PUCO (Public Utilities Commission of Ohio), finally cooperated with the demand to support home insulation programs.

East Ohio funded an energy audit program. The program generated applicants for a wide range of home insulation programs that increased through the early 1980s. As with many organizing victories, these programs became a stable funding generator for the non-profit development groups.

Taking on Pig Oil

SL: Now, let us turn to some of the "actions" against SOHIO and the goal of that campaign. In an article shared with me by Toni Johnson, who previously worked for the Senior Citizens Coalition, SOHIO was called Pig Oil during this campaign. Do you recall who came up with that name?

GB: I do not remember. Before an "action," the organizers would get together, and we would think up what we wanted to do. We would walk through the whole event. We would make up songs and activities. So, I am sure that somebody around the table came up with the idea.

RC: The switch in focus to SOHIO began in early 1981. Taking the lead was Neighborhood People in Action (NPIA).

Organizations working on the issue were: Near West Neighbors in Action (NWNIA), BWCC, Senior Citizens Coalition (SCC), St. Clair Citizens Coalition (SCSC), Union Miles Community Coalition (UMCC), and Citizens to Bring Back Broadway (CBBB). The campaign's first goal was to garner as much support as possible from local, state, and national politicians and representatives to fight the Reagan administration’s plan to deregulate natural gas prices.

The second goal was to secure from SOHIO $1 billion to finance energy conservation and subsidy programs for low and moderate-income utility customers.

The group confronted an industry around an issue considered a top priority by the industry and would move heaven and earth to win. NPA groups could harass SOHIO's CEO Alton Whitehouse all they wanted. Still, Whitehouse would not go against a national policy proposal that would earn his company billions of dollars in profits. He would ignore them if he could. When he could not ignore the groups anymore, he would make phone calls to their funders. Either way, they would lose.

SL: What can you tell me about the action that shut down SOHIO’s stockholder’s meeting?

GB: We had several public meetings inviting SOHIO out when deregulation of natural gas prices was causing gas to go up. Each time they sent out their Public Relations person, Pitt Curtiss. We did not get any answers. So, that is when we finally went to the building to make that demand and continued asking to meet with someone with absolute authority. We did this repeatedly.

RC: The focus of the spring activities for NPIA was the upcoming demonstration at the April 22, 1982, stockholders meeting of SOHIO held at Stouffer's Hotel (now the Renaissance Hotel) on Cleveland's public square. There was a two-part action plan. First, the NPIA group had collected about 100 proxy votes from sympathetic institutions and individuals so that their representatives could be present at the stockholders' meeting. The second part was a demonstration and picket line outside of the hotel to protest the corporate policies of SOHI0 and gain public attention for NPIAs energy campaign.

SOHIO had anticipated this move in the aftermath of the Chicago Shoot Out with Pig Oil demonstrations in November 1981. It began to monitor stock transactions to see whether any group was purchasing blocks of stock that could be used for proxies to gain entrance to the stockholders' meeting.

The plans NPIA had made for its activities that day did not hold up under the excitement and pressure of the moment. Security was all over the hotel but, by some fluke, the front entrance of Stouffer's had been left unguarded. Demonstrators outside the hotel, numbering in the hundreds, entered the hotel lobby. Neighborhood people blowing penny whistles and waving banners and placards occupied the lobby and filled the ornate stairway that led to the stockholders' meeting.

At the meeting, SOHIO management refused to recognize speakers representing NPIA. The NPIA contingent advanced on the stage where the officials were seated, and a confrontation ensued. Officers of the board abruptly declared the meeting adjourned. The shortest, most tumultuous stockholders meeting in SOHIO history was over.

Organizers of the demonstration thought that they had shut down the meeting themselves. However, SOHIO maintained that the abrupt ending had been a conscious decision made by the company beforehand.

SL: What was the result of this action for the organizers?

RC: SOHIO hit back at the groups in a media campaign that challenged the legitimacy of the protest.

GB: You see, all of the CEOs and corporate board members were connected professionally and socially. All they had to do was talk to one another to withdraw funding for your organization.

An enjoyable hunt

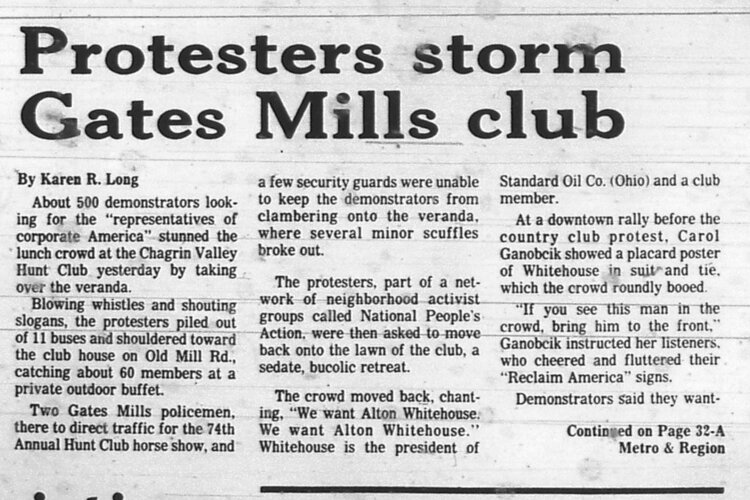

SL: There was an action at the Chagrin Valley Hunt Club? What happened, and who was the target?

GB: It was a lot of fun and exciting. It was great. Another organizer, Ken Esposito, and I scouted out the Hunt Club for a couple of weeks to make sure we knew which routes to take, to direct the busses, and how to leave. That day was one of their biggest days when they were out there hunting foxes. So, yeah, they did not like it. There were 11 busses, approximately 600 people that disembarked and demanded to see Alton Whitehouse, the CEO of SOHIO. They were chanting, "Freeze SOHIO, Not Ohio," and singing “Give us a Billion Dollars” to the tune of “Wade in the Water.”

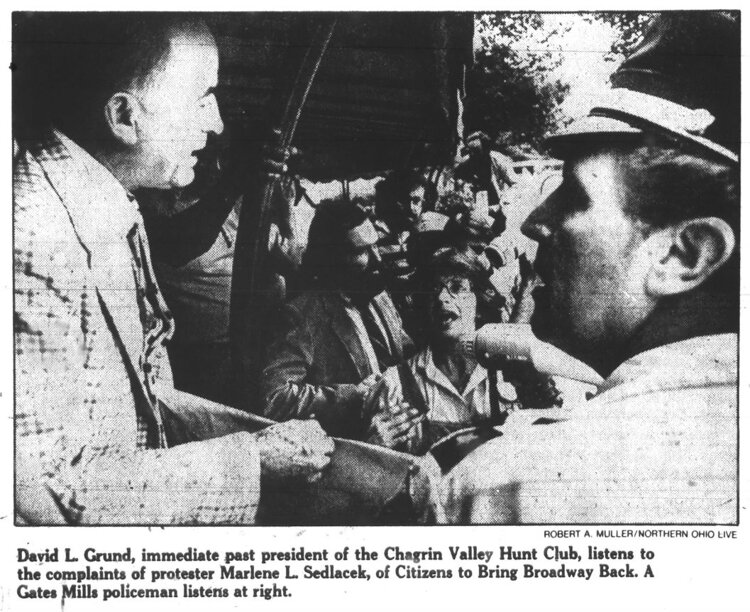

RC: What occurred when the 600 demonstrators landed at the Hunt Club was not just a political event. It was a collision of worlds that barely recognized each other’s existence and that never came into contact. That afternoon at the Hunt Club, the Club Chairman’s Saturday lunch was in progress. The veranda was full of well-dressed diners, and members in English riding outfits were tending their mounts, gathering for the afternoon’s equestrian events.

Pouring out of the buses were organizers in jeans. Working-class and poor people in polyester. The Hunt Club had never seen that many Blacks, those who were not among those the English call "the great and the good."

A confrontation soon developed between the management of the Hunt Club, the overwhelmed police force of the Village of Gates Mills, and the leadership of the demonstration. Those poor people just did not know what was going on. They were sitting there having lunch, totally decked out, with tablecloths and crystal. People were saying, 'Excuse me, I'm thirsty. Do you mind if I drink out of your water glass?' People did not know what to do.

The demonstrators demanded to see Whitehouse. Hunt Club management responded that he was not present that day. Shouting matches between enraged luncheon guests and individual demonstrators erupted. The wife of James Lipscomb of the Gund Foundation reportedly had one person from the caravan take her glass of wine, toast her, and down it.

Finally, the management of the club promised to give Whitehouse a message, and the demonstration ended. The caravan went on to its next stop, and the rest of the Cleveland contingent returned to face a reaction that made that of the stockholders’ meeting seem tame.

While many who attended this hit were thrilled at the confrontation, there was also an undercurrent of embarrassment.

GB: There was one sheriff that showed up. He threatened to arrest us all. We just laughed at him.

SL: What was BWCC's contribution to the neighborhoods of Cleveland and the surrounding area?

RC: First, BWCC provided the template on how to start a community organization. Secondly, they trained an initial cadre of organizers who left BWCC to start other community groups, to advise other groups, and to work as trainers of new batches of community organizers for the Commission on Catholic Community Action out of the Diocese of Cleveland.

Long-term results

SL: What was the overall effect of the energy campaigns on community activism in Cleveland?

RC: The energy organizing was the Waterloo of the groups. It looked like a good issue but brought them into conflict with where the real power is in Cleveland—corporate power as represented by the SOHIO (now BP) corporation. The campaign exposed all the vulnerabilities of the movement. SOHIO made the rounds of the foundations in Cleveland to complain about the groups, and then the foundations defunded them. The tensions of the campaign exposed tensions and fractures that existed within the movement. The campaign showed the weaknesses of the community organizing model. Energy organizing ended up being the perfect storm for the groups and led to their demise and the onset of a civic and activist ice age that is just now starting to melt.

GB: The funding for the organizations was already waning. The takeover of the Hunt Club and the SOHIO Annual Meeting simply put the nail in the coffin.

From the SOHIO Campaign, millions got funneled to the Community Development Corporations. So, the organizing generated new opportunities and stability for all the Community Development Corporations because it was their way out. It showed that they were still doing something good. They were just not dealing with the radicals in the community organizations.

SL: Do you think that the community organizations could have continued under the circumstances?

GB: I am not sure. However, the funders were content with the Community Development Corporations that activism had spawned. It was easier to quantify their impact more clearly because they could go and visit a rehabbed house versus an amorphous concept of getting the city to increase garbage pickup.

Organizing for current issues

SL: What type of activist organization does Cleveland need today?

RC: It needs an organization and organizations that can walk on both feet. It requires an organization that is equally proficient at street-level organizing and old-fashioned electoral work. It needs an organization that is not confined and muzzled by its funders – the foundations. There were two significant failings of the groups that BWCC launched. Because of 501c3 restrictions, they had to take a vow of political chastity. And the community organizing dogma of the day was utterly hostile to political work in the electoral field. They talked a good game about empowering communities but then refused to build power where power is deployed: Politics.

GB: We need to go back to our roots. We need door knocking. Walking through neighborhoods is a little scary because everybody has a gun, and everybody is quick to use them. But we do need to rebuild a sense of community. The only way I know how to do that is by convening people to realize mutual self-interest and focus on something they can work on together beyond Black, White, and Latino, and economics so that there is a sense that we are all in this together.

Cleveland continually frustrates. Cleveland needs significant investment and a sense of hope that I am just not seeing in many neighborhoods.

SL: What areas do we need to address in terms of community organizing? Is it still the same?

GB: I do not see energy as that big of an issue today. Many cases need to be examined today.

I think housing and homeownership are primary issues.

Wages. People should be making $15.00 an hour at least, so they do not have to work three jobs and continue to live in some sense of poverty.

Safety is still a big issue. I do not think that the police know how to police. So, that entity needs repair.

Education. Our graduation rates are still too low. I think we need more programmatic efforts. There must be a reason why children are not graduating or interested in school. We must figure out different ways to engage them and get them excited about learning. Why? Because that is their only hope for a positive future.

SL: Any parting thoughts?

RC: A concerted effort by SOHIO to get the groups defunded, and a change in the culture of the town and nation brought about by the Reagan administration, contributed to death by a thousand cuts for BWCC and the overall movement. BWCC closed shop in 1985 in a process that was at times both tragic and comedic. Most of the movement it founded had already collapsed by then. The ultimate lesson for BWCC and all community organizations and nonprofits is simple. Never trust or depend on the foundations. Most people look upon them as benevolent. I look upon them as being malevolent, the outer defensive perimeter of the status quo, and how the elite in our society pull our strings. Regarding American dissent, activism, and social movements, I sum it up this way. "Who needs the FBI when you have the foundations?"

GB: The history of community organizing demonstrates how difficult it was and still is to get a major corporation to look at the community where it is located and want to do something beyond the traditional, i.e., orchestra, theater, etc.

While we did not win directly, we won indirectly. The development corporations, many of which still exist today, resulted from the funding support generated at that time because of our actions.

I do not know if we made mistakes. We confronted power, and we did not have enough power directly. But we faced it as best we knew how and asked for actual negotiations and conversations.

Every organizer I encountered did the work because they cared. They cared about people and wanted to see justice. The work was hard, and the hours were incredibly long. At a young age, I learned to work 80 hours a week. I loved it, absolutely loved it. We thought we were fighting the good fight and did it for the right reasons.

This story is sponsored by the Northeast Ohio Solutions Journalism Collaborative, which is composed of 20-plus Northeast Ohio news outlets including FreshWater Cleveland. Sharon Lewis is a Cleveland-based writer who works with FreshWater Cleveland, The Cleveland Observer and other area news outlets.