'Damn Fine Dog': Genomic sequencing allows researchers to investigate Balto’s pedigree

Most Clevelanders know of Balto, the 1925 sled dog that was part of the team that delivered lifesaving medicine to Nome, Alaska, during an outbreak of diphtheria.

Even before the taxidermized mount of the most famous sled dog in history was put on display in 1933 at the Cleveland Museum of Natural History (CMNH), his story was known.

Some of us met the preserved Balto during school trips to the museum when we were kids, others more recently watched the 1995 animated movie or read to our kids about the canine’s courage.

In 1925, Balto lead a team of sled dogs on the last leg of a 674-mile brutal journey from Nenana to Nome, carrying musher Gunnar Kaasen and diphtheria antitoxin. The serum was being sent by relay of 20 dogsled teams because icebound Nome couldn’t be reached by airplane.

Chief Science Officer, Dr Gavin Svenson Children’s lives were on the line. Despite a blizzard, a close drowning, and the serum being temporarily lost in a snowbank, the dogs, with Balto leading the safest way on the last 53-mile trek, arrived in Nome after six days. Balto was a worldwide instant hero.

Chief Science Officer, Dr Gavin Svenson Children’s lives were on the line. Despite a blizzard, a close drowning, and the serum being temporarily lost in a snowbank, the dogs, with Balto leading the safest way on the last 53-mile trek, arrived in Nome after six days. Balto was a worldwide instant hero.

That part of the story we knew. But until just recently we really didn’t know who Balto was genetically. He is often called an “Alaskan sled dog,” bred for many specialized traits. But that classification has never been recognized by the American Kennel Club (AKC) as an independent breed (the AKC calls Balto “a jet-black husky” on its website).

Who was this dog, really? How did sled dogs 100 years ago compare to today’s breeds of mushing dogs? And why does the research matter?

CMNH has helped in unraveling the mystery of Balto using DNA sequencing and genomics.

“We had always been interested in sequencing Balto,” says CMNH chief science officer Gavin Svenson. “What dogs was he related to? But one of our limits was that Balto was really old and was preserved as a taxidermy specimen.”

Svenson explains that genetic researchers use fresh tissue, blood, or DNA samples from hair or skin cells to answer these questions. “When you have a taxidermy specimen that has been on display for almost 100 years, you have to think that there is not going to be adequate DNA of adequate quality,” he explains.

Svenson says DNA breaks down over time when exposed to temperature fluctuation, water damage and other factors. Also, older technology required longer segments of unbroken DNA for analysis. “Tech has caught up, and now you can overcome those challenges,” he says. “That was the case with Balto.”

Dr. Beth Shapiro In 2018, the museum was contacted by Heather Huson, Cornell University associate professor of animal science. Huson had a particular interest in how genetics shaped canine traits. She was a competitive dog sled racer for 25 years, so she couldn’t pass up the chance to study Balto. CMNH sent a skin sample taken from Balto and sent it to the University of California for DNA analysis for advanced sequencing capabilities.

Dr. Beth Shapiro In 2018, the museum was contacted by Heather Huson, Cornell University associate professor of animal science. Huson had a particular interest in how genetics shaped canine traits. She was a competitive dog sled racer for 25 years, so she couldn’t pass up the chance to study Balto. CMNH sent a skin sample taken from Balto and sent it to the University of California for DNA analysis for advanced sequencing capabilities.

In April, “Science,” published the results of Balto’s sequencing and related comparison information in “Comparative Genomics of Balto, a Famous Historic Dog, Captures Lost Diversity of 1920s Sled Dogs.”

Svenson says this was a unique opportunity to learn more about this heroic dog.

“To take a famous dog from about a 100 years ago, get its DNA, and have that contribute to our scientific knowledge, is not something most people thought was possible,” says Svenson. “It’s not an opportunity that comes up a lot of times. It includes information that predates a lot of specialization in dog breeding.”

Young Balto Surprising findings

Young Balto Surprising findings

According to the research, Balto’s ancestral lineage showed no grey wolf relationship, although many people had guessed it would.

Instead, Balto, who was 14 years old when he died, shared a common ancestry with Siberian huskies, Samoyed dogs, Greenland sled dogs, Alaskan malamutes and Asian canines.

Balto’s heritage was more genetically diverse than modern sled dogs and showed a lower potential for developing harmful genetic variants (Balto had no offspring).

Some researchers believe Balto’s information can lead to genetic studies related to developing the most sought-after traits in working dogs. That can include sight assistance dogs, hearing assistance dogs, herding dogs, and dogs that can detect drugs, bombs, and bodies canines.

“This is the quintessential natural history story,” says Svenson. You have an organism that is born and bred for specific tasks—in this case, speed, stamina and strength. This is artificial evolution—taking a species of animal and creating different breeds. The evolution happens right before our eyes in terms of characteristics.”

Add that scientific innovation to “a disease outbreak that requires the delivery of a scientifically developed serum to solve the problem,” plus a great dog story, and it’s no wonder people all over the world love Balto, argues Svenson.

“These dogs pulled a guy on a sled through horrendous conditions to achieve a goal they themselves didn’t understand,” he says.

The value of taxidermy

There are those who object to taxidermy in general or disagree with displaying mounts in museums. Svenson respects those opinions. But he says he believes taxidermy and other preservation forms are great teaching tools. The materials, he says, allow museums and other educational institutions around the world to share collections, which they might not have access to, for specific research.

For example, The Cleveland Museum of Natural History’s fossil collection of sharks and prehistoric fish (including a fossil of Dunkleosteus terrelli, affectionally known as Dunk and Ohio’s official state fossil fish) are among the best and most scarce of their kind and are requested by other researchers for study, according to Svenson. He says preserved pieces—whether plant or animal— help in understanding ecosystems, environmental changes and “where life came from in the first place.

“Balto is a great example of a specimen and future technologies that we don’t even know exist yet,” Svenson explains. “Remember, [Balto] was preserved before we understood DNA. We don’t know yet what else we will be able to unlock in the future and how that may impact humanity. That alone is justification for preservation and protecting authentic natural heritage.”

Balto is temporarily off display due to the museum’s $150 million renovation and expansion project. When he returns, Balto will be in the new 50,000-square-foot Visitors Hall, featuring signature specimens.

“Do I think this particular genetic study would have generated so much interest if a famous dog like Balto wouldn’t have been involved,” asks Svenson. “No. But I am glad the museum played a part. It’s really neat.”

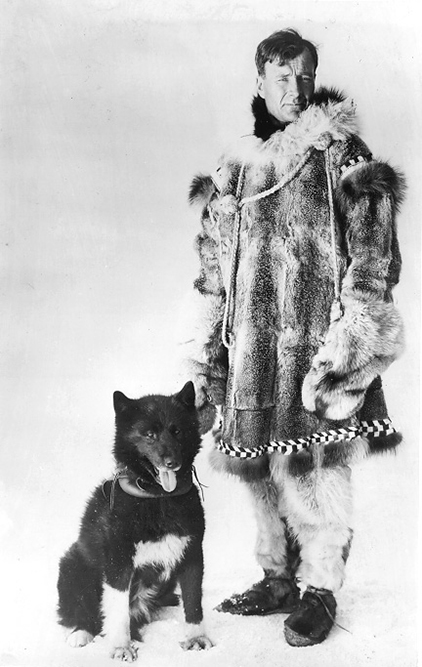

Balto with Gunnar Kaasen Balto’s story

Balto with Gunnar Kaasen Balto’s story

In 1925, Balto gained worldwide fame after leading a 13-dog team on the final leg of a 674-mile dogsled relay on what was dubbed Serum Run with 20 mushers and more than 150 dogs in a record 127 hours—an amazing feat of endurance despite -50°F temperatures and a raging blizzard

Musher Gunnar Kaasen went to Balto, hugging him and repeating the praise “Damn fine dog.”

After touring the United States vaudeville circuit with Kaasen for two years, Balto and his team were sold and put on display in a dime museum in Los Angeles. Ill and mistreated, Balto and six of his surviving teammates caught the attention of George Kimble, a businessman visiting from Cleveland.

Familiar with the story of the Serum Run and outraged by the deplorable conditions, Kimble arranged to purchase the dogs for $1,500. The only catch was that he had just two weeks to raise the money.

Kimble returned to Cleveland and established a Balto Fund, turning to national radio and local media to appeal for donations. The money was raised in just 10 days.

On March 19, 1927, Balto and his remaining teammates, Fox, Billy, Tillie, Sye, Old Moctoc, and Alaska Slim, received a hero’s welcome in Cleveland, complete with a parade through downtown’s Public Square. The sled dogs spent the rest of their days under the care of Cleveland’s Brookside Zoo, and Balto became a local Cleveland celebrity.

Following Balto’s natural death in 1933, his mount was put on display at the Museum.

Jill Sell is a longtime freelance writer, essayist and poet specializing in nature and the environment. (But writing is her obsession and few topics are off limits.) Her career includes being a community newspaper editor to contributor to international journals and everything in between. Sell lives in Sagamore Hills with an unkempt native wildflower patch and an unruly herb garden. She loves her dog, who is undeniably not as brave as Balto.