Biomimicry: nature meets industrial design at CIA

Douglas Paige, an associate professor in the Cleveland Institute of Art (CIA) industrial design department, enjoys pondering the trees in Wade Oval.

He compares an oak growing there in Cleveland’s temperate climate to a cactus growing in the desert climate of Arizona.

“It’s not that one is better than the other, it’s that each has adapted to its environment,” Paige explains, adding that grass and sprinklers in arid Arizona compete with the natural process. “It’s us trying to adapt to our own conditions, but we can’t compete with nature.”

That simple observation is one motivation for Paige adopting biomimicry – the art of finding practical solutions to design challenges by mimicking nature’s own solutions – into his industrial design teachings.

Examples include looking at the warming qualities of beaver fur to create a wetsuit or studying termite mounds to design a sustainable office building.

“Biomimicry is an emerging methodology, still being understood and defined,” Paige says. “Some debate whether it’s a discipline, a science, a tool or other. I see it as part of an overall methodology that every designer needs to understand moving forward.”

Douglas Paige, associate professor in the CIA industrial design dept

Douglas Paige, associate professor in the CIA industrial design dept

Paige views biomimicry as the next chapter of applying sustainable practices in design, or studying how nature solves problems to help meet industrial design challenges.

“Just as the computer revolution changed the way we work, and sustainability changed our focus and idea of responsibility, biomimicry is changing the way we view our role on this planet and how we think about problems and how to solve them,” Paige explains. “It's understanding nature and the planet as a resource for knowledge, not just raw materials.”

For example, Paige is working on a better boat paddle by studying fish, amphibians and waterfowl.

“Most people think of a paddle as moving through water, but a paddle blade is the piece that needs to stay in place while everything else moves,” he explains. “Using that, I looked for organisms that use drag-based locomotion - with little slip.”

The methodology emerged at CIA after co-founder of the Biomimicry Institute and author Janine Benyrus spoke on campus in 2007. Then in 2008, Dayna Baumsiter, co-founder and keystone of Biomimicry 3.8 led a biomimicry workshop at the school.

“The workshop helped us understand the process and how to incorporate it into design,” recalls Paige. “Biomimicry is changing the way we view our role on this planet and how we think about problems and to solve them."

He adds that biomimicry encourages designers to tackle challenges from all angles. “So many things apply the principles of how nature operates,” says Paige. “[It’s] understanding nature and the planet as a resource for knowledge - not just raw materials. The key is understanding the problem you are solving, and where to look in nature for examples of a similar functions.”

Paige and his students worked on the Green Bulkhead Project

Paige and his students worked on the Green Bulkhead Project

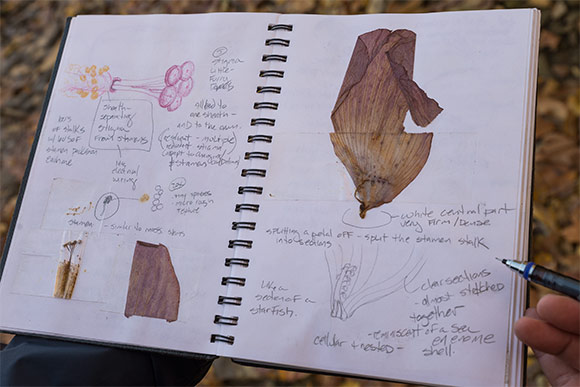

One of the first projects incorporating both sustainability and biomimicry into the curriculum began in 2009 when Paige and his students tackled water quality on the Cuyahoga River. They studied the rusty, failing bulkheads, why the river wasn’t healthy, the riparian zone (where land meets the water) and why larvae fish were dying.

“We found the steel bulkhead obliterates the main part of the river system – where the animals live – it slows down the flow, causes fast rises and releases,” Paige explains. “The bulkheads were built 100 years ago for industry. Now we have people, businesses, animals and industry. We needed to find a way to make everything survive.”

As part of the ongoing project, Paige and his students are looking at each individual system that makes up the river's biological community. “The biomimicry lesson is using an ecosystem approach,” he says. “We are studying how a natural river system works as an ecosystem and trying to incorporate some of those processes into a bulkhead system.”

The team has yet to define a workable solution, but continues to use biomimicry principals to explore ways to stabilize the river banks for the shipping industry and public use while also providing habitat for aquatic life.

For the pallet board challenge CIA students presented their designs and explain how it serves the needs of the modern classroom

For the pallet board challenge CIA students presented their designs and explain how it serves the needs of the modern classroom

“Further understanding the principles of how nature works '[Biomimicry 3.8] Life’s Principles’ helped to demonstrate how nature is inherently sustainable and helped inform design for sustainability,” says Paige, who was given a Water Quality Innovation Award in 2013 by Alliance for Water Future for his work with the Northeast Ohio Regional Sewer District.

Paige stresses the study of nature and it's practical applications are evolving. “Biomimicry is an emerging methodology, still being understood and defined,” he says. “Some argue whether it’s a discipline, a science, a tool or other. I see as part of an overall methodology that every designer needs to understand as we move forward.”

Teaching sustainable practices in his industrial design classes laid the foundation for this new chapter. For instance, in 2003 Paige and a group of industrial design students took on the challenge of transforming 1,500 pallet boards donated by G&M Pallet into furniture for Mound Elementary School in Cleveland.

“We spent a lot of time doing what I call ‘creating lumber,’” says Paige of the de-nailing and cleaning process. ”We found mahogany in there. It was so dirty and old we didn’t know until we cleaned it up.”

The students created furniture, including cubbies, a storage area, and a pin-up board. However, when the project was over, the group determined there just wasn’t a business model for recycling old pallets. “The best thing we learned was to take them to [landscape supply company] Kurtz Brothers for mulch,” says Paige - call that taking a cue from Mother Nature.

Mike Tracz, a 2004 CIA graduate, participated in the challenge by creating a modular desk. He says what he learned from Paige’s leadership in the task helped in developing his own innovative design company, Balance. The firm's diverse and impressive portfolio includes everything from vacuum cleaners to baby bottle brushes.

“He just gets his students thinking about the reusable,” Tracz says of Paige. “It’s a way of thinking and I incorporate it in my work at Balance.”

In working with those in the biomimicry field, Tracz says he sees the synergy between nature and industrial design. “We arrived at very unique solutions,” he observes. “We meet in the middle and come up with solutions you never would have thought of. It’s understanding each other’s language, it doesn’t have to be all or nothing," he says, adding, for instance that when designing a liquid soap dispenser using injection molding, it makes perfect sense to study the heart valve of an amoeba. “You meet in the middle,” he says. “It doesn’t have to be one way or the other.”

Paige agrees with Tracz’ philosophy. “We had been teaching sustainable design since about 2000 as a continually evolving process,” says Paige. “But biomimicry pushed it further. Now we incorporate biomimicry into sustainable design process as both an overarching principle and guidelines - as well as a design problem solving methodology.”

Paige, himself a 1982 CIA industrial design graduate, is a certified biomimicry professional by Biomimicry 3.8 and holds a master’s degree in biomimicry from Arizona State University. He grew up in Mentor and lives in Lakewood.

In his spare time, Paige enjoys kayaking and spending time in the Cleveland Metroparks Rocky River reservation and Wendy Park. He's also working on his startup company, Hedgemon, LLC, which is developing a new line of material for sports safety equipment, the design of which is informed by studying hedgehogs and their unique spines.

“In their environment, hedgehogs forage in trees for insects and their fastest escape from predators is to roll into a ball and fall,” explains Paige. “We’re look at nature to create different energy-absorbing padding and helmets. We’ve had some promising results already.”

The Cleveland Institute of Art is part of Fresh Water's underwriting support network.