Black Cleveland churches host vaccine clinics to protect their flock, and their communities

Cleosene Johnson has attended Affinity Missionary Baptist Church in Cleveland’s Lee-Miles neighborhood since 1976. And on a windy morning in late March, she went there to get her second dose of the COVID-19 vaccine.

Johnson, 72, had a hard time getting registered for a shot back in February, she said, when vaccines were scarce in Ohio and most other locations in the U.S. When she heard her church was offering the vaccine, she was excited.

“I said, ‘put my name on the list!” she says.

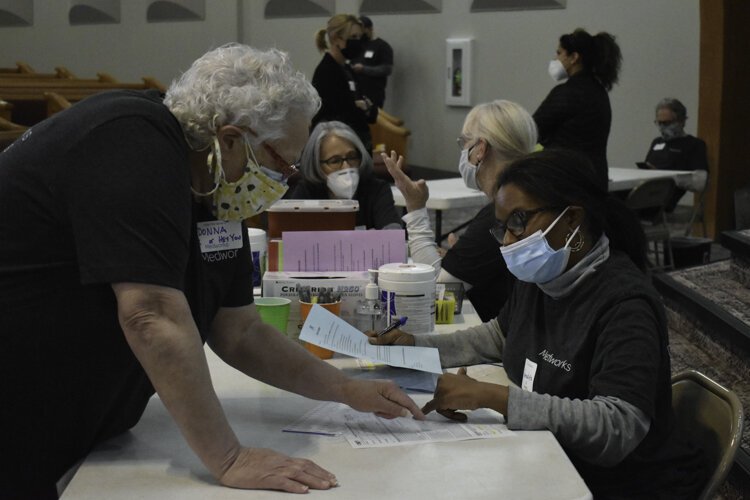

Several volunteers with Cleveland nonprofit Medworks prep vaccine doses at Affinity Missionary Baptist Church during a recent vaccine clinic.For Johnson, part of that joy was simply being back at church. Affinity’s pastor, Rev. Ronald Maxwell, said that for many, the vaccine clinic was their first time inside the church since the pandemic struck and the building was closed for renovation.

Several volunteers with Cleveland nonprofit Medworks prep vaccine doses at Affinity Missionary Baptist Church during a recent vaccine clinic.For Johnson, part of that joy was simply being back at church. Affinity’s pastor, Rev. Ronald Maxwell, said that for many, the vaccine clinic was their first time inside the church since the pandemic struck and the building was closed for renovation.

“One of the things Jesus got in trouble for was he’d always do healing on Sundays, which meant he was doing healing in the place of worship,” Maxwell said, noting how appropriate it felt to host vaccinations at his church.

Affinity Missionary, built in 1973, is one of multiple historically Black churches in Cleveland that have played host to regular vaccination sites since February, through an initiative started by the Greater Cleveland Congregations’ (GCC) interfaith coalition.

Keisha Krumm, executive director of GCC, says the vaccine clinics—through GCC’s Color of Health initiative—are trying to address a serious problem: Vaccinations for Black residents in Cuyahoga County have consistently lagged behind vaccinations for white residents. In the county:

- About 45% of all white residents have received a first dose of the vaccine as of April 19 (about 356,000 people).

- About 21% of all Black residents (about 80,500 people) have gotten their first dose, despite almost one third of Cuyahoga County being Black (about 376,000 people).

One caveat is that these population statistics do include those still ineligible for the vaccine, like young children.

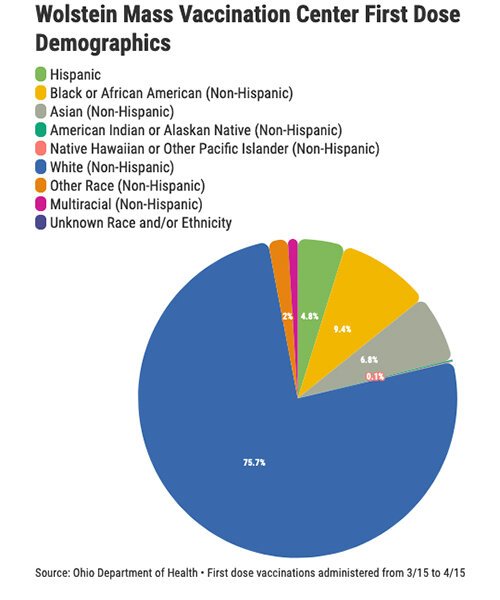

The Ohio Department of Health’s (ODH) mass vaccination site at Cleveland State University’s Wolstein Center is a prime example of that discrepancy. According to data provided by the ODH, as of April 5, less than 9.5% of all first shots administered at the Wolstein Center went to Black people (about 11,000 people), compared to 75% of all shots going to white people (about 91,000 people). Similar disparities are playing out nationally, as well.

The Ohio Department of Health’s (ODH) mass vaccination site at Cleveland State University’s Wolstein Center is a prime example of that discrepancy. According to data provided by the ODH, as of April 5, less than 9.5% of all first shots administered at the Wolstein Center went to Black people (about 11,000 people), compared to 75% of all shots going to white people (about 91,000 people). Similar disparities are playing out nationally, as well.

Still, ODH spokesperson Alicia Shoults says the state did well in delivering doses to vulnerable populations, with more than 46% of first doses at the Wolstein Center going to people living in zip codes with high Social Vulnerability Index ratings. These are neighborhoods with high poverty rates and low access to transportation and other amenities.

Meanwhile, the GCC vaccination sites have seen significant turnout for Black Cleveland and Cuyahoga County residents, with more than 90% of shots going to Black people at most of the clinics, Krumm says. The church with the lowest percentage still had more than 60% Black recipients. So far, about 2,700 people have received their first dose through the initiative.

Krumm attributes the high Black turnout rate to several factors.

“Our congregations have really done the work to get the word out to their members and their congregations, and to their friends and their networks,” she says. “It wasn’t just that we sent out a flier. We’ve been really intentional about calling people and having conversations.”

Krumm says that most of that communication was through phone and email.

Another big reason for the turnout? The churches are “trusted spaces,” plus they’re close to where people live, Maxwell explains.

“I think it’s a combination of one, locale, and two, trusted locations and that familiarity, just in your neighborhood and then three, targeted, just making sure you’re using lines of communication that reach certain populations,” Maxwell continues.

There’s not much consensus yet on why the racial disparity in vaccinations has persisted. One recent Pew Research Center poll suggested that as more information has come out about COVID-19 vaccines, Black Americans have become more likely to want the vaccine—up to 61% recently from 42% in November (69% of those surveyed overall in that poll said they wanted to get vaccinated).

Krumm says GCC has seen a similar growth in confidence, with those getting vaccinated spreading the word to others.

“The people that we’ve got vaccinated, they’ve become part of the recruitment mechanism to get their friends and family scheduled,” she says.

But she cautioned that it’s not just about hesitancy. There are still serious barriers for people to access the vaccine, whether it be a lack of access to transportation, lack of access to the Internet (most vaccination sites are requiring people to sign up online), or the inability to get time off work.

“Even if you wanted to do it, if you work two jobs, and you’ve got six kids, how do you make that happen?” she says.

Rev. Ronald Maxwell, pastor of Affinity Missionary Baptist Church, and Keisha Krumm, executive director of Greater Cleveland Congregations during a recent vaccine clinic.

Rev. Ronald Maxwell, pastor of Affinity Missionary Baptist Church, and Keisha Krumm, executive director of Greater Cleveland Congregations during a recent vaccine clinic.

“By going to church, people feel safe”

Terrie Williams, a resident of Cleveland’s Lee-Harvard neighborhood, sat in the pews of Affinity Missionary Baptist Church on a recent Thursday morning, resting for the mandated 15 minutes after her second dose of the vaccine.

For Williams, there was no question that she would get the shot. She was rushed to the hospital last November after her blood pressure dropped dramatically; she had been seriously ill for days, unable to even eat.

She had COVID-19.

Not long before that, her mom had also been admitted to the same hospital.

“She was in the hospital first,” Williams recalls. “Her room was 428 and I was 427. She never knew I was over across the room. And so, she had pneumonia of the lungs and COVID. We had the same doctor. [At one point] he asked me to get out the bed. And took my mom to the ICU. I knew then. So, I kissed her [goodbye].”

Seeing the impact of COVID-19 firsthand, Williams says she knew she “had to do something” to stop its spread, and that meant getting vaccinated. As a former Cleveland police officer, she also volunteers to help out with security during Affinity’s vaccine clinics.

Williams’ former partner on the beat, Andre Cisco, a Bedford Heights resident and longtime member of Affinity Church, also got his second shot during that same clinic.

Cisco said he wasn’t really hesitant about getting shot, but he understands why some are.

“A lot of people fear vaccinations because of the Tuskegee Project, so, they’re really not sure,” he says. “(Also) because the vaccine came so fast, so naturally people are going to fear it. It’s not all Black people, either, a lot of young people aren't taking it, either… I think by going to the church, people feel safe, because if they see their pastor do it, and it’s at the church, they think, ‘Oh, it must be okay.’”

Cisco added that it was very convenient to go to a vaccine clinic located “right in the neighborhood.”

Cleveland and Cuyahoga County have similarly tried to locate their large-scale vaccination clinics near where people live. The city has hosted most of its clinics at community centers throughout Cleveland. Meanwhile, the county has mixed in drive-up clinics at its usual site—the Cuyahoga County Fairgrounds—with clinics at fire stations dotted throughout the county, along with several at places of worship like the Word Church in Cleveland and the Islamic Center of Cleveland.

Several volunteers with Cleveland nonprofit Medworks prep vaccine doses at Affinity Missionary Baptist Church during a recent vaccine clinic.But neither Cleveland nor Cuyahoga County is collecting site-specific information on demographics, so it can be hard to know how well those efforts are addressing the racial discrepancies in vaccine administration. Latoya Hunter, a city of Cleveland spokesperson, says the city’s epidemiologist team is working with Case Western Reserve University to start tracking that data, but nothing is ready yet.

Several volunteers with Cleveland nonprofit Medworks prep vaccine doses at Affinity Missionary Baptist Church during a recent vaccine clinic.But neither Cleveland nor Cuyahoga County is collecting site-specific information on demographics, so it can be hard to know how well those efforts are addressing the racial discrepancies in vaccine administration. Latoya Hunter, a city of Cleveland spokesperson, says the city’s epidemiologist team is working with Case Western Reserve University to start tracking that data, but nothing is ready yet.

Kevin Brennan, a Cuyahoga County Board of Health spokesperson, said last month that his agency is keeping an eye on the overall statistics of vaccines administered by race in the county, and is “continuing to search for opportunities” to partner with new locations for vaccine clinics.

Krumm, with Greater Cleveland Congregations, said the vaccine clinics wouldn’t be possible without Cleveland nonprofit Medworks, which works with the churches to stage the actual vaccination events. Meanwhile, the vaccine doses are coming from the city of Cleveland’s supply as well as from local federally qualified health centers.

Jennifer Andress, executive director of Medworks, says the organization is able to bring in a large number of volunteers (many of them doctors, nurses and dentists) to staff the church vaccination sites. They handle all of the patient registration, vaccine preparation and administration of the shots.

“So essentially, we have become a provider arm under the city of Cleveland,” Andress explains. “And then we partner with Greater Cleveland Congregations to identify the locations, and to identify patients to come to the clinics and such. So there, our collective goal is vaccine equity, it’s getting out into neighborhoods that are underserved and being able to bring vaccines closer to them and so that it makes it much more accessible.”

What’s next?

Krumm says her organization has set a goal to fully vaccinate 7,000 Black Cuyahoga County residents before the end of the year. She says she hopes that it could continue to host regular weekly vaccination clinics at one or more churches in the county until they’re no longer needed. She hopes that by having a consistent clinic at a trusted location like a church, week in and week out, people will naturally start to come as they become more comfortable with the idea of the vaccine.

“One of the barriers is just being strategic about where the places are, where we’re getting less people vaccinated and setting up locations there,” she says.

Krumm says she believes many of the people who want the vaccine and are actively seeking it have been able to find it. There are plenty of other people out there who haven’t, though, who either might be “skeptical” or who just have “a lot of pieces in their life to navigate” to figure out how to get an appointment, she says.

Krumm says one good strategy could be asking volunteers to go door-to-door in neighborhoods where the overall vaccination rate is low to ask people if they’d like to get signed up for the vaccine.

GCC is planning on knocking on doors in the Central neighborhood in early May, and urging people to get vaccinated at a clinic at Shiloh Baptist Church. Andress, with Medworks, says her organization will continue to partner with GCC and others to bring the vaccine to parts of the community where vaccinations have been lagging.

What’s next for the people who are now fully vaccinated after going to Affinity Missionary Baptist church?

Williams and Cisco don’t have anything exciting planned on the horizon. Williams, in particular, says she’s still scared of getting COVID-19 again, especially after the tragedy she and her family endured.

“I’m not trying to do anything,” she says. “I get off work and I go home. Latest I’m into the bed is 6:30.”

Johnson is a little more optimistic. She says she’d like to go on bus trips to see other parts of the country, though nothing long-distance for now.

“I’m also involved in a lot of crafts groups and I will be getting back with those,” she says.

This story is sponsored by the Northeast Ohio Solutions Journalism Collaborative, which is composed of 20-plus Northeast Ohio news outlets including FreshWater Cleveland.

Rachel Dissell contributed to this article. You can email Conor Morris at cmorris@advance-ohio.com.