My Brother’s Keeper will build career pathways for region’s marginalized Black youth

This is the latest story in FreshWater Cleveland's series First Suburbs: A Closer Look, focusing on the suburbs surrounding Cleveland. Built mostly before the 1960s, these “first” suburbs face challenges ranging from urban sprawl to disinvestment. But shrinking news coverage reports mostly on crime. This series instead will look at the unheralded people and innovative programs that are making a difference, through a solutions-based journalism lens.

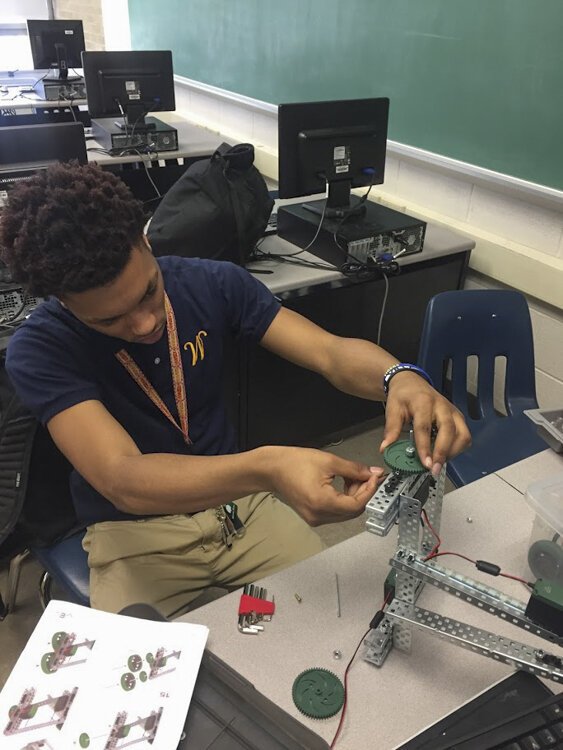

Even before the destructive arrival of COVID-19, boys and young men of color faced opportunity gaps both in the classroom and in workforce development. The pandemic only exacerbated these issues, making the recent launch of My Brother’s Keeper Greater Cleveland Chapter (MBK) an exceptionally vital support.

Launched on Friday, Jan.15 by the Urban League of Greater Cleveland, the initiative delivers mentoring and structured career paths at the high-school level, similar to what Urban League already accomplishes under its Project Ready banner and curriculum. In partnership with the statewide coalition of MBK—launched in 2018 with help from U.S. senator Sherrod Brown—the Urban League will further align its programming to boost the career prospects of target populations.

MBK’s focus area is Cleveland and the inner ring suburban neighborhoods of Cleveland Heights, East Cleveland, Bedford Heights, Maple Heights, and Warrensville Heights.

Starting Point funds the Urban League to provide strong technical assistance to Out of School Time organizations like MyComBy collaborating with two other local efforts—Saving Our Daughters and Students of Promise—underserved Black youth can tap into a web of resources designed to strengthen their careers and higher-ed skill sets. Funding and planning partners for the enterprise include the Cleveland Cavaliers, the Cleveland Foundation, and the Kirwan Institute for the Study of Race and Ethnicity.

Starting Point funds the Urban League to provide strong technical assistance to Out of School Time organizations like MyComBy collaborating with two other local efforts—Saving Our Daughters and Students of Promise—underserved Black youth can tap into a web of resources designed to strengthen their careers and higher-ed skill sets. Funding and planning partners for the enterprise include the Cleveland Cavaliers, the Cleveland Foundation, and the Kirwan Institute for the Study of Race and Ethnicity.

“It was a natural transition to affiliate with MBK, because they have the same initiative of mentoring young people to reach their potential,” says Donald Jolly, superintendent of the Warrensville Heights City School District.

Jolly’s district, like other Cleveland communities connected to the program, is predominately Black, and thus faces specific challenges in linking enrollment to job-ready areas like the trade industry. For example, Black workers comprised only 6% of those employed in construction last year, according to a Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) report.

Lack of job exposure can be attributed to, in part, families passing down trade skills in industries historically unkind to young Black men. This hand-me-down cycle of job readiness is costing marginalized populations potentially lucrative careers.

According to the BLS, the median salary for electricians is $55,190; plumbers, $53,910; and HVACR technicians, $47,610. By 2026, the demand for these jobs is projected to increase by 9%, 16% and 15%, respectively.

Considering the trades are long gone from high-school curricula, MBK’s mission is even more critical, Jolly notes.

“The earlier we can expose young people to these opportunities and the folks doing these jobs, the more they will go into those fields,” says Jolly. “Not everyone is going to college, so the educational system has to provide pathways to students who have other skill sets.”

East Cleveland City Schools superintendent Henry PettigrewGrowing jobs and leaders

East Cleveland City Schools superintendent Henry PettigrewGrowing jobs and leaders

Career-based programs at East Cleveland City Schools never went fully remote during the ongoing pandemic, says superintendent Henry Pettigrew, who points to nursing and auto-tech programs at Shaw High School as just two classes best served by an in-person environment.

East Cleveland has 1,700 students in the district, with 700 learning at Shaw. Career and technical education is crucial for an already-poor community now suffering additional economic insecurity from COVID-19. Luckily, MBK has a long-standing presence in the district thanks to Rev. Stanley Miller, the Cleveland initiative co-chair and former Cleveland NAACP executive director.

While Shaw graduated 84% of its students in 2020—a 5% leap from the previous year—MBK’s umbrella of programming is needed to give Black males hope beyond the abandoned buildings and dilapidated homes they encounter daily.All MBK mentors have master’s degrees in student areas of interest, bolstering those relationships and, ideally, leading to improved outcomes.

“Kids need mentors familiar with their circumstances,” says Pettigrew. “Mentors from MBK respect our students and stretch their imaginations.”

Though college is certainly an option for MBK learners, it’s not a be-all for those desiring a viable skills-based career. Mentors track the Ohio Means Jobs website for employment resources, helping students make clear links between job prospects and educational possibilities.

Urban League CEO and president Marsha Mocakbee“Our students need daily reminders to keep them engaged and moving,” Pettigrew says. “It’s about creating a safe place where students learn about themselves and what they can achieve.”

Urban League CEO and president Marsha Mocakbee“Our students need daily reminders to keep them engaged and moving,” Pettigrew says. “It’s about creating a safe place where students learn about themselves and what they can achieve.”

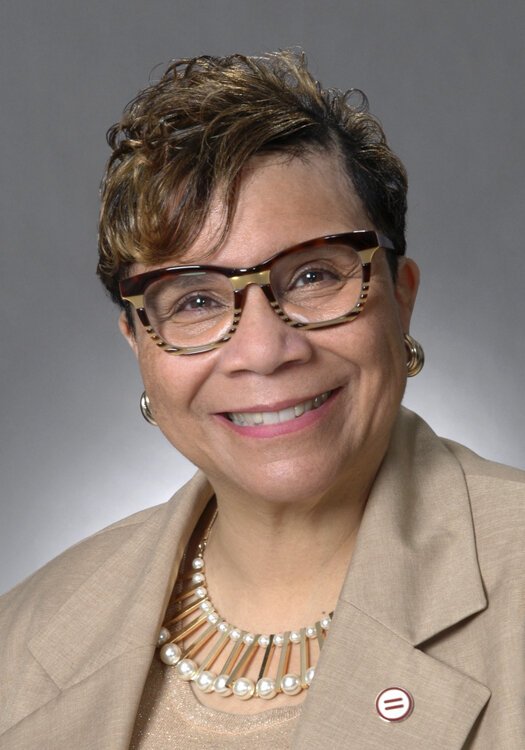

Launched by President Barack Obama’s administration in 2014, MBK has 13 Ohio chapters that provide unique weekly instruction and programming, says Urban League CEO and president Marsha Mocakbee.

The Cleveland chapter’s executive and planning teams spent this month getting set to work on a program plan for all participating schools. Serving between 100 to 150 boys and men is the goal for MBK’s first year, even as the program’s aspirations extend well beyond 2021.

“Through training and schooling, these students should be in a position to learn and earn for the rest of their lives,” says Mockabee. “Our plan is for this group of young men to become our next leaders.”

The series is made possible through the support of Citizens Bank, the First Suburbs Consortium, and the First Ring Schools Collaborative.