Cuyahoga Arts & Culture seeks diversity and equity in next decade

Nick Rabkin has had a long career in the arts—spanning arts practice, arts education, and cultural policy. Based in Chicago, Rabkin has been a consultant and researcher in the cultural sector since 2011. He also acted as the former deputy commissioner of cultural affairs for the City of Chicago, served as senior program officer for the arts at the MacArthur Foundation, and ran the Center for Arts Policy at Columbia College. At both Columbia and the University of Chicago, Rabkin researched arts education and the arts in community life and development.

In light of his background, Cuyahoga Arts and Culture (CAC) commissioned Rabkin in 2011 to co-author The Public Benefits and Value of Arts & Culture: What Have We Learned & Why Does it Matter? as the organization was evaluating its future direction.

Fresh Water: Why is equity an important issue to address in the arts?

Nick Rabkin: Cultural philanthropy and public cultural agencies (like CAC) have, since the late 1800s, focused primarily on building and sustaining cultural institutions. In more recent years, though, some of them have turned their attention to the question of public participation in the arts, and they've found that—by and large—large portions of the public do not benefit much from the programs of many of those organizations.

FW: How do you make sure arts and culture are inclusive?

NR: All kinds of questions about equity in the world of culture have been raised over the last 50 years, as they have in the rest of our society. Who gets to learn art? Who gets to make it and present it? Where? Who gets to enjoy it as an audience? Funders have been a bit slow to address these sticky, complex, and sensitive issues. But that is starting to change, and CAC is one of those public agencies that is in the lead on that.

FW: How did cultural equity become a priority in Chicago?

NR: Chicago did its first cultural plan in 1986 when I was the deputy commissioner under Mayor Harold Washington, Chicago's first black mayor. Mayor Washington was interested in getting resources to neighborhoods that were under-resourced in many, many ways. One of those was cultural.

FW: How does your work in Chicago relate to Cleveland and CAC’s plan?

NR: Like Cleveland, Chicago has an important legacy in cultural organizations, mostly located downtown. We were interested, among other things, in developing cultural resources in those under-resourced neighborhoods—mostly, but not exclusively African-American and Latino—and our planning process was designed to solicit lots of input from them by holding community meetings in every one of Chicago's 50 wards.

FW: How did you get involved in CAC’s plan?

NR: CAC saw the opportunity to reinvest and expand the roles art and culture play in making communities more vital by focusing cultural activity outside of institutions—online, [in] public spaces, and at the community level.

FW: Why did you suggest CAC collect its data via the methods it used—the street team, focus groups, and arts groups?

NR: There are two types of culture opportunities: those that are focused on advancing specific art forms [and] arts infrastructure and those that focus on serving communities through culture. Both are important.

Most advocacy, philanthropy, and public funding of the arts has been in building the country's arts infrastructure. And there’s a lot of arts infrastructure in Cuyahoga County. But we saw just how important is was to get input not only from the arts community, which is always eager to share, but also from the public at large.

FW: Why was it important to place an emphasis on public opinion?

NR: Neither philanthropic monies nor public money has taken the public’s interests into account when it comes to what [types of programming to offer]. We have to pay close attention to the arts infrastructure, but we also want to listen to the people in the country—especially people who may not be participating in the arts.

Northeast Ohio is known around the globe for its rich cultural centers. The Cleveland Orchestra is internationally acclaimed, while Playhouse Square forms the largest theater district outside of New York City. Museums, community theaters, beachfront concerts, dance companies, and more round out the region's wealth of cultural attractions.

Cuyahoga Arts & Culture (CAC) helps ensure the arts continue to thrive in Cuyahoga County through its public funding of non-profit organizations—both large and small—that bring cultural programming to millions of residents each year. Founded in 2007 through a cigarette tax that was overwhelmingly renewed in 2015, CAC is one of the largest public funders of the arts in the United States; to date, the organization has invested more than $158 million in approximately 350 arts groups within its first 10 years.

As CAC enters its second decade, the organization is taking an in-depth look at how it invests nearly $15 million annually to make Cuyahoga County a more vibrant place to work, live, and play.

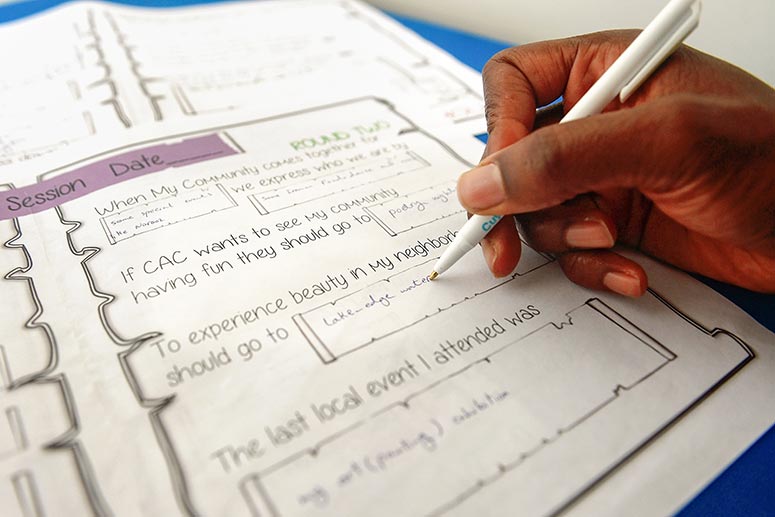

The first step was to undertake an extensive Listening Project in 2016. An 18-member volunteer team hit the streets to ask more than 1,200 people how they get involved in arts and culture, what they would like to see more of, and what CAC was lacking in its programming. CAC also distributed thousands of surveys and assembled focus groups in a diverse mix of neighborhoods and at regional events.

From that outreach came Cuyahoga Voices & Vision, a report on how CAC can best serve the public. Respondents shared their desires for more arts classes and education, more hands-on participatory experiences, and more outdoor cultural activities. Another key finding of the report was that not everyone in Cuyahoga County feels welcome at arts and cultural programming, or they may feel the offerings are not targeted at them.

Fiesta Latina In The Square

Fiesta Latina In The Square

“We heard from many residents who deeply value our community's arts and cultural organizations. At the same time, we heard from folks who said they didn't necessarily feel comfortable at some more traditional cultural institutions,” says Karen Gahl-Mills, CAC's CEO and Executive Director. “We have to look at what’s meaningful in what they’re doing as it pertains to their cultural lives.”

Part of the key will be continuing to engage the public about what it wants and needs—and the organization doesn’t intend to stop listening. “We want to be humble about saying what we don’t know and continue the dialogue with the community,” says Gahl-Mills.

While CAC’s mission—to inspire and strengthen the community by investing in arts and culture—remains the same, the organization has created a new set of values to help support the mission and serve a more diverse group. The listening project's findings are also being used to shape the direction of the next decade, but there is more to learn and more listening to do.

A New Report

Before voters even approved the continued funding in 2015, CAC was already evaluating how its grant recipients generate value for residents and what those residents want in arts and culture.

To that end, the organization recruitedtwo cultural changemakers with proven track records to consult on CAC's future: Holly Sidford and Nick Rabkin. Sidford works with New York-based Helicon Collaborative, an organization dedicated to ensuring improved quality of life through the arts, and Nick Rabkin is a principal with reMaking Culture and a member of the team that created the Chicago Cultural Plan.

Sidford and Rabkin were challenged with answering four questions: How do CAC grantees create public assets, and who benefits? Do the public and the grantees value arts and culture the same? How do policymakers and grant makers understand the public’s value of arts and culture? Can CAC enhance the public’s value of arts and culture?

Together Sidford and Rabkin wrote The Public Benefits and Value of Arts & Culture to outline their observations and recommendations. CAC commissioned the report after a 2011 assessment prompted the organization to adopt a more community-centered mission and shift its funding criteria to focus more on public benefit.

“We have to ensure more people have more access to the public resources they paid for,” explains Gahl-Mills. “We wanted to know what we can do to stay connected to the public.”

Step one: more interactivity. The report stated that while audiences at live performances have been on the decline, demand for events with active participation in the arts is going up. Cuyahoga County institutions are responding to that shift, says Gahl-Mills, with more interactive, maker-centric offerings.

Examples include the Great Lakes Science Center’s Cleveland Creates Zone, where visitors can build and launch a rocket or construct and race a LEGO car; Cleveland Museum of Art’s ArtLens App and monthly MIX at CMA events; or Theater Ninjas’ current staging of “Don't Wander Off,” where audience members participate to choose their own adventures.

But just like shifting audience demands, the audience itself is ever-changing, points out Gahl-Mills. Therefore, CAC’s listening aspect will be ongoing.

Fiesta Latina In The Square

Fiesta Latina In The Square

“The questions ‘What do you do?’ ‘Where do you do it?’ and ‘What do you want to do more of?’ were pivotal in shaping our vision for the future,” Gahl-Mills says. “Because culture is not static, we will continue to find ways to learn from the residents of Cuyahoga County to adapt and respond appropriately to the changing community we serve.”

Equity in Programming

Yet, the report finds there continues to be a racial and economic divide in programming throughout the county. While options have improved in neighborhoods like Collinwood, Gordon Square, and Tremont, gaps persist.

“Many communities and neighborhoods in Cuyahoga County remain under-resourced in terms of arts and cultural organizations and programs,” Sidford and Rabkin stated in the report.

These findings have prompted CAC to place a special emphasis on equity and the awareness that different races and socioeconomic backgrounds can often perceive arts and culture as “not for them” or elitist. “The institutions set up 100 years ago were built in the Western European style of art,” Gahl-Mills points out. “The residents of our community are no longer rooted in only those traditions.”

Racial equity is something that cities all over the country are addressing, as today’s American culture is far more diverse than 100 years ago. CAC is therefore charged with ensuring arts and culture in Cleveland reflects a diverse population. “We have to ask ourselves, 'How do we remain relevant to who we are today?'” Gahl-Mills says. “In Cleveland, you can’t talk about equity without talking about racial equity.”

One example of recent efforts at inclusion is Cleveland Public Theatre’s (CPT) spinoff Teatro Publico de Cleveland (TPC), a Latin American theater ensemble whose work reflects the artistic goals, interests, and ideals of its members. Within CPT’s mission to raise consciousness and nurture compassion through performances and educational programs, TPC shares the diversity and perspectives of Cleveland's Latino culture. Since 2008, CPT has received just over $1 million from CAC through its general operating support program.

Equity in Grants

Along with efforts to attract a more diverse audience, CAC restructured its grant application process to ensure accessibility to a diverse group of arts and culture organizations. CAC deputy director Jill Paulsen says they have an “amazing team” in place to assist applicants—even helping some apply over the phone.

Traditionally, the majority of CAC support has gone to CAC’s general operating support for larger cultural institutions in the community—amounting to about $12 million last year. That support won’t change. However, the group is working to bring more organizations into its project support program, which covers grants of $5,000 to $30,000.

“Over the years, we’ve simplified the application process and provided technical assistance to help organizations,” says Paulsen. “This area of our grant making has grown 300 percent since it started, and we expect the largest number of project support grant recipients this year."

“Over the years, we’ve simplified the application process and provided technical assistance to help organizations,” says Paulsen. “This area of our grant making has grown 300 percent since it started, and we expect the largest number of project support grant recipients this year."

In 2017, more than 220 organizations submitted project support applications—many of whom were new to CAC. According to Paulsen, "38 applicants are new or relatively new, 22 are first time applicants, 12 have applied but were never funded, and four were last funded over five years ago.”

Many of these projects—which include events like festivals and street fairs—are free or low-cost and reach large groups of Cuyahoga County residents and visitors. These events tend to appeal to a wider audience and are often viewed as more accessible than some of the events at more traditional cultural institutions.

New Values

In reflecting on how it can better reach the entire community in Cuyahoga County, CAC defined a new vision along with its original mission: “to inspire and strengthen the community by investing in arts and culture.”

With that vision comes a refreshed set of values reflecting both CAC’s mission and vision: Connection, Discovery, Equity, Service, Stewardship, and Trust. These values form the core of CAC’s action plan as it moves forward in 2018.

“Naming those values has given us an extra push to see how we can be accessible to the public,” says Gahl-Mills. “We want to see how we can best support meaningful cultural life for all Cuyahoga County residents.”

The equity issue doesn’t solely exist in Cleveland, though, and it’s an issue that must be addressed across the board, says Gahl-Mills. “What we have done—and what’s going on nationally—is [to] have a conversation about equity in arts and culture,” she says. “Every agency is thinking about this question.”

Sidford and Rabkin addressed this question as it pertains to the Cleveland region. As stated in their report, “The viability of many cultural organizations will depend on serving more diverse parts of the community, with dynamic, relevant programming that is as much about enabling people to make art themselves as it is about improving the audience experience.

Looking Beyond Cleveland for Inspiration

Much of the listening work CAC embarked on was inspired by the Brooklyn Insights project, a 2014 undertaking by the Brooklyn Community Foundation to achieve many of the same goals as CAC—to spark social change through developing new grant making and leadership approaches.

“We had 20 to 25 forums to discuss the major issues, extemporary projects, and what the major changes would be if things would be different,” explains Sidford, who also consulted on the Brooklyn project. “Out of all of our conversations, the youth in Brooklyn, gentrification, and the effect on kids [were focus areas that] came out. Out of that came some changes at the Brooklyn Community Foundation.”

Sidford sees the parallels between what Brooklyn did and what Cleveland is attempting through CAC. “Parts of Cleveland are not so different than parts of Brooklyn in terms of access to resources and decision-making,” she says.

Similar to Brooklyn, Paulsen notes that common barriers also exist in preventing participation. “Accessibility is about cost,” she says. “It’s also about access via transportation. And it’s also about supporting a variety of arts and culture events and organizations that appeal to all county residents—and making sure people know those events exist.

CMA Chalk Festival

CMA Chalk Festival

More than half of the thousands of CAC-sponsored events last year were free, such as the Star Spangled Spectacular and Arts & Culture in the Square (thanks to a grant from the National Endowment for the Arts). However, efforts to spread the word about these events need to be improved, says Paulsen. Gahl-Mills reports that many residents say they don’t find out about events until after they have occurred.

While CAC regularly sends out email newsletters to more than 10,000 people and provides a searchable events guide on its site, the organization is aware that not everyone has immediate access to the Internet. To reach additional audiences, CAC has started to distribute event information and calendars to various locations throughout the county, like libraries and coffee shops. Leaders are considering various ways to spread the word via television and radio as well.

Moving Forward with a Plan

The Listening Project and the Public Benefits report offered a lot of insight into determining CAC's priorities in its next decade, and the CAC board approved the Cuyahoga Voices and Vision plan and roadmap in December 2016.

Looking ahead, CAC leaders plan to continue their exploration of how to equitably support the county’s mixed and vast cultural offerings. They also plan to continue working with residents to experiment and explore effective options that serve everyone.

That work will take time, says Gahl-Mills. She says CAC will test communications strategies to find what works, assess underserved neighborhoods to determine how to provide better support, and pilot projects and learning opportunities to create the right programs.

The resources to accomplish this have already been budgeted. Gahl-Mills says CAC should be ready to implement new initiatives based on what they learn by mid-2018.

“We shouldn’t be complacent in doing what we’re doing,” Gahl-Mills says.

Like the rest of the CAC team, Paulsen believes that arts and culture has the potential to be much more powerful than just an enrichment tool. “The arts are powerful,” she says. “By paying attention to issues of equity and sparking connections, the arts can be a vehicle of change.”

Support for the Art. Culture.Connection. series is provided by Cuyahoga Arts & Culture.