local innovators in the spotlight at cleveland clinic medical innovation summit

Often called the premier healthcare gathering in the country, the Cleveland Clinic’s 12th annual Medical Innovation Summit takes place at the Cleveland Convention Center beginning Monday, October 27th through Wednesday, October 29th.

More than 1,500 of the country's top medical innovators will descend on Cleveland to discuss and debate topics around this year’s theme: Now it’s Personal: Cancer and Personalized Medicine. The event is jam-packed with fascinating topics such as cancer approaches around the world. Fresh Water sought out four of Cleveland’s top innovators who are speaking at the summit.

Gary Fingerhut, executive director of Cleveland Clinic Innovations

Cleveland Clinic Innovations (CCI) is the commercialization arm of Cleveland Clinic. CCI turns the breakthrough inventions of Cleveland Clinic employees into patient-benefiting medical products.

Since its formation in 2000, 66 companies have been enabled by Cleveland Clinic technology and expertise. Nearly three-quarters of these companies have received over $750 million in equity investment to date. CCI has transacted nearly 450 licenses and has more than 2,200 patent applications, with 525 issued patents.

“We are very much focused on making a difference in patients’ lives by transitioning all innovations we’re bringing to healthcare,” says Fingerhut. “We’ve created over 1,200 jobs and we’re taking technology to the world to improve patients’ lives.”

At the summit, Fingerhut is sitting on a panel titled “Developing, Building, and Sustaining an Innovative Culture.” The group will discuss establishing an innovation culture in both an academic medical center and community hospital setting.

Fingerhut also moderates two panels at this year's summit. The first, “Innovestment: The Trends and Issues with Crowdfunding and Crowdsourcing,” looks at how these trends apply to medical innovation. The second, “Health IT: How Data Can Personalize Healthcare,” describes how organizations are turning genomic data into useable information about diseases, patients, and treatments.

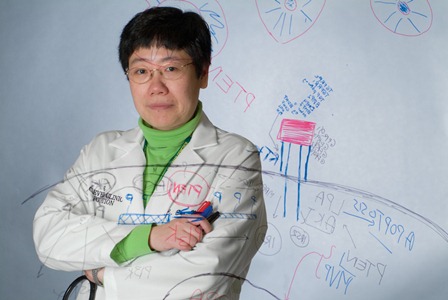

Charis Eng, chair of Cleveland Clinic’s Genomic Medicine Institute

Ten percent of all diseases have an underlying genetic cause, from heart disease to cancer. Charis Eng, a leader in cancer genetics, is quick to say genetic testing for cancers that run in your family is not a fishing expedition to find some potentially bad news, but rather a good way to stay educated and prepared.

“You can start screening early before the risk becomes too high,” she says. “If knowledge is power, then we know how to screen.”

In the panel discussion “The Business of Cancer Risks: You're Well Now. Are You Going to Get Sick?” Eng will discuss genetic testing that looks for specific inherited changes in a person's chromosomes, genes or proteins. The panel will debate who should consider genetic testing for cancer risk, how genetic testing is done, and what the results of genetic testing really mean.

Eng recommends testing only after getting genetics evaluation from a genetics professional. If testing is recommended, a genetics counselor will guide a patient through the process. So who should consider genetic testing for cancer? The red flags that clue us in include young age of onset of the cancer; guilt by association; familial clustering of cancers; bilateral cancer in paired organs; or multifocal cancers.

Genetics counseling doesn’t have to be scary. Rather, a counselor can guide patients through the screening options, including taking a family history of diseases that run in the family. Counselors can also prep patients for the test – what to expect, what the test is like and what comes next based on results. Finally, they know the latest research and can guide patients through different options.

Detailed family histories are particularly helpful in genetic testing for cancer, Eng stresses. “A family history is a wonderful tool in genetic testing,” she says. “It’s like family triage.”

While genetic testing has been around for a while, Eng marvels at how far it has come and the promise it holds today in finding and treating genetic diseases early. She compares genetic testing today to reading a set of encyclopedias.

“The first genetic testing utilized cytogenetics -- spreading the chromosomes to look for large defects,” Eng explains. ”We have 30,000 genes, or encyclopedias, residing on 46 chromosomes, or bookshelves. Cytogenetics or the karyotype allows one to see the 46 bookshelves. If many encyclopedias are missing or a large chunk of the bookshelf is gone, then it is detectable."

Continuing the metaphor, Eng stresses how sophisticated the technology has become. "Only recently, we could read one encyclopedia at a time to look for typographical errors -- mutations and alterations," she says. "In the last year to three years, we are able to very quickly read all 30,000 genes at once to find that one fatal typographical error.”

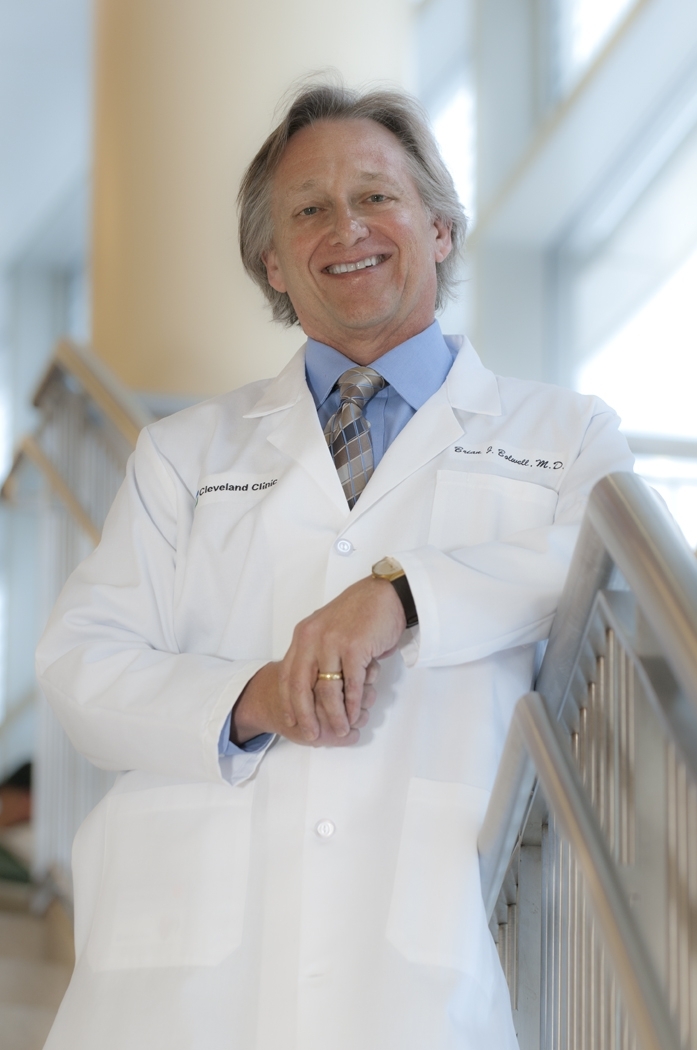

Brian Bolwell, chair of the Cleveland Clinic Taussig Cancer Center Institute

Similarly, Brian Bolwell looks at what medical professionals should do with the wealth of information available about cancer today. “The way we approach cancer has changed pretty dramatically in the last 10 years,” he says. “What can we do if you’re trying to change the way to treat people and change a culture?”

Bolwell, who will sit on the panel discussion, “Personalized Medicine Today: You Have Cancer. Now What?” expects a lively discussion on the ethics and practices involved in personalized care. “How much should we test and what can we find out before we get a cancer diagnosis,” he asks. “Can we predict cancer, and can we do something about it? It’s very controversial.”

Bolwell explains that every cancer is associated with a genetic abnormality. The dilemma becomes a question of what and how much can be done about it, especially with the already-high costs of healthcare. “It’s the role of value-based healthcare – we’re going to be managing populations,” he says. “From a societal perspective, there’s no easy answer.”

Bolwell, along with Taussig colleague Brian Rini will share the many challenges in current cancer research as well as new ideas and innovations that are improving cancer therapy and delivery of care.

Pete Buca, vice president of technology and Innovation at Parker Hannifin

What do a leader in healthcare innovation and the leader in motion and control technology have in common? Actually, quite a bit. In 2007, the Cleveland Clinic and Parker Hannifin formed a partnership to solve complex healthcare challenges with innovative medical devices that can improve patient care and safety.

The Parker team regularly consults with a national network of doctors, shadows live surgeries and participates in ongoing brainstorms to enhance existing devices and introduce new products to the market. The partnership has developed some promising technology. “It’s a really great relationship,” says Pete Buca, vice president of technology and innovation at Parker. “The Clinic taught us about life sciences and we taught the Clinic about technologies.”

Buca will participate in a panel on “Value-Based Innovation,” discussing innovation’s role in delivering solutions to healthcare challenges.

With more than 100 devices in the pipeline, five products are currently in the feasibility stage of manufacturing, with two approaching commercialization as early as next year.

The first product approaching commercialization is an endoscopic sheath that protects patients from infection during intubation. “The Clinic needed a sheath to protect the intubation device and protect the patient from infection,” explains Buca. “Parker focuses on observing how users and customers use the products. The Clinic invited us to observe along with them.” The observations led to the development of the sheath. It’s due to be released in Europe next year.

Parker also developed the Navis Torquer, a device used in carrying wires to the heart during procedures such as angioplasty, by designing a product that is easier to manipulate. Ten million cardiac procedures are done each year and use two to four torquers at a time. Doctors use the torquer to manipulate and push the wires through the artery. But if the torquer has to be changed, the wires would have to be pulled out and the process started again.

“We developed a side torquer,” says Buca. “It’s loaded from the side, instead of taking the wire out. We made it triangular, instead of square, for easier manipulation. We took the basic design and improved it, created a prototype out of plastic and tested it around Ohio. This procedure is done so often in the U.S. and around the world. It’s great for the patient.”

Cell-X, a product developed jointly between the two organizations, came out of a need the Clinic had and a technology Parker possessed. “The Clinic was working on developing a method in which a computer could decide what cells it picked up, but they didn’t know how to pick up the exact cells and move them somewhere else,” explains Buca. “Parker had the opposite technology – using syringes to deliver and precisely locate a micro-cell in space and drawing liquid into syringes.”

Cell-X harvests cells and concentrates them for cell therapies, such as in heart cell therapy. The product has been tested and is close to commercialization.

Check out the top 10 medical innovations announced at the summit here.