Commercial restoration: How investors and CDCs encourage reuse of historical structures

Although it has sat vacant for a few years, the former Lorraine Medical Supply building is in the early stages of restoration by local investor and business owner Eugene Pallas. Located on the northwest corner of West 65th Street and Lorain Avenue in the Detroit Shoreway neighborhood, the white terracotta commercial building was constructed in 1924.

Pallas says he also expects to begin exterior restoration work this spring when he finishes renovations at nearby Lorain Furniture & Appliances, which he also owns.

“Emotionally, I think it's fulfilling for a neighborhood to see a space that was underutilized become a part of the neighborhood fabric again,” says Jessica Trivisonno, economic development director for the Detroit-Shoreway Community Development Organization (DSCDO).

Exterior shot of the former Lorraine Medical Supply Building, which stands at the corner of Lorain Avenue and West 65th.DSCDO has facilitated recent conversations about the construction of an additional shared parking lot for Pallas’ project and a nearby ministry. DSCDO also helps would-be tenants find commercial space in the neighborhood—something Trivisonno says she is open to doing for Pallas, once the project is complete.

Exterior shot of the former Lorraine Medical Supply Building, which stands at the corner of Lorain Avenue and West 65th.DSCDO has facilitated recent conversations about the construction of an additional shared parking lot for Pallas’ project and a nearby ministry. DSCDO also helps would-be tenants find commercial space in the neighborhood—something Trivisonno says she is open to doing for Pallas, once the project is complete.

Pallas, who grew up on the west side, bought the Lorraine Medical property at 6500 Lorain Ave. in 2019. It was originally a Rexall Drug Store and served as various medical offices throughout its nearly 100-year history. Pallas says a previous owner told him that one office was rented by a doctor and alleged serial killer during the ‘30s, though he hasn’t been able to confirm that rumor.

The property was kept in good enough condition that Pallas considered it an attractive buy and a “blessing”—the building is at a prominent intersection, the roof is less than five years old, and the potential for productive reuse is great.

However, any unforeseen costs can set a restoration project back a significant sum of money. For example, Pallas had to invest in replacing the building’s boiler. When finished, the property is expected to be used in a similar fashion to its original purpose, with five retail spaces on the ground level and eight or so offices on the second floor.

Cleveland has lost much of its historic architecture, but mixed-use buildings that remain can help revitalize neighborhoods and encourage economic vitality. Whether public or private, restoration projects across the city are useful tools for community development.

In fact, Community Development Corporations (CDC) across Greater Cleveland make it a priority to support projects that preserve and maintain the historic buildings and architecture that make up the fabric of the neighborhoods they serve.

“In a lot of ways, it feels more organic and grassroots to see a building rehabilitated as opposed to new construction,” Trivisonno says. “And a project like Eugene's is a perfect example of how uplifting that can be—a longtime local business owner who has proven their commitment to the neighborhood is bringing new life to a gorgeous building on a key, commercial intersection.”

Historic Variety Theatre‘We have to try to save it.’

Historic Variety Theatre‘We have to try to save it.’

That motivation also holds true with Burten, Bell, Carr Development (BBC). The CDC has preliminary plans for reuse of the 1928 Moreland Theater, 11820 Buckeye Road in the Buckeye neighborhood, but the organization will need some assistance to bring the property back to life.

“A project like Moreland gives me pause because it is so daunting, but it’s in such a key area on Buckeye Road that we have to try to save it,” says Joy Johnson, BBC executive director. “It’s a comprehensive approach that involves building on existing assets.”

BBC, which serves the Central, Kinsman, and Buckeye neighborhoods, acquired the theater in 2019. The organization received a grant to stabilize the structure from Cleveland Mayor Frank Jackson’s Neighborhood Transformation Initiative Fund, but will need additional investment to carry out its vision of a space for startup businesses on the ground floor and either residential or office space on the second floor.

It’s the type of mixed-use reinvestment BBC encourages across its footprint and can help bring new small businesses into Cleveland neighborhoods.

Proof that such a restoration can work sits just across the street from Moreland Theater at Providence House’s second Cleveland campus, which is located in a grand, former bank known as the Weizer Building. It was built in 1924 with Beaux-Arts style architecture and is listed on the Ohio National Register of Historic Places (NRHP). In 2019, the building received a $3 million dollar renovation and conversion to Providence House's crisis center.

Many of the structures on Cleveland’s east side have been demolished—some during urban renewal and federal highway construction that occurred throughout the ‘50s and ‘60s. Additionally, redlining by banking institutions made it more difficult for Black shopkeepers and property owners in east side neighborhoods to apply for fair loans.

Historic Variety TheatreSome buildings have been vacant so long that restoring them is no longer financially feasible, and the structural integrity of the buildings pose public safety risks.

Historic Variety TheatreSome buildings have been vacant so long that restoring them is no longer financially feasible, and the structural integrity of the buildings pose public safety risks.

Those losses make the remaining buildings in these neighborhoods all the more special, and restorations can help residents and investors regain confidence in the neighborhood while creating placemaking opportunities and improving citizen involvement in neighborhood affairs.

“Consistently, rehabilitation promotes heritage tourism, more new jobs than new construction, attracts more small businesses, and is environmentally responsible,” says Margaret Lann of Cleveland Restoration Society, citing a 2020 study by Place Economics titled, “Twenty Four Reasons Historic Preservation is Good for Your Community.”

Benefits of mixed-use restorations

CDC officials’ desire for their neighborhoods to include varied buildings is similar to an argument author Jane Jacobs made in her 1961 book on city planning, “The Death and Life of American Cities."

“Mixed-use buildings were thought of as ugly and chaotic—but new ideas require old buildings, and creates, at the worst, a merely interesting place and, at the best, a delightful place to be,” Jacobs writes.

To Jacobs, a mix of uses, building types, and diversity on a street can make people want to do everything from walk the neighborhood to open a business.

Over time, that blend and infusion of activity can lead to self-sufficient economies and natural regeneration in cities. Projects like Pallas’ Lorraine Medical Building in Detroit-Shoreway and the Moreland Theater renovation BBC envisions in the future show that a building is not limited by its architecture to one specific use.

“There has always been a desire in the community to see [Moreland Theater] preserved and restored, and it is important to make an effort when there is so much sentimental value,” BBC’s Johnson says.

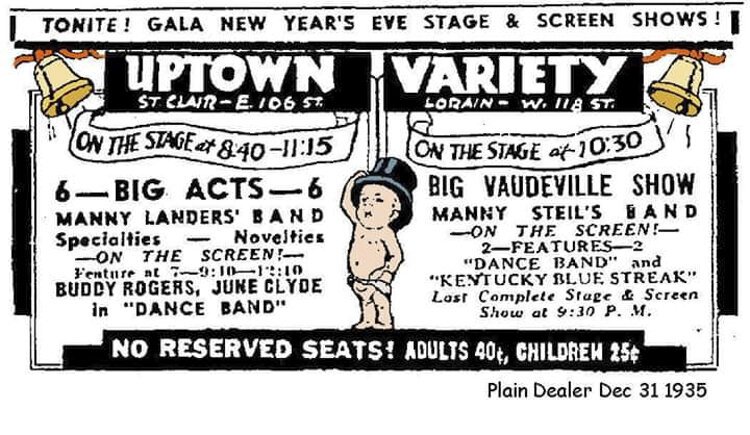

Moreland Theater opened in 1928 as a vaudeville theater that also played silent movies. It is one of the few remaining large-scale theaters of its kind left and is one of five theaters in Ohio constructed by architectural firm Braverman and Havermaet for real estate developer A.T. (Adolph) Wallach. The building has historical significance, initially serving Cleveland’s immigrant Hungarian community. It was added to the NRHP in 2011.

Historic Variety TheatreWhen the Great Depression hit in 1929, many theaters closed and the demand for these shows dropped significantly. Moreland lasted until the ‘50s and was used as a nightclub and music performance theater up until the ‘70s, according to the NRHP nomination form.

Historic Variety TheatreWhen the Great Depression hit in 1929, many theaters closed and the demand for these shows dropped significantly. Moreland lasted until the ‘50s and was used as a nightclub and music performance theater up until the ‘70s, according to the NRHP nomination form.

Finally, the building served as home to various churches until it was abandoned entirely around 2012.

About three years later, local residents and artists created public art panels along the building to improve its appearance and further cultivate community.

In a similar situation, The Variety Theatre on Cleveland’s west side has plans in place for restoration, but they are far from complete. In 2006, a nonprofit, Friends of The Variety Theatre was formed to aid in restoration. Projects like Moreland and Variety require dedicated people and resources to preserve and rehabilitate these large buildings back to productive use. However, there are many different paths that nonprofits and investors can employ during the process.

“Nonprofits such as Cleveland Restoration Society and Heritage Ohio are great resources, as is the Ohio Historic Preservation Office and Ohio History Connection,” Lann says. “[State and federal] historic tax credits can be great incentives for income-producing restorations of commercial structures. Cleveland has some of the highest use of historic tax credits by developers in the state of Ohio.”

The various incentives available to those willing to invest in old buildings, instead of demolition or new construction, make these projects much more feasible than if a private or public entity were to attempt restoration alone. With the availability of those resources and the proven benefits of restoration as opposed to demolition, Cleveland has a chance to be a leader in adaptive reuse projects with its existing building stock.

Still, public-private partnerships, committed local investors, local organizations, and caring residents all play an integral part in the preservation efforts of structures with architectural value.

“It's like lasagna—different grants are layered on top of one another to acquire the money needed to bring [Moreland] back to life,” Johnson says. “As a nonprofit, we can apply for various grants at the state and federal level, but there needs to be a proven track record of capability to bring the project together.”

This story is part of FreshWater’s series, Community Development Connection, in partnership with Cleveland Neighborhood Progress and Cleveland Development Advisors and funded in-part by a Google Grant. The series seeks to raise awareness about the work of 29 Community Development Corporations (CDCs) as well as explore the efforts of neighborhood-based organizations, leaders, and residents who are focused on moving their communities forward during a time of unprecedented challenge.

About the Author: Nate J. Lull

Nate J. Lull is currently studying regional planning at Cleveland State University Levin College of Urban Affairs, the number two ranked urban policy school in the country, seeking his bachelor's degree. In his spare time, he works as a computer technician and volunteers locally. He has also done work for Documenters.org, a civic-led initiative aiming to promote transparency and accountability of local government.